Epic Adventure on the Elephant’s Perch: Late October Climb & Bivy on the Mountaineer’s Route (5.9 III)

by Michael Dunning & WanderHigh.com

Back in May, my brother Andrew and I set a goal for ourselves: to climb the Elephant’s Perch by the end of the season. The Elephant’s Perch is a 9,870′ peak located in the Sawtooth Wilderness outside of Stanley, ID. While not the tallest alpine wall in Idaho, it is arguably the highest quality and most popular alpine rock face in the state. First climbed in 1963 by the accomplished mountaineer Fred Beckey and friends, there are now over 25 established routes on the Perch, ranging from 5.9 to 5.12. We would be climbing the 800′, 6-8 pitch Mountaineer’s Route (5.9 III). Several months ago climbing this route seemed like a lofty goal. I learned to rock climb almost 15 years ago while living in Los Angeles, exclusively climbing indoors — with the exception of one trip to Joshua Tree. With our adventure time in LA mostly limited to weekends, we pretty much gave up on climbing so we could have time to go to the river every weekend to kayak.

The Elephant’s Perch.

After a ten year hiatus, I bought my first rope a year ago and began rock climbing at the many accessible top-roping spots in Lake Tahoe. I didn’t get much climbing in before winter arrived, so most of my recent rock climbing began in May on my first trip to the City of Rocks. Climbing my first ever lead on a 5.7 sport route at the City and finding it quite terrifying, our goal of climbing the Perch seemed very distant. Over the next six months Andrew and I made several more trips to the City of Rocks, Dierkes Lake, Cedar Creek, the Channel, the Lava Tubes, and several other local climbing spots. Making great progress, I was now confident climbing 5.11 on top rope, leading 5.10 sport routes, and leading up to 5.9 on trad gear. Two months ago I bought my first set of cams and successfully climbed a few easy alpine routes in the Pioneer mountains. After climbing all summer, we felt prepared for the Perch.

Enjoying some fishing on our rest day before the climb.

We decided to make this a laid-back trip: we would spend 3-4 days at Saddleback Lake at the base of the route, with plenty of time for preparation and rest before and after the climb. In summer months the approach to Saddleback Lake is short, as you can take a boat shuttle across Redfish Lake and shave 5 miles off the hike. Being mid-October, we had to start our hike from the Redfish Lake trailhead, bringing the approach to Saddleback Lake to roughly 10 miles. We hiked in on a Tuesday carrying heavy packs filled with climbing, camping, photo, and fishing gear. Arriving just before dark, we cooked up some Chicken Fajita and promptly crawled into our tent.

Lunch.

Waking up on Wednesday to what was supposed to be clear skies, we discovered overcast weather and cold temps. With clouds blocking the sun’s rays, it was hard to get out of the tent. Four packets of hot maple and brown sugar oatmeal and sitting next to a raging fire warmed us up. Just after noon the clouds broke and it warmed significantly. Still hungry, we decided to see if we could catch some lunch and headed to the lake. A hundred casts later and we had ourselves a couple of respectable trout. Andrew cooked them up “caveman style”, with a stick through their mouths and tails, right over the fire — seasoning them with a lemon herb mix and sea salt. Maybe it was because I was hungry, but they were the most delicious fish I’ve ever tasted. We spent the rest of the day lazing around, eating, and shooting video and photos of the gorgeous scenery that surrounded us.

We found lots of “needle ice” around our camp. This strange phenomenon occurs when the soil is warmer than the air, and subterranean liquid is brought to the surface via capillary action, freezing into needle-like columns. I had never seen this before — very cool.

Many times on the night before a climb, I find it hard to sleep. Sometimes I will peek out of my tent to look up at a monolithic silhouette of the mountain I am about to attempt, as if to confirm it is indeed as big and scary as I was imagining while attempting to sleep. Sometimes there are racing thoughts of everything that could go wrong, along with the hope that nothing will. This time it was different. I felt calm and confident and actually got a decent night’s sleep. Not bad for an insomniac the night before his biggest climb.

Enjoying some tea around the fire.

We got out of the tent the next morning at around 8AM to build a fire. Happy to see clear skies, we got the stove going to heat up some water for oatmeal. The high was forecast to be around 50 that day. With no wind, 50 degrees is plenty warm to climb. The problem is, it doesn’t reach that temperature until at least noon. The early hours of the day were in the 30′s. With sunset at around 7PM and with us wrongly estimating that the route would take 6 hours, we thought that if we got on the wall by 11AM, we would have enough time to complete the route — fully expecting to complete the downclimb in the dark. By the time we got to the base of the route, put on some layers, stacked the ropes, and racked up, it was closer to 11:30. I can’t imagine having started too much earlier, as it was very cold at the first belay, which was still in the shade.

The Elephant’s Perch and the “Beckey Tree.”

