Everything we know about avalanche mitigation work can be traced back to Alta, Utah—one way or another. 57% of the 9-mile Little Cottonwood Canyon Road (Where the town of Alta is tucked away)is in an avalanche runout zone making it one of the most avalanche-prone roads on earth. For Alta inhabitants, avalanches are a part of life.

Little Cottonwood Canyon is a box canyon—one way in, one way out. Avalanches have affected everybody living and working in the canyon since Alta’s early mining days in the late 19th century, according to Damian Jackson, the Avalanche Safety Supervisor for the Utah Department of Transportation at Alta. People have known that the area around Alta is avalanche-prone because people have died from avalanches as far back as the 1880s. However, it wasn’t until 1939 that Alta became North America’s very first avalanche research center.

In 1938 the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) issued a special use permit to Alta Ski Area, allowing it to open as a ski area the following year, according to UDOT. The USFS knew that avalanches were a major threat to the Little Cottonwood Canyon Road (SR 210) and to everybody in the canyon. So in 1939, the USFS hired Douglass Wadsworth as the first Forest Service Snow Ranger whose job it was to minimize avalanche hazards on SR 210. Wadsworth created the first avalanche safety rules in North America for skiers and people traveling on the Little Cottonwood Canyon Road which state that people should stay out of Little Cottonwood Canyon for a few days during and after storms, that they should keep off of or under steep slopes with no trees after a storm, and not to park under avalanche paths. This was only the beginning.

