This weekend, the Colorado Avalanche Information Center released its full report from the fatal slide near Winter Park Resort, CO, on January 7th, 2023. The findings can be a learning opportunity for all of us.

The full report is below:

Avalanche Details

|

Number

|

Avalanche

|

Site

|

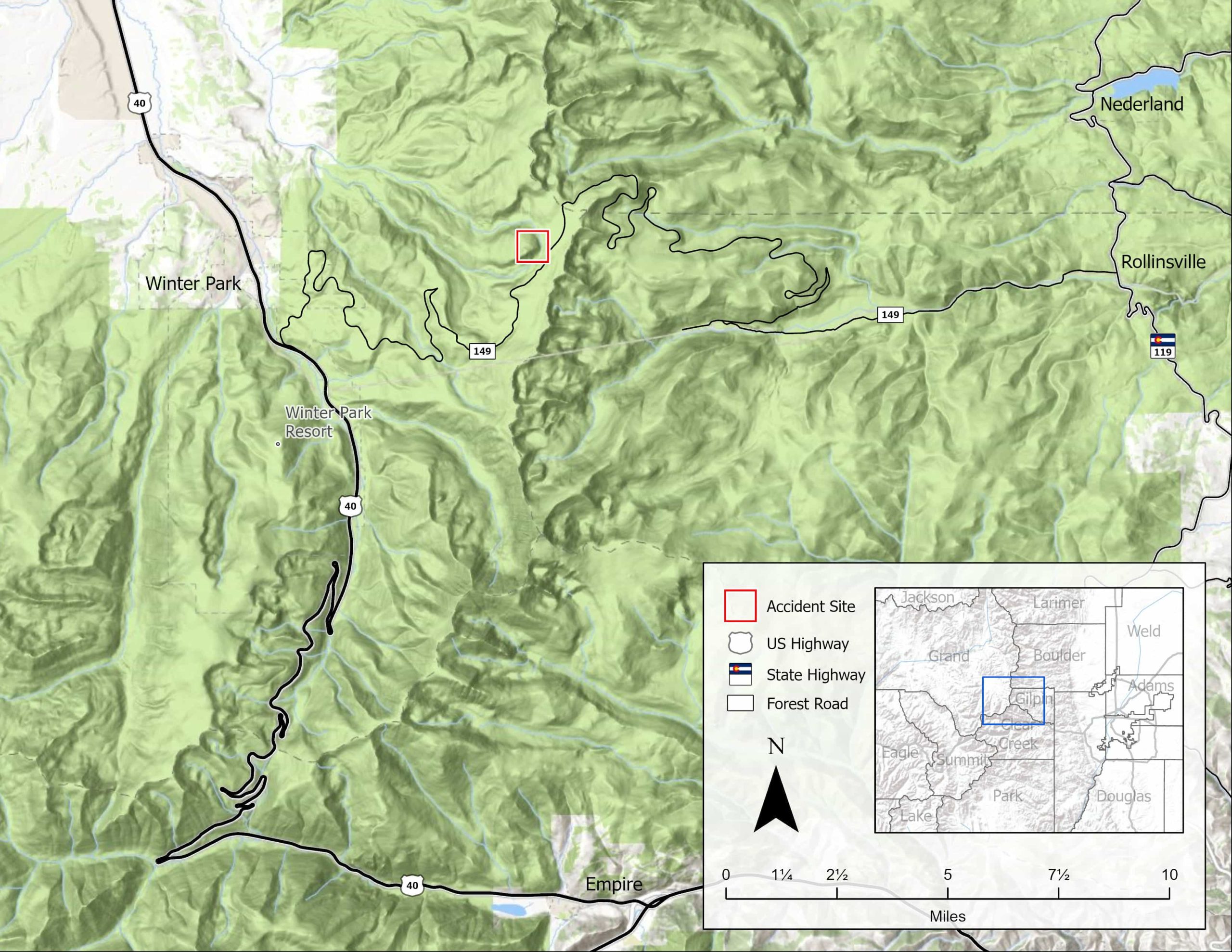

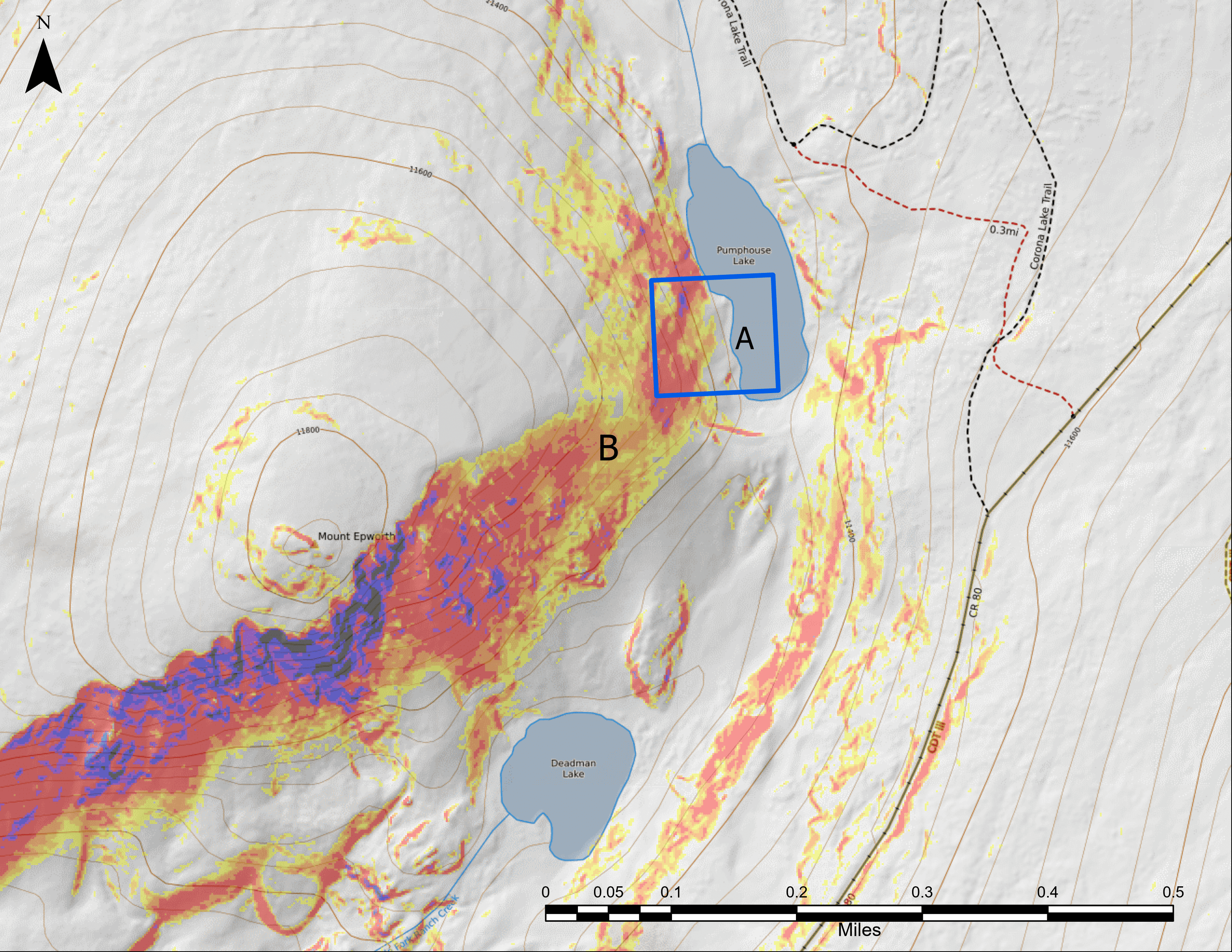

Avalanche Comments

The avalanche occurred on an above-treeline, east-facing slope on Mount Epworth above Pumphouse Lake, three-quarters of a mile southwest of Rollins Pass. It was a large avalanche unintentionally triggered by a snowmobiler. It was medium-sized relative to the path and produced enough destructive force to bury, injure, or kill a person. The avalanche broke on a layer of faceted crystals near the ground (HS-AMu-R3-D2-O). Westerly winds drifted large amounts of snow onto the slope where the avalanche started. The avalanche ran into Pumphouse Lake, breaking the lake ice and exposing water in places. The avalanche broke approximately 5 feet deep and about 400 feet wide. It ran 175 vertical feet. Another large avalanche released sympathetically on the southeast face of Mount Epworth above Deadman Lake (HS-AMy-R2-D2).

