When most people make a plan to have an alpine adventure like skiing, snowboarding, or climbing, they make plans for how they will stay safe and have a good experience. They check the weather so they can plan what to wear. They plan out travel to get the timing just right. If going into the backcountry, they research the state of the snowpack and check avalanche safety for where they want to go. Most people don’t think about the invisible dangers; like a potentially deadly condition that can be hard to recognize at first if they don’t know what to look for, and gets more dangerous if ignored.

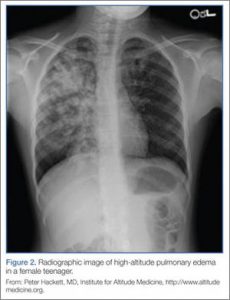

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema, or HAPE, is a dangerous medical condition where the lungs fill with fluid when they come into a high altitude environment from a lower altitude environment. Cases are most common above 8,200ft but have been reported over 4,900ft for more vulnerable people. Being aware of HAPE is important because if left untreated it can lead to symptoms like difficulty breathing (dyspnea), discoloration of the skin (cyanosis), and has a mortality rate of up to 50% if left untreated.

Symptoms of HAPE are:

- Shortness of breath

- Coughing

- Bluish skin (commonly lips and fingers)

- Crackles or wheezing while breathing

- Rapid breath or rapid heart rate

- Coughing discharge

Many cases arise just from people ascending too quickly but there are pre-existing conditions that exist that can increase the chances of developing HAPE. These conditions include individual susceptibility due to low hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR), use of sleep medication, excessive salt ingestion, being in a cold environment, and heavy physical exertion, and even just being of the male sex, so if any of these relate to you, it is even more important to be aware.

Being out at high altitudes, in cold temperatures, and physically exerting our bodies are all part of the territory in snow sports, making this a common occurrence in the places we go to participate in these rad sports.

A study done in Colorado by Paul Auerbach for Wilderness Medicine in 2017, found that 1 in every 10,000 visitors developed HAPE, making 150 cases in 39 months – as this is only up to 9,606ft. This means that although it’s more likely at very high altitudes, cases do occur in the normal range of altitudes where our ski areas are, making it a realistic possibility for anyone in these areas. Venturing outside the bounds of ski areas is an even higher risk at this altitude (and higher). Not having professional medical help close by makes it less likely to be treated quickly and exerting oneself more intensely when ascending increases HAPE’s likelihood.

The higher you go in these mountain environments, the likelihood of developing HAPE even higher. At 4,500m (about 14,000ft) the incidence is between 0.6% and 6%, but as you go up to 5,500m (about 18,000ft) the incidence goes up to 2% to 15%. The chances of developing HAPE also increase the faster you ascend, and physical fitness hasn’t been shown to affect the likelihood of contracting HAPE, so it is best to take time and acclimate, especially on high alpine routes.

HAPE usually sets in the first 2-4 days above 8,200ft, whether visiting a high altitude environment or returning back to one from a lower altitude environment. If the time is available, taking some time to get used to the altitude can decrease the chances of developing HAPE. Even on the trails or at the resort, making a gradual ascent is recommended along with the same guidelines for acute mountain sickness and High Altitude Cerebral Edema.

For even higher altitude areas, especially mountaineering or exploring high in the backcountry, acclimating is even more important. The Wilderness Medical Society (WMS) recommends that “above 3,000 metres (9,800 ft), climbers should not increase the sleeping elevation by more than 500 metres (1,600 ft) a day, and include a rest day every 3–4 days (ie, no additional ascent).” When venturing out into these environments it’s important to have the necessary information and planning to stay safe, accounting for HAPE in the plan.

If you do start noticing excessive shortness of breath while ascending, shortness of breath at rest, dry cough, or any blueish discoloration (commonly on the lips or fingers), descend to a lower altitude as quickly as possible. While descending, it’s important to keep the level of exertion down. There are drugs used for high blood pressure and barometric treatments that can assist, and in mild cases, rest and supplemental oxygen can improve symptoms. In any case, descending is the best treatment, even if it means putting off that sweet line for another year. In more extreme cases hospitalization is required and can be very serious with mortality rates up to 11%, and 50% if left untreated. After contracting it, it’s important to make changes next time because HAPE has a 60% recurrence rate since many cases are triggered by pre-existing conditions or poor planning.

Taking HAPE into account is always important to remember when planning to make a trip to altitude. There are inherent risks when going out into the mountains. There are natural dangers like temperature or avalanches, or danger caused by an activity like skiing, snowboarding, or climbing. Danger from illnesses caused by the environment is no joke and needs to be avoided and planned around, just like other physical risks. So next time you are elevating yourself in the mountains, remember to take your time on the approach and pay attention to how you and the members of your party feel, it could save a life.