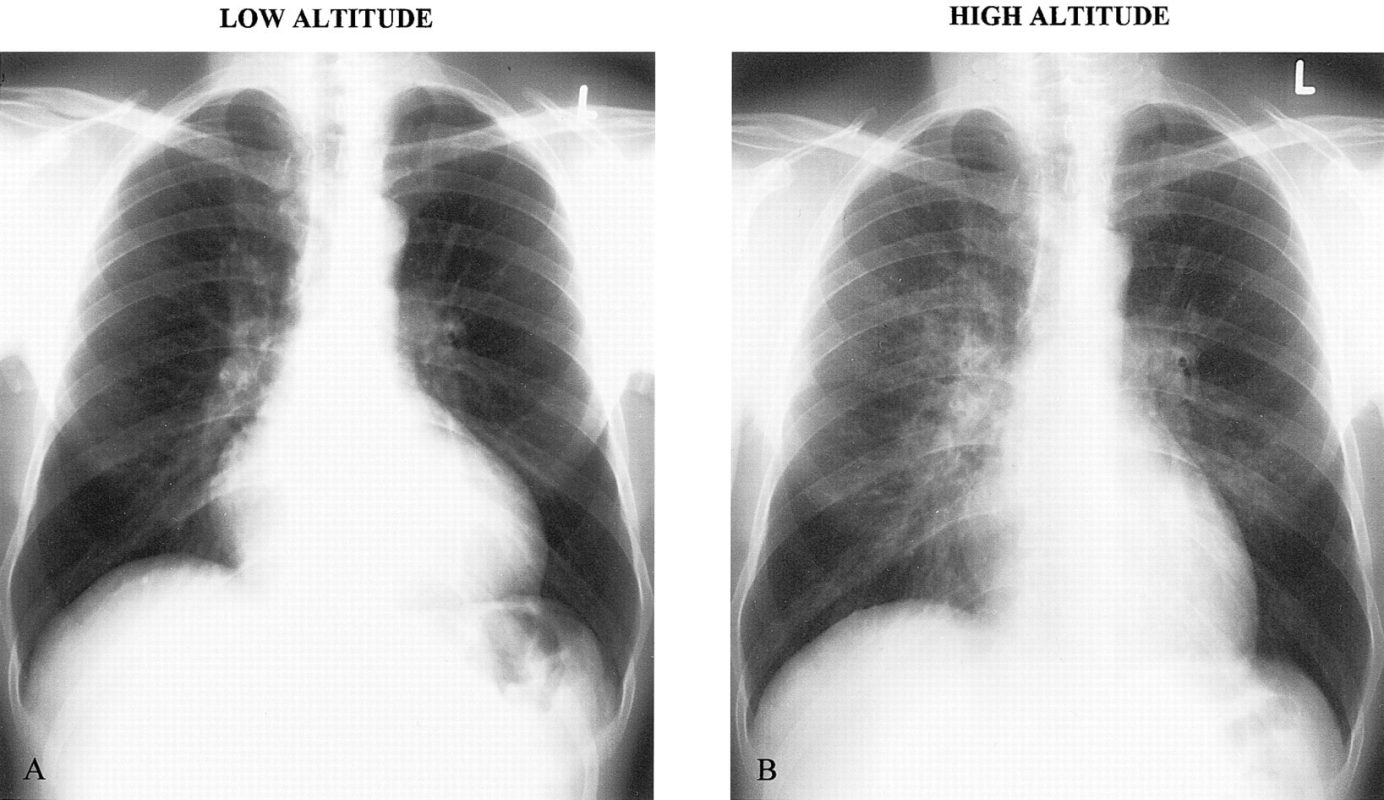

For the avid mountain enthusiast, honing the management of risk and wellbeing while being exposed to the extremities of upper alpine environments is for some, what draws us to the challenge of such adventures. At higher altitudes, that starting from 1500metres (4900ft) our bodies and more so our lungs begin to operate at a lower oxygen dense environment and the risk of developing HAPE (High altitude pulmonary edema) occurs when our pulmonary system (lungs) begin to fill will fluid, rather than the oxygen-rich fuel we are accustomed too at low levels of elevation.

For our physical bodies that require the deliverance of oxygenated blood to our depleted or somewhat exhausted respiratory system and muscles, the development of HAPE can have seriously fatal outcomes to an individual regardless of their previous health status and conditioning. Small irritable symptoms, such as; a minor cough, headache, nausea, and fatigue are the result of minor altitude sickness. Poor circulation can cause lips to turn blue, heart rate to turn rapid and signal to remain at current elevation while taking in liquids, keeping warm and resting. The skill of acclimatization is key, taking it slow and refueling, while allowing the body to become comfortable adapting to such extremities.

Any and all symptoms can increase over 12 to 24hours of reaching upper alpine environments leading to the probable outcome of developing a more fatal situation. Coughs can produce a white/pinkish phlegm as the lungs cells become inflamed and headaches leading to confusion and irrational decision making as cognitive performance decreases.

Urgent procedures like altitude sickness medication, additional oxygen supply, or rescue would need to be administered with the onset of such symptoms. The wilderness medical society (WMS) recommends that when ascending above 3000m (9,800ft) to not increase your daily elevation by more the 500m (1600ft) per day and rest every 3-4days with no additional ascent.

The most effective solution is to lower your elevation if symptoms continue or worsen. With noticeable differences made to individuals with just 500m (1600ft) of descent dependant on the severity and condition of the individual. In an environment so demanding, the slow and steady have the best chances of success.