Backcountry Avalanche Forecast

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center’s (CAIC) forecast on January 9 rated the avalanche danger at CONSIDERABLE (Level 3 of 5) at all elevations. Persistent Slab avalanches with a likelihood of Likely were highlighted on all elevations on northwest through northeast to south-facing slopes. The expected avalanche size was Small to Large (up to D2). The summary stated:

You can trigger a large, deadly avalanche on northwest through east to south-facing steep slopes. You are most likely to trigger an avalanche from an area of shallower snow and it may break near the ground on weak layers buried one to three feet deep. You can trigger these avalanches from the bottom of a slope or from a distance and they can break wider or run farther than you anticipate. Be cautious of wind-drifted slopes that face any direction, but especially easterly-facing slopes below ridgelines, downhill of convex rollovers, and in gully features. Any steep slope with smooth, bulbous pillows of snow above weak snow at the ground is suspect; a small avalanche can easily trigger a larger more deadly slide. If you see signs of unstable snow like cracking or collapsing, move to slopes less than about 30 degrees that are not connected to larger, steeper slopes above.

Weather Summary

The seasonal snowpack began accumulating in late October. Small early-season storms were interspersed by dry periods with mild days and cold nights. Snowfall became more consistent in late November as frequent storms moved through the Front Range. On December 27, there was a shift in the weather pattern as the first in a series of moist Pacific storms moved through Colorado. The sustained stormy period lasted through the first week of January.

On January 7, Winter Park ski area, approximately 5 miles west of the accident site, reported 5 inches of new snow in the last 24 hours. Northwest winds were gusting over 30 mph and drifting snow at ridgetops. At 1:45 PM, observers near the accident site recorded overcast skies, no precipitation, an air temperature of 16 degrees Fahrenheit, and light westerly winds.

Snowpack Summary

The early season snowpack remained shallow through most of November. By November 26, the 30 to 45 cm (12 to 18-inch) deep snowpack consisted of faceted snow, a weak base for future snowfall. The faceted layers were buried on November 26.

Consistent snowfall in December, with several wind events and periods of warm temperatures, formed a cohesive slab of snow above the faceted basal layers. Wind drifting added additional snow resulting in a slab over 5 feet thick on the slope that avalanched.

Events Leading to the Avalanche

Three snowmobilers left the Lakota trailhead south of the town of Winter Park on the morning of January 7. They were headed out for a day of riding in the Rollins Pass area. Rider 1 had ridden in the area many times. Riders 1 and 3 wore avalanche transceivers. Rider 2 did not. All of the riders had shovels but only Rider 1 had an avalanche probe pole. The three riders did not discuss avalanche conditions and were unaware of the avalanche danger rating.

They rode into the area southwest of Rollins Pass. Rider 1 was snowmobiling on the east-facing slope above Pumphouse Lake and got stuck. Rider 2 rode onto the slope to help. After three or four tries, he was able to park his snowmobile just to the north of Rider 1. Rider 3 waited below, at the lake.

Accident Summary

Rider 2 got off his snowmobile and was walking toward Rider 1 when the avalanche released. Rider 3 watched the avalanche hit his friends. They disappeared in the moving debris.

Rescue Summary

Rider 3 searched the avalanche debris looking for his friends. He found part of the skis from each snowmobile sticking out of the snow, but no signs of his friends. He tried searching with his avalanche transceiver, but was unsuccessful.

Rider 3 rode to a nearby ridge to get phone reception. He called 911 at 2:14 PM. The 911 dispatcher initiated a response and had a member of Grand County Search and Rescue (GCSAR) call Rider 3. GCSAR told Rider 3 that it would take at least an hour for them to get to the scene and that he needed to return to the avalanche to search for his friends. Rider 3 described his initial rescue effort and the GCSAR member explained basic search tactics to him. Rider 3 returned to the scene to continue the search.

Rider 3 struggled to use his transceiver and abandoned the transceiver search. He took out his shovel and dug around the buried snowmobiles trying to find his friends. While he was digging he stepped into slushy snow, where lake water was mixing with the snow, and his leg got stuck.

Around 2:45 PM a group of nine snowmobilers participating in an avalanche course were riding through the area and saw the recent avalanche and Rider 3 standing in avalanche debris. They rode over to see if he needed help. Rider 3 told them his two friends were buried. The avalanche course instructors organized a search. The group helped Rider 3 turn off his transmitting avalanche rescue-transceiver and free his leg from the slush.

