If it seems like enormous wildfires have been constantly raging in California in recent summers, it’s because they have. Eight of the state’s ten largest fires on record—and twelve of the top twenty—have happened within the past five years, according to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire). Together, those twelve fires have burned about 4 percent of California’s total area—a Connecticut-sized amount of land.

Two recent incidents—the Dixie fire (2021, above) and the August fire complex (2020)—stand out for their size. Each of these burned nearly 1 million acres—an area larger than Rhode Island—as they raged for months in forests in Northern California. Several other large fires, as well as many smaller ones in densely populated areas, have proven catastrophic in terms of structures destroyed and lives lost. Thirteen of California’s twenty most destructive wildfires have occurred in the past five years; they collectively destroyed 40,000 homes, businesses, and pieces of infrastructure.

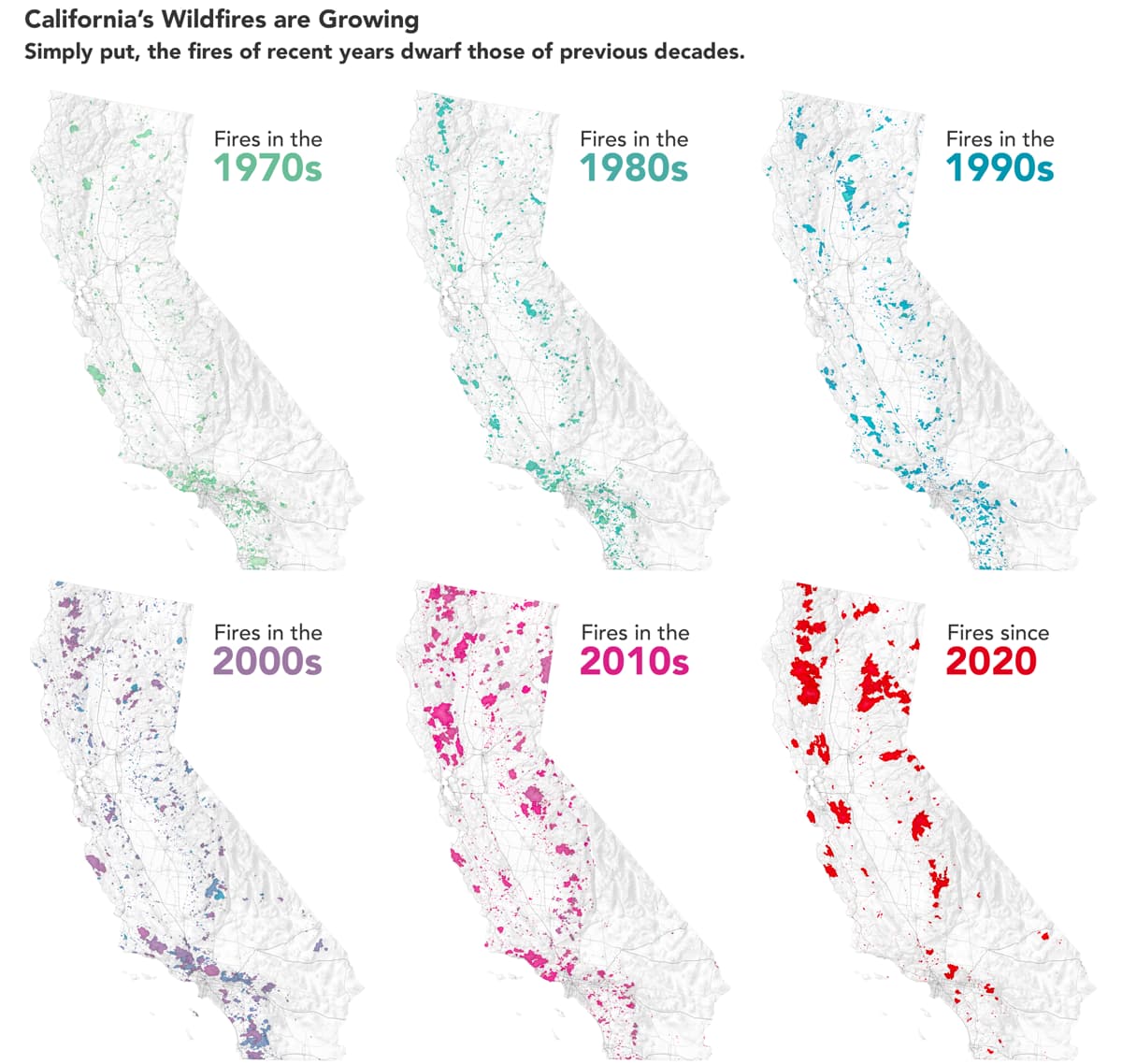

The total area burned by fires each year and the average size of fires is up as well, according to Keith Weber, a remote sensing ecologist at Idaho State University and the principal investigator of the Historic Fires Database, a project of NASA’s Earth Science Applied Sciences program. The database shows that about 3 percent of the state’s land surfaces burned between 1970-1980; from 2010-2020 it was 11 percent. The shift toward larger fires is clear in the decadal maps (above) of fire perimeter data from the National Interagency Fire Center.

“The numbers are really worrisome, but they are not at all surprising to fire scientists,” said Jon Keeley, a U.S. Geological Survey scientist based in Sequoia National Park. He is among several experts who say a confluence of factors has driven the surge of large, destructive fires in California: unusual drought and heat exacerbated by climate change, overgrown forests caused by decades of fire suppression, and rapid population growth along the edges of forests.