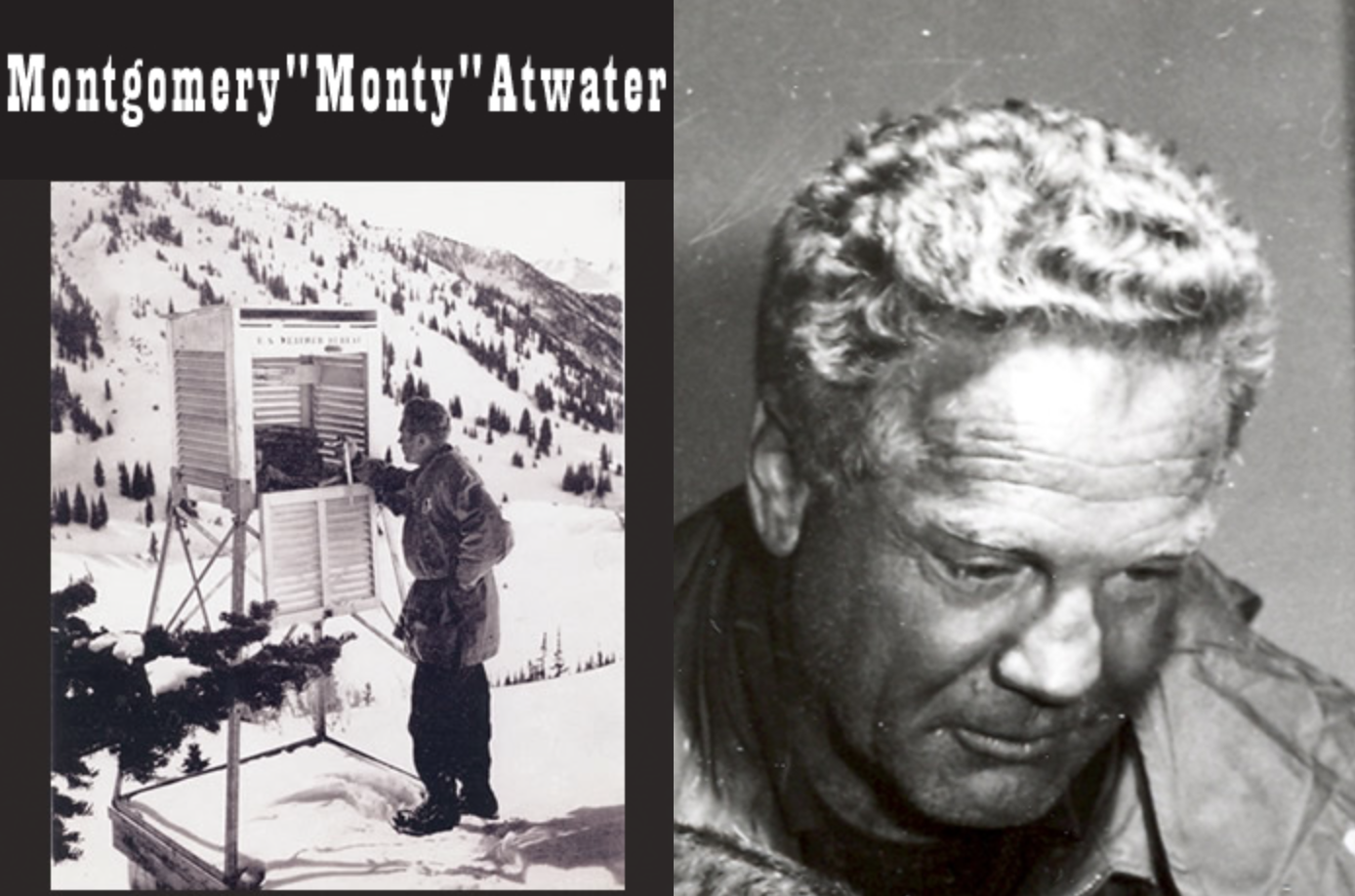

Monty Atwater arrived on the scene in 1946—an ex-10th Mountain Division soldier who the USFS hired as Alta’s first Snow Ranger. He was essentially an avalanche hero who changed the mitigation game forever. Atwater has been called “the Grandfather of Avalanche Forecasting,” and, after being discharged from the 10th Mountain Division in World War II due to an injury, Atwater became the first person in the nation to work with military artillery for avalanche control. He had seen artillery guns used to make avalanches in Italy during WWII and decided to use that same framework for avalanche mitigation work on several slopes at Alta. So he worked with the Utah National Guard and got himself a 75mm French Howitzer to blast for avalanches.

- Related: The History of the Legendary 10th Mountain Division, The Men Who Started USA’s Ski Industry

This was the first time that military artillery was used for avalanche control in North America and it was the start of what is now a highly-complex, multi-faceted avalanche safety plan for both the Big and Little Cottonwood Canyons. It was a tremendous success and it wasn’t long before the USFS changed their policy and allowed Atwater and other Forest Service Snow Rangers to legally shoot the military artillery without having to ask the National Guard for permission every time they wanted to trigger avalanches.

Atwater later wrote in a book labeled “The Avalanche Hunters,” in 1968:

“That Alta was ideally conceived by nature to become the first avalanche research center on this continent and that I was there to take the plunge were mere coincidences.”

Thus, in 1949 Alta became home to the first official avalanche center in the western hemisphere until 1972, when the Forest Service moved the Alta Avalanche Study Center to Fort Collins, Colo. Ironically, that December, a huge avalanche struck the Alta Lodge, filling the top floors with snow and depositing a Volkswagen Beetle on the roof.

Over the course of its 70-year-and-going history, avalanche mitigation work continues to evolve—at Alta and elsewhere. Anti-tank rounds are no longer fired at the mountains to trigger slides, and artillery rounds are not used as frequently as they once were. Now, more technical methods are used to mitigate for avalanches such as Gazex exploder systems, which are positioned gas-exploders that release propane gas to trigger slides.

This is how a Gazex exploder operates:

According to Jackson, Gazex exploders are placed at several locations above SR 210 including Hellgate, above the Snowbird village, and above the bypass road in an area called “Black Jack.” On scary, avalanche-prone days, these systems are the primary way used to mitigate avalanches on SR 210. And even with this futuristic technology, mitigating avalanches is still no easy task.

Avalanches are inherently complicated, tricky, and dangerous to work with. According to Jackson, Snow Ranger Monty Atwater once referred to the jutting and powerful Mount Superior located on the highway opposite Alta and Snowbird as “a blonde bitch—cunning and beautiful, but treacherous.” For Mt. Baldy, which shares the boundary between Alta Ski Area and Snowbird, Atwater referred to it as “a grizzly bear—beautiful, but able to kill you with just one swipe,” and High Rustler like “a wild mustang always showing the whites of its eyes,” as Jackson paraphrased from Atwater’s book, “The Avalanche Hunters.” And for Jackson and his crew at UDOT, their least favorite avalanche path in LCC is White Pine—the spot where a highway maintenance worker was killed in the ’70s.

70 years onwards, avalanche mitigation work in Little Cottonwood Canyon keeps evolving. More and more Gazex and Ovalex (a gas exploder similar to the Gazex system) systems are being installed almost every season and there’s even potential for more, passive avalanche mitigation systems to be put in place, such as snow fences in Europe—something that Jackson and his crew have been advocating for years. Jackson said in a phone interview:

“We have proposals on the table currently for snow [fences] in the mid-canyon in three areas— one covering the White Pine chutes area, one covering White Pine, and one covering Little Pine—which would go a very, very long way in increasing our safety as well as preventing road closures.”

As both the Big and Little Cottonwood Canyons continue to see increased skier visits and increased backcountry use, more and more avalanche mitigation proposals for both passive and invasive avalanche control systems flop onto the table. More people are skiing in the backcountry than ever before—especially this season with COVID-19 as a factor—which could entail more avalanches than ever. More avalanches equal more delays, more road closures, more property damage, and—unfortunately—more deaths. Thankfully, however, this canyon is the home of where avalanche mitigation work all began and it’s not stopping anytime soon.