A woman was injured after she triggered, got caught, and was partially buried in an avalanche while out hiking on Saturday 2nd May. The woman was in a group of seven hikers descending Horn Peak’s northeast ridge and started to slide down a steep snowy slope toward a snow-filled gully. Going first, she triggered a wet avalanche which carried her 1,000-feet. She was partially buried with her head above the snow.

Below is the full report from the Colorado Avalanche Information Center:

Avalanche Comments

This was a wet loose-snow avalanche unintentionally triggered by a climber while glissading down a snowfield. It was small relative to the avalanche path, and large enough to bury or injure a person. The avalanche entrained 12 to 24 inches of wet snow, including old snow (WL-AFu-R1-D2-O). The wet avalanche was about 40 feet at the widest point and ran over 1,000 vertical feet.

Backcountry Avalanche Forecast

A Special Avalanche Advisory was in effect for the Northern, Central, and Southern Mountains of Colorado from 4 PM May 1 until 8 PM May 3.

The regional backcountry avalanche forecast for the Southern Mountains, issued on the afternoon of May 1, rated the avalanche danger on May 2 as Considerable (Level 3). The Highlights section read:

Dangerous wet avalanche conditions continue through the weekend. The potential to trigger a large Loose Wet or Wet Slab avalanche increases as the day heats up. Wet snow problems are not isolated anymore to sunny slopes and we’re seeing an increase in size and distribution of wet avalanches on all aspects and elevations. Avalanches that start near the top of the snowpack can gouge deeply into the snowpack and entrain a lot of heavy, wet debris. Smaller avalanches are triggering deep and long-running wet slabs, in some instances taking out the entire snowpack depth.

Plan to start very early and be out of avalanche terrain before supportable crusts break down. Choose your terrain to avoid traveling across or below any slopes steeper than about 35 degrees with wet, cohesionless snow. Signs that the conditions are deteriorating include a slushy snow surface, a punchy snowpack that no longer supports your weight, pinwheels and rollerballs, and wet avalanches running from steep rocky terrain.

Weather Summary

The South Colony SNOTEL site sits about five and a half miles to the southeast of the accident site at 10,800 feet. It is the closest weather station to the site. Throughout most of November snowfall was sparse and daily minimum temperatures were in the low teens to single digits for much of the end of the month. On December 1, 2019, the measured snow depth at the South Colony SNOTEL was 24 inches. On February 22, 2020, the South Colony SNOTEL registered its maximum snow depth for the season of 55 inches. By May 1, 2020, the snowpack had shrunk by half and the measured snow depth was only 26 inches.

From April 29 to May 2, the day of the accident, the minimum temperature did not drop below 34 °F, while daytime high temperatures ranged from 59 to 62 °F. On the day of the accident, the observed air temperature at the start of the day was 40 °F, well above freezing, and the maximum air temperature reached 59 °F. In those same three days, the snowpack lost seven inches of total height and on May 2 the start of the day snow depth was 23 inches.

Snowpack Summary

Warm temperatures at the end of April and beginning of May resulted in a significant loss in snowpack depth in the Sangre de Cristo range. At the beginning of May, some of the only remaining snow above treeline was in previously wind-drifted terrain features like gullies. At the avalanche site, investigators found 16 to 18 inches of wet, unconsolidated, cohesionless, polygrain crystals in the starting zone. There was no distinct layering in the snowpack. The snowpack on the eastern side of the gully was composed of weak, wet, cohesionless crystals, similar to the starting zone. The avalanche entrained the full depth of the wet snow. There were areas of dense snow in the center and western edge of the gully. The avalanche ran over these denser areas and only removed the wet snow. The avalanche left a berm where the wet snow was removed and a few mounds of denser snow that were overrun by the avalanche.

Events Leading to the Avalanche

A group of seven friends met at the Horn Peak trailhead at 7:00 AM on Saturday, May 2. Of the seven in the group, five were from the Westcliffe area. Most of the group had wilderness first-aid experience, and four of the party were experienced search and rescue volunteers. One of the local group members organizes a group hike on a weekly basis. Most members of the party had previously climbed this peak. The route is visible from town. They could see that the route was mostly snow-free. They did not intend to travel on snow and did not discuss the possibility of avalanches. The party typically carries an ice ax in the event they needed to cross a steep snowfield or to aid in glissading. They did not anticipate using them on this climb.

The group reached the summit of Horn Peak around noon. Climber 3 was first to summit. The group had lunch and enjoyed time on the summit. About an hour later they began their descent. They regrouped near the top of a snow-filled gully. Climber 1 and Climber 2 decided they wanted to glissade down the gully. Their main concern was that the snow was too soft, and they would sink in too far to slide down the gully. Climber 1 got her ice ax out, sat down, and began to slide down the slope.

