Brought to you by SCARPA

Avalanches are not a force to be reckoned with. However, with proper backcountry habits, avalanche risk can be minimized.

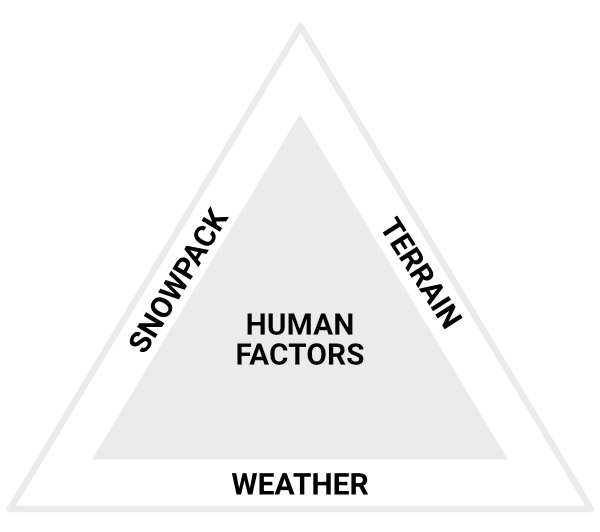

The diagram below is known as the avalanche triangle. To trigger an avalanche, you need all three things. The snowpack needs to be unstable and the location needs to be on avalanche terrain. Weather and snowpack are outside of our control, but the terrain is static and completely in our hands. By selecting non-avalanche terrain, we can minimize our risk of triggering an avalanche.

“If avalanches are the problem, terrain selection is the solution.”

– Steve Reynaud, Sierra Avalanche Forecaster

What constitutes avalanche terrain?

Slope Angle

Avalanches usually occur on 30 to 45-degree slopes. If a slope is less than 30 degrees, it is hard for gravity to pull the snow enough to put a serious strain on the snowpack. If the slope is over 45 degrees, it is hard for the slope to hold snow well enough to develop avalanche problems. Just because most avalanches occur between these angles, skiers should continue to be alert to avalanche risks on slopes that are steeper or shallower.

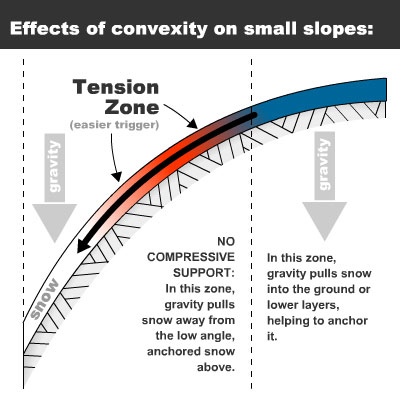

Convex Rolls

Convex rolls create prime avalanche terrain. The gravity pulls the snow downhill towards the bottom of the hill and the gravity pulls the snow onto the ground on the top. Between these two zones, there is a point of high tension that makes it very easy for avalanches to be triggered. When traveling in the backcountry, it is a good idea to avoid convex rolls.

Vegetation Clues

Vegetation clues can be your best friend out in the backcountry. Some examples of vegetation clues include flagged trees, new vegetation, snapped trees, or no trees at all.

Flagged Trees

As you can see in the image above, these trees have had their uphill branches ripped off by the force of avalanches. These are known as “flagged trees” and can be signs of previous avalanches and can mean that the area is avalanche terrain.

Young Trees

New vegetation can signify that an avalanche has recently come through the area and might be avalanche prone, hinting that it is avalanche terrain.

Snapped or Broken Trees

Snapped or broken trees can signify that an avalanche has recently come through the area and might be avalanche prone, signaling that it is avalanche terrain.

Lack of Trees

Lack of trees can be one of the most telling signs of a defined avalanche path. Lack of trees usually means that avalanches come through the area quite frequently, so they should be avoided when traveling in the backcountry.

Consequences and Terrain Traps

Consequences are very important to keep in mind when skiing in potential avalanche terrain. If a line is of high consequence, it is avalanche terrain and should be skied with caution or not skied at all. Below are a few examples of high consequence terrain.

A terrain trap is a line or area where consequences are particularly high.

