Avalanches are a powerful force of nature that should not be reckoned with. They’re powerful, destructive, and hard to predict. There are so many factors that can contribute to snowpack instability, it’s hard to remember all of them. The goal of this article is to bring awareness to one of the most important of said factors.

When it comes to backcountry enthusiasts, the term “weak layer” is one of our least favorite words to hear. A weak layer can be summarized as a weakness in the snowpack that may cause avalanches or other snowpack instabilities. To learn more about weak layers, this video does a great job of summarizing snow science.

One way that a weak layer can form is by dew. A dew point is a temperature at which air can no longer hold water. Since warm air can hold more moisture than cold air, dew usually forms at night when lower temperatures mean the same moisture that was comfortably held in the air during the day reaches 100% RH (relative humidity) and deposits on the ground as dew. (A similar phenomenon happens when a moist cloud hits a mountain range. The air temperature gets cold enough to force moisture out, precipitating rain or snow. This is known as orographic lift.)

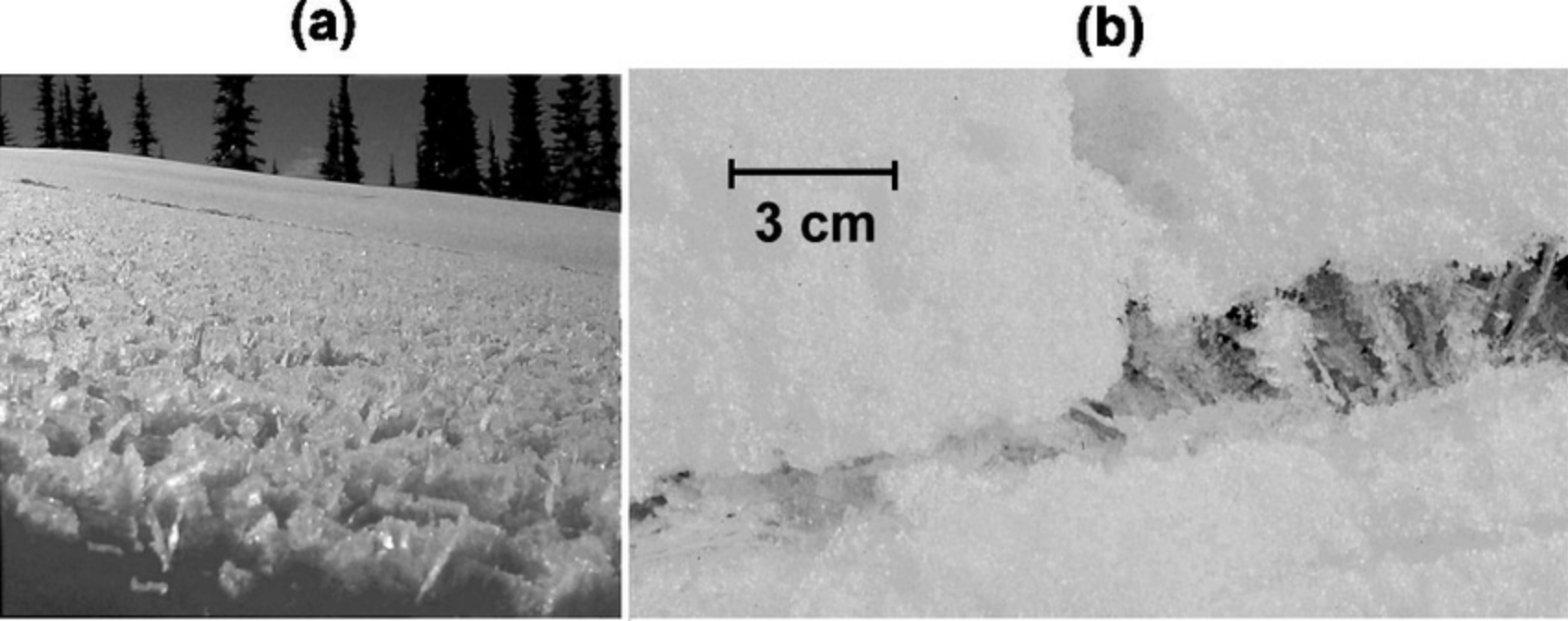

In the mountains during winter, if the air temperature hits the dew point, the dew deposits on the surface of the snow and freezes into a structure known as surface hoar. Surface hoar is large frozen crystals of water ice that are stunningly beautiful and even better to ski on. When skiing over surface hoar, it almost sounds like shattering glass. To summarize: surface hoar is awesome.

Surface hoar is not so awesome when it becomes buried. This is where it becomes dangerous and poses serious implications for avalanche safety. The crystals are relatively strong. They can tolerate feet of snow falling on top of them. If the snow falling on top of the buried surface hoar becomes a cohesive layer, things get very dangerous. The crystals are loaded with snow on top of them, so it doesn’t take much pressure for them to collapse. This pressure might be a rockfall, cornice fall, or likely a skier. The way I like to explain it is like an elephant standing on Jenga blocks. When the crystals collapse, the entire cohesive snowpack above them is unsupported and avalanches. The tricky thing about buried surface hoar is that it propagates readily, meaning an avalanche can span the entire width of a slope.

Unfortunately, there’s not much that can be done about buried surface hoar. You can’t really select terrain to avoid it since it forms on all aspects on all elevations (all elevations that reached the dew point, that is). Sometimes wind and sun can help break the crystals down before they become buried. The only way to verify this is by digging a snowpit to see for yourself. While there isn’t much you can do about it, it’s good to be aware if there is surface hoar and adjust your plans accordingly (i.e. staying out of avalanche terrain!).