Accident Summary

Climber 1 started down the gully at about 2:45 PM. Climber 2 stood at the top, waiting for her to finish. Climber 3 stood in the grass adjacent to the gully watching. After Climber 1 made it about 200 feet down the gully, Climber 3 observed a large amount of snow building up behind her. Climber 3 yelled to Climber 1 to get off of the slope but she was unable to get out of the way. The wet loose-snow avalanche overtook Climber 1. Climber 3 described the avalanche as a “Class 5 river with 3-foot waves of snow.” They watched as Climber 1 was repeatedly submerged under the moving snow and then resurfaced.

The avalanche gained volume and speed as it cascaded down the slope carrying Climber 1 down the gully and out of sight of Climbers 2 and 3. Climber 3 had cell service and immediately called Custer County Search and Rescue and 911. He then ran down the grass next to the gully looking for Climber 1.

Rescue Summary

Climber 1 was near the toe of the avalanche when it stopped. Her torso and arms were buried in the debris, but her legs and head were above the surface. She knew she was hurt and desperately wanted to move off the snow and into the grass, which was only about four feet away. She was able to wiggle her arms and dig herself out with her hands. She crawled off the avalanche debris and laid in the grass waiting for help.

Climbers 3 and 4 were the first to reach Climber 1. The rest of the party arrived shortly after. They assessed her injuries and changed her into dry clothes. She was in significant pain and having difficulty breathing. The group re-established communications with Custer County Search and Rescue (SAR) and advised them that Climber 1’s injuries were serious. A Flight for Life helicopter was dispatched from Pueblo. Members of the party set up a landing zone (LZ) approximately 150 feet downhill from Climber 1’s location.

Flight for Life spotted the party around 4:00 PM. The pilot attempted to descend but could not land due to strong winds. The pilot made several attempts to land and eventually had to leave to refuel.

The Custer County SAR team assembled in Westcliffe and started hiking into the avalanche at 6:00 PM. Climber 3 and another party member left the avalanche site to rendezvous with the SAR team. They returned to the accident site around 8:30 PM. Rescuers placed Climber 1 in a vacuum splint and a litter and lowered her to the LZ.

The Colorado Army National Guard was activated to assist in the rescue and flew a Blackhawk helicopter from Buckley Air Force Base. The helicopter arrived above the site around midnight. The helicopter was unable to fully land but did manage to drop off a rescuer before taking off again. This rescuer briefed the ground crew on the extrication. They moved Climber 1 to a specific location in the LZ. The helicopter descended again. Without fully touching down, the helicopter crew loaded Climber 1 into the helicopter. They lifted off and flew to Westcliffe where Climber 1 was transferred to a waiting ambulance.

Fremont County Search and Rescue, El Paso County Search and Rescue, and Alpine Rescue Team also assisted in this rescue.

Comments

The group did not intend to travel on snow, and thus did not read the avalanche forecast or discuss avalanche conditions in advance. They were not carrying avalanche rescue equipment. A portion of the group made a spur-of-the-moment decision to move onto the snow and glissade. Had the group planned for on-snow travel and read the avalanche forecast, they would have seen that the avalanche danger was Considerable (Level 3 of 5) with a Special Avalanche Advisory warning people about wet avalanches. Checking the weather and avalanche forecasts is an important part of planning any trip to the mountains. These products may prompt you to anticipate hazards you had not yet considered.

The members of the group were very familiar with the terrain. They had safely glissaded down snowy slopes at similar times in previous years. Although the snow coverage in the gully looked similar to past conditions, the snowpack was not similar. Multiple days with above-freezing temperatures left the snowpack wet and unconsolidated on May 2. The wet loose-snow avalanche quickly entrained a large volume of the unconsolidated wet snow.

In this accident, a fairly small avalanche, on a slope with very little snow, caused a serious injury that required a helicopter evacuation. The group did not consider avalanches as one of the hazards they needed to address when they decided to glissade this slope. Even small avalanches can be quite dangerous, depending on the terrain they carry you through. Wet loose-snow avalanches can be surprisingly powerful and difficult to get out of once they start moving. This accident is a good reminder that you need to consider the avalanche hazard any time you encounter snow on an inclined slope.