Cliffs

Cliffs are a perfect example of high consequence avalanche terrain. If an avalanche were to trigger above cliffs, it could sweep you over and worsen your injuries and increase your chance of death.

Trees

Trees at the end of runs can be hazardous because if there were an avalanche, the avalanche would carry you directly into the trees, slamming you into them with tremendous force and increasing your chance of fatality.

Chutes and Gullies

Slopes that have chutes and gullies should automatically be a red flag. If an avalanche were to trigger in a chute or gully the force is directed into a smaller space, making it faster and more dangerous. In a gully, all of the snow will settle in the bottom, potentially allowing the skier to be buried under more snow. These are considered to be terrain traps.

Crevasses

Slopes riddled with crevasses can be especially deadly due to the difficulty of spotting them. Crevasses can be covered over the top with snow, which could give at any moment and allow an unsuspecting skier to fall through. Crevasses are commonly found on glaciers or steep slopes that have been subjected to an intense melting cycle. Small and visible crevasses after a period of warm temperatures can also be a warning sign of a glide avalanche.

Trigger Points

Trigger points can be especially dangerous and unpredictable in the backcountry. A trigger point is a point where the stress on the snowpack is greater than other areas, meaning even the smallest amount of pressure can trigger an avalanche. Trigger points are commonly created by three things.

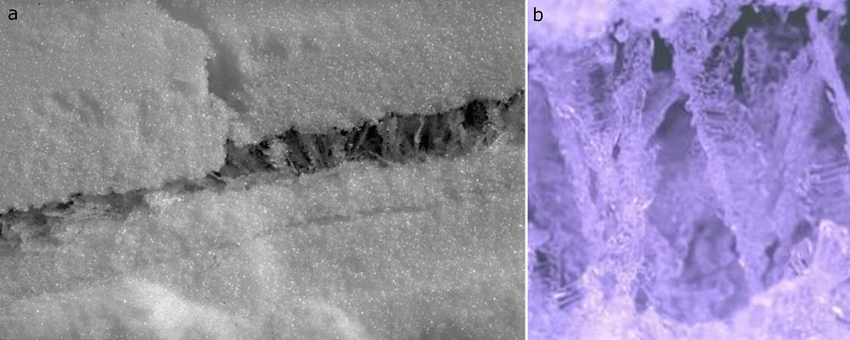

#1: The Weak Layer is Especially Weak

If the buried weak layer is especially weak, it becomes much easier to trigger by a skier because it has a lower pressure tolerance before sliding.

#2: The Stress on the Weak Layer is Especially Large

If the stress on the weak layer is especially large, the amount of pressure needed to trigger it becomes dangerously low. This can be created by large or heavy amounts of snow on top of the weak layer, a convex slope, or a steep slope.

#3: The Slab on Top of the Weak Layer Is Especially Thin

If the slab on top of the weak layer is especially thin, the amount of pressure needed to penetrate deep enough in the snowpack to trigger the weak layer is lowered significantly. This makes avalanches much easier to trigger and is usually more dangerous than the other two reasons. Since low levels of snowfall on top of weak layers are usually region-wide, while the other two reasons can be very localized and specific to certain terrain features (steep slopes, convex slopes, etc), this reason is slightly easier to predict if you know all of the layers in the snowpack. Sun, rain, and wind, however, can change the snowpack on certain aspects so it is important to keep in mind that the snowpack can be localized but is generally similar within an area. So if there is not a lot of snow on top of a weak layer, it will likely be an avalanche problem across all-terrain features and aspects.

How can I take what I just learned and apply it to my backcountry skiing?

The three main factors that contribute to avalanche risk are unstable snowpack, a trigger, and avalanche terrain. Snowpack is out of our control; the weather patterns of the season have already decided the stability of the snowpack. If you are skiing a slope, you automatically have a potential trigger. The one aspect of avalanche risk in our control is terrain selection. To trigger an avalanche you need all three aspects of avalanche risk. By using the aspect that is in our control to our advantage, we can maximize the mitigation of avalanche risk. You can do this by identifying avalanche terrain and avoiding it while skiing.