About half of the avalanche class searched with their transceivers for Rider 1. Within a few minutes, they pinpointed a signal with a very low distance reading and began digging. They found Rider 1 under two to three feet of debris. He was face down in the lake, and was unresponsive.

The rest of the class began spot-probing the debris around Rider 2’s sled. They set up a probe line and searched the debris systematically, but could not locate Rider 2.

Members of GCSAR and the Grand County Sheriff’s Office arrived at the avalanche at 3:10 PM and joined the rescue effort. They extracted Rider 1 from the watery debris and performed CPR for about 45 minutes. GCSAR continued to search for Rider 2. They suspended the search and rescue effort when darkness, blowing snow, and poor visibility made it difficult to evaluate additional avalanche hazards.

GCSAR and the Grand County Sheriff’s Office resumed their search on Sunday morning, January 8. They brought additional resources including personnel from Colorado Parks and Wildlife, US Forest Service, US Bureau of Land Management, forecasters from the Colorado Avalanche Information Center, two avalanche rescue dog teams from the Winter Park Ski Patrol, and RECCO detectors. Flight for Life transported the dog teams to the accident site. While the dog teams searched the debris, the RECCO operator detected a signal. The rescue team probed the area and located Rider 2. They excavated Rider 2, who was fully submerged in the lake water beneath about 2 feet of avalanche debris. The team transported his body out of the field.

Comments

All of the fatal avalanche accidents we investigate are tragic events. We do our best to describe each accident to help the people involved, and the community as a whole better understand them. We offer the following comments in the hope that they will help people avoid future avalanche accidents.

There are some basic things you can do to stay safe in avalanche terrain. 1) Read the avalanche forecast every time before you go into the backcountry. 2) Make sure everyone in the group is properly equipped with avalanche rescue equipment (avalanche transceiver, probe pole, and shovel). 3) Get some training to recognize and avoid dangerous conditions and dangerous terrain. 4) Only expose one person to dangerous slopes whenever possible. Making travel choices to avoid avalanches without basic avalanche safety training is hard. The party of three riders did not have any formal avalanche training.

If someone in your group is buried in an avalanche, your partners are their best chance of survival. There are numerous dedicated and skilled search and rescue groups in Colorado, but as the Grand County Search and Rescue member relayed to Rider 3–it takes time for them to organize and deploy. Even if they can do that in an hour, that may be too long for a person buried in avalanche debris to wait. Your group needs to have avalanche rescue equipment and know how to use it. At a minimum, that equipment includes an avalanche rescue-transceiver, probe pole, and shovel. You’ll need a transceiver to locate your friend, and probe pole to pinpoint their location, and a shovel to dig them out. Digging in avalanche debris can be a slow and difficult task, so you need a strategy to dig efficiently and minimize the amount of debris you need to move. In this situation only two of the riders were equipped with transceivers and one was carrying an avalanche probe. Rider 3 struggled with his avalanche transceiver, which slowed his response. He did not have an avalanche probe and was forced to dig around the snowmobiles with his shovel to try to locate his friends. This was a slow and tiring process with a limited chance of success.

It is a standard avalanche safety practice to expose just one person at a time to any avalanche hazard. The most common way to do this is to travel through avalanche paths or sections of avalanche terrain one at a time. This means avoid waiting or regrouping in avalanche runouts, ride on steep slopes one-at-a-time, and make a plan before you go into avalanche terrain on how you’ll help your partner if they get stuck on a steep slope. All of these concepts are taught in snowmobile-specific avalanche safety courses.

Lakes are dangerous terrain traps that can make rescue more complicated. Riders 1 and 2 were the fourth and fifth fatalities in the Front Range involving lakes. There was a fatal avalanche accident on this slope on February 14, 2021. Lake water also complicated the 2021 accident. In January 2016, an avalanche on St Marys Lake, about 6.5 miles south of Pumphouse Lake, caught and killed a climber. The avalanche broke the lake ice, and the climber’s legs were partially submerged. In November 2001, an avalanche caught two backcountry skiers and shattered the ice on Yankee Doodle Lake, about 1.5 miles east of Pumphouse Lake. The slide swept one skier into the middle of the lake, and he swam through about 200 feet of broken ice to reach the shore.