Snowy mountains serve as natural “water towers” in some parts of the world, storing vital fresh water in frozen form during cool, wet times and releasing it in warmer, drier seasons. In central Chile, however, a megadrought, ongoing since 2010, has disrupted this dynamic. The prolonged dry period has often left seasonal mountain snowpack thin, straining water supplies, exacerbating wildfires, and parching crops. Winter 2023 brought some relief.

The respite is due in part to two atmospheric rivers that delivered abundant rain and snow to the region. A relatively cold spring followed and left the Andes’ water towers much fuller heading into the dry season than in recent years.

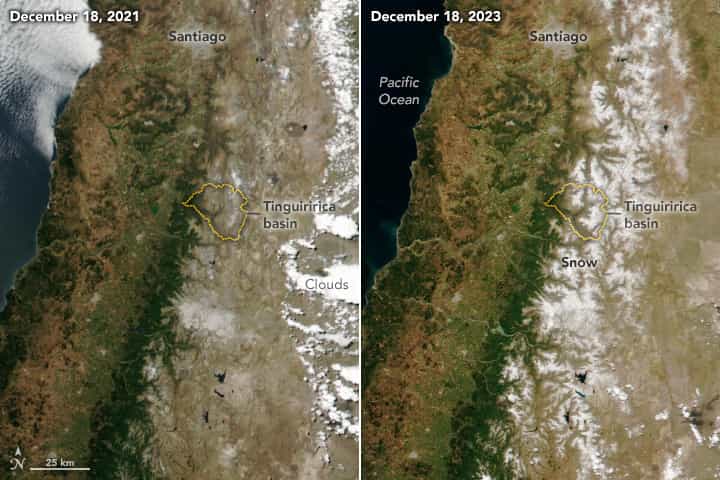

The difference in snow cover is apparent in this image pair. On December 18, 2023 (right), at the start of summer in the southern hemisphere, seasonal snow still blanketed the Andes, straddling Chile to the west and Argentina to the east. On the same date in 2021 (left), much less snow and ice remained following a very dry winter. Both images were acquired by the VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) on the NOAA-20 satellite.

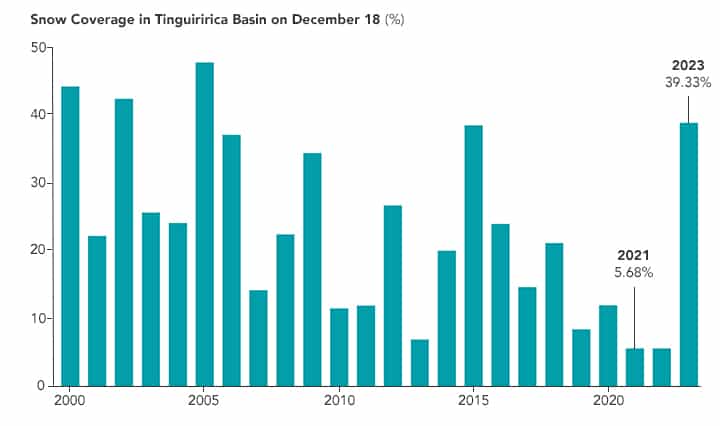

Data from the Observatorio de Nieve en los Andes de Argentina y Chile (above) show that mid-December snow coverage in the Tinguiririca Basin in 2023 stood well above levels seen in the past several years. The observatory supports a digital platform using data from NASA’s MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) sensors to track snow cover in Andean drainage basins over time.

“The seasonal snowpack—often depleted by this time of year—is hanging in there. And that is pretty good for the rivers draining the Andean basins on both sides of the Chile–Argentina border.”

– atmospheric scientist René Garreaud of Universidad de Chile

The Tinguiririca Basin, south of Santiago, feeds one of the major rivers flowing from the subtropical Andes to the Pacific Ocean. It provides water to the O’Higgins Region, an important agricultural area in Chile’s Central Valley known for its fruit orchards and wine production.

Amid the brighter signs of a healthier snowpack and water sources refilling, Garreaud cautions this wet year may represent not so much an end but a mere interruption to the megadrought. “Climate change is pushing central Chile towards a drier climate,” he said. Regional models project a 35-45 percent decrease in Andes snowpack by mid-century, even in a low greenhouse gas emission scenario, a recent study found.

This post first appeared on NASA Earth Observatory. NASA Earth Observatory images by Wanmei Liang, using VIIRS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE, GIBS/Worldview, and the Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS). Snow coverage data from MODIS, processed by the Observatorio de Nieve en los Andes de Argentina y Chile, IANIGLA-CONICET and (CR)2. Basin boundary data from Camels-CL Explorer. Story by Lindsey Doermann.