Avalanche Details

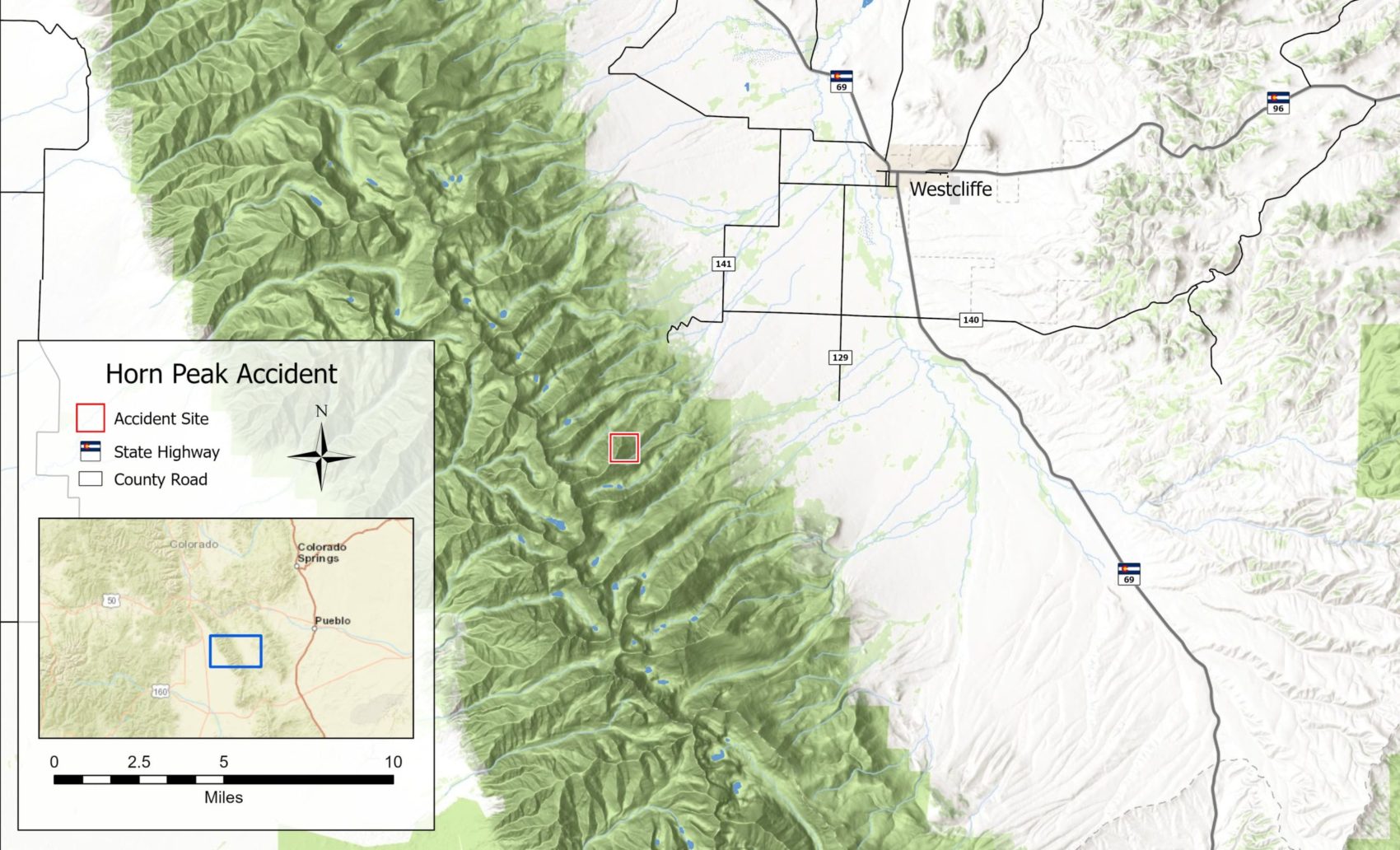

- Location: Horn Peak, Sangre de Cristo Mountains

- State: Colorado

- Date: 2020/05/02

- Time: 2:45 PM (Estimated)

- Summary Description: 1 climber caught, injured

- Primary Activity: Climber

- Primary Travel Mode: FootLocation Setting: Backcountry

Number

- Caught: 1

- Partially Buried, Non-Critical: 1

- Partially Buried, Critical: 0

- Fully Buried: 0

- Injured: 1

- Killed: 0

Avalanche

- Type: WL

- Trigger: AF – Foot penetration

- Trigger (subcode): u – An unintentional release

- Size – Relative to Path: R1

- Size – Destructive Force: D2

- Sliding Surface: O – Within Old Snow

Site

- Slope Aspect: SE

- Site Elevation: 12400 ft

- Slope Angle: 36 °

- Slope Characteristic: Gully/Couloir