The effects of all these fires are dramatic from the ground and from space. The false-color image at the top of the page, captured by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8, shows the burn scar left by the Dixie fire. The blaze destroyed 1,329 structures and cost hundreds of millions of dollars to fight. The photograph below shows charred forests in Plumas National Forest in the wake of the Dixie fire.

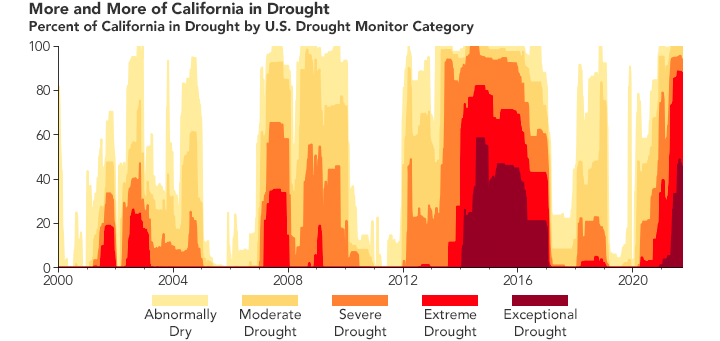

“The current drought is unprecedented,” said Keeley. “Each of the past three decades has had substantially worse drought than any decade over the last 150 years.” In the short-term, drought exacerbates fires by sapping trees and plants of moisture and making them easier to burn. Over the long-term, it adds vast amounts of dead wood to the landscape and makes intense fires more likely.

The 2020-2021 drought has been especially extreme. “The last two years in California have brought compound drought conditions—effectively, very dry winters followed by relentless summer heat and atmospheric aridity,” explained John Abatzoglou, a climate scientist at the University of California, Merced. “This has left soil and vegetation parched across much of California, so the landscape is capable of carrying fire that resists suppression.”

Data from the Western Regional Climate Center indicates that the northern two-thirds of the state received only half of normal rainfall over the past few years. The U.S. Drought Monitor has categorized about 85 to 90 percent of California as experiencing “exceptional” or “extreme” drought for all of summer 2021. And the period between September 2019 and August 2021 ranked as the second-driest on record for the state, according to data from the National Centers for Environmental Information.

Daniel Swain, a climatologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, added that one of the most direct ways that climate change is influencing California fires is by dialing up the temperature. “Heat essentially turns the atmosphere into a giant sponge that draws moisture from plants and makes it possible for fires to burn hotter and longer,” he said. Meteorological data shows that the two-year period from September 2019 through August 2021 ranks as the third-warmest on record in California, with temperatures that were roughly 2.9° (1.6°C) degrees warmer than average. Air can absorb about 7 percent more water for every degree Celsius it warms.

Abatzoglou noted that some of the harrowing scenes across Northern California in 2020 were due to an extreme and unusual dry lightning siege in mid-August that ignited thousands of fires in one night. “But in 2021 I am less convinced of bad luck,” he said. “Climate change is aiding in the warming and the more rapid drying of fuels that predispose the land to large fires.”

This article first appeared on NASA Earth Observatory and was written by Adam Voiland.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens and Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey, fire perimeters from the National Interagency Fire Center, and drought conditions from the U.S. Drought Monitor/University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Photograph courtesy of InciWeb.

This guy as a fire scientist has some pretty in depth analysis of California fire behavior, overgrown forests, historic fires, and forest thinning operations.

The world should be listening to experts with boots on the ground.

This is a man made problem, and climate change is likely making things worse than they would be otherwise but it is not the primary culprit. It is also not the solution to the problem.

https://the-lookout.org/

Here’s another map of how the Dixie fire stopped dead in its tracks at older fires from 2019 & 2020. Obviously that’s common sense the fuel is gone.

https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/photos/CALNF/2021-07-19-1409-Dixie-Fire/picts/2021_10_03-12.10.56.922-CDT.jpeg

When you compare a forest that saw fire 10-15 years ago with the forest that hasn’t seen fire for 100 years you realize the tree density / acre is 5x-6x thicker.

Everyone keeps preaching climate change as the culprit, and assume by fixing global warming we will fix our wild fire problem. Unfortunately that is not true. The forest needs to be returned to a more natural cycle where it sees fire every 10-15 years. At that point, we will have the massive wild fires back under control.

Its a shame the media and and probably some enviros beat the forest service over the head when they don’t perfectly execute a procedure that in the long run helps us out. That egg on their face phenomenon is partially to blame for the forest service being so gun shy about doing what is right. They are damned if they do and damned if they don’t.

Super uncool and super counterproductive.

That “controlled burn” got out of control and torched the area. That was a sore spot for some USFS folks who are now not feeling so bad.

But yes, proactive forest management works. A good non-burn example is on the west ent of Mormon Emigrant Trail and around Sly Park Lake where the under cover has been thinned/removed leaving what a low-intensity fire would leave (maybe less). The fire got to that area and stopped cold. There are several other sections along MET that have been similarly thinned in recent years although I cannot place them exactly on a map to compare to the fire perimeter. I would love to see an overlay of thinning operations and fire perimeter.

Did anyone else notice how the large hole in the fire perimeter just North of Kirkwood was a controlled burn from 2019? It was called the Caple Creek Controlled Burn.

AKA proactive Forest Management? Seemed to work.

https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/photos/CAENF/2021-08-15-0910-Caldor-Fire/picts/2021_09_29-08.57.38.259-CDT.jpeg

Wildfire naturally occurs every 10-15 years. Most of the Sierra’s haven’t seen wild fire in 100+ years. As the saying goes its pretty hard to fight mother nature.