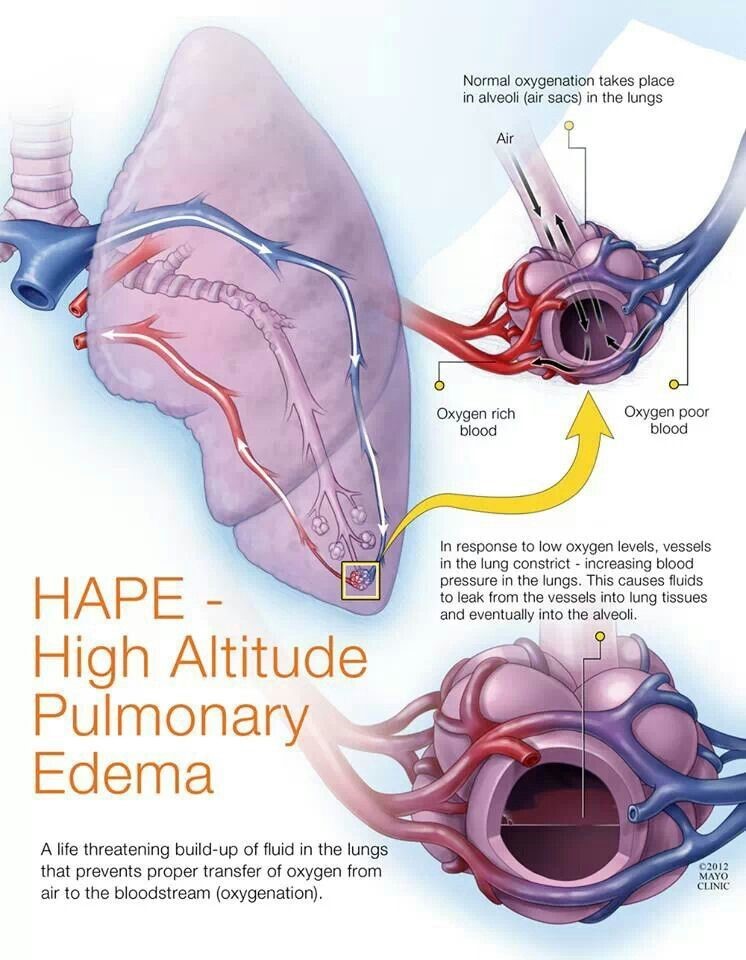

You may think that slippery slopes, nasty falls, avalanches, wild animals, or gear malfunctions are the most dangerous things in the mountains, but you must beware of HAPE. This little, seemingly harmless acronym stands for High Altitude Pulmonary Edema, and that mouthful of words can kill you, literally. It’s the number one cause of death related to high altitude exposure.

HAPE occurs when fluid begins to accumulate in the lungs after traveling to a higher altitude. Though more detailed studies need to continue to learn more about this disease, we do know that it begins to present its signs at 2,500 meters in healthy people, and cases have been seen at 1,500 meters in some who are more predisposed to altitude sickness.

So how do you prepare? Being able to read the warning signs is the first step. The Lake Louise Consensus has set the criteria for the symptoms of HAPE for us. If you show 2 or more of these in either category, you need to stop what you’re doing, descend if possible, and seek professional help. Here they are.

Symptoms:

• Shortness of breath at rest

• Cough

• Weakness or decreased performance

• Tightness of chest or congestion

Signs:

• Wheezing or crackling while breathing

• Central blue skin color

• Rapid breathing

• Rapid heart rate

Or, here’s a quick reminder that I’ve come up with.

H – Hard to breath

A – Accelerated heart rate

P – Persistent cough

E – Exhausted performance

So, you may ask, “What’s the best way to set yourself up for success when heading to the mountains?” Take a day when arriving at a new altitude to acclimate, take time to explore the town, try some unique local cuisine, and experience the hometown vibe before heading up the mountain. I know, lame right? But please don’t stop reading now. If you simply cannot wait to get the goods, like most of us, then make several lower mountain laps, or take lower elevation hikes at first to test how the altitude is affecting you before heading right to the summit on the first chair.

Factors like cold exposure, gender, and intense physical exertion raise your risks. H.A.P.E. was diagnosed as pneumonia and other un-related diseases for many years before we began to learn more about it. You will normally notice signs and symptoms within the first 2-4 days at altitude, with evidence of fatigue, a dry persistent cough, and dried cracked lips. In many instances, people will begin to notice abnormal consciousness or cerebral edema. For preventative measures, the Wilderness Medical Society (WMS) recommends that climbers over 1000 meters, take it slowly, while not increasing base camp elevations by more than 500 meters a day and if at all possible, stop to rest every several days.

If you do develop H.A.P.E. you should descend to a lower altitude immediately, to seek professional help, which often involves a hyperbaric chamber. If that is not possible, you need to be warm, full of rest, and take oxygen if available. Oxygen needs to be administered at a low rate. After being treated you will be given Nifedipine to ingest prior to future expedition that require large elevation changes.

Now that you are more aware of H.A.P.E, and the best way to avoid or recognize it, it’s time to strap up and get after the goods! Remember to ski/ride fast and take lots of chances, but be aware of this silent killer lurking behind your next elevated adventure.

It takes 3 weeks of acclimation to build up more/enough red blood cells to get the blood oxygen up. We humans are only good up to 12k feet in terms of epo production.

Alcohol bad.