We didn’t start our first real belay until after two easy chimney moves. Andrew moved through one chimney without placing any pro, found a stance, and belayed me up. We did this again and then started climbing with protection at a point just below an intimidating mantle move. More of a mental crux than anything, I would have preferred to have at least warmed up first. Past the mantle the climbing was easy going, and we continued up to the top of pitch 1, setting up a belay next to a couple of prehistoric bolts. Pitch 2 steepened and was a fun cruiser up a beautiful splitter crack to the only two legitimate bolts on the route.

Approaching the base of the Mountaineer’s Route.

Pitch 3 was fun and exposed. Above the bolts at our belay are a series of roofs that you skirt left of before heading up, around, and into a 3rd class gully. It would have gone smoothly if not for the first of our rope issues. Having not wanted to lead P3 after coming up P2, we decided to do the “pancake flip” method rather than re-stack our ropes (this was our first climb on a new set of half ropes — doubling the amount of rope we had to deal with). It seemed to work until Andrew got about 10m above me and the ropes ended up in a tangle. Trying to untangle 120 meters of ropes got tiring and frustrating. Andrew downclimbed back to me to help sort out the mess. After a quick re-stack, we got moving again and luckily had no issues with rope drag at the roofs. The nature of this pitch was such that communication was impossible. With the tugging on the rope from above signaling it was time for me to climb, I broke down the anchor and climbed around the corner and into the 3rd class gully. It was refreshing to stand on somewhat solid ground, although we were both growing increasingly concerned about our slow progress on the route. Looking at the topo and route photos, we still had a long way to go. We must have both been anxious, because we couldn’t eat more than a few bites of candy and didn’t talk much in the gully.

Andrew below pitch 2, with the triple roofs looming in the background.

While reading online about the route, many people talked about pitch 2′s splitter being the highlight of the climb. Pitch 2 was fun, but pitch 4 was the highlight for me. After leaving the gully, pitch 4 gains an indistinct arête leading to a semi-hanging belay below the final crux. The exposure after climbing out of the gully was immense, looking down a near-featureless vertical face 700 feet to the ground. Maybe it was because we were in a rush at this point, but I felt surprisingly comfortable with the exposure. I feel most comfortable while climbing. It’s the sitting around in a hanging belay not making progress that makes me uncomfortable. Continuing up pitch 4, the crack features were fantastic and varied — from laybacks and the occasional jam to a very fun double-crack tower feature that was a bit hollow sounding. I made quick work of the pitch and helped Andrew mentally prepare for the crux: a short overhang that looked intimidating, especially considering at this point we were in a race to reach the top before the diminishing daylight turned to cold and darkness.

Andrew starting up pitch 2.

Our pitch 5 belay, which consisted of two nuts and a hex triple-equalized with a cordelette, was plenty secure but the most exposed. While the belay was on a less steep part of the slope, ten feet behind me lay a 700 foot drop into the abyss. I couldn’t help but look behind me occasionally, then back at my anchor, and then up at Andrew, who was taking his time making quality placements below the crux. I found my mind wandering, imagining among other things what it would be like to fall 700 feet off the wall. What would it feel like? I wondered. What would you think about during those few seconds of free fall? For that matter, how many seconds would it take to hit the ground? I started to do some math in my head, calculating how long that drop would be, before I snapped myself out of it. Seconds later, I heard a subtle “whoosh” as I saw the rope moving through carabiners in front of me. Without thinking I pulled my right hand down and locked the rope through my belay device. At the same time I heard my brother yell, “FALLING, FALLING.” Already weighting my semi-hanging belay anchor, I braced for the catch, which luckily was smoother than expected. I couldn’t see my brother at this point and called up to see if he was okay. “I’m good. I’m all good.” He sounded surprised. On easy terrain 15 feet below the crux, he had taken his hands off the wall to blow on them for warmth. Thinking his feet were secure, the fall was totally unexpected. The fall was on a fixed cam that he had clipped into. Luckily it held. At this point the sun was dropping fast, and I tried to psych my brother up for the crux, subtly reminding him we were quickly running out of time.

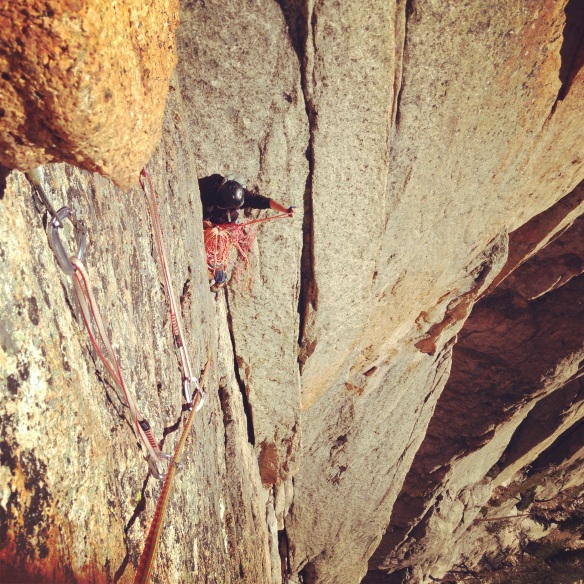

Me coming up the beautiful crack on pitch 2.

As I repeatedly glanced behind me to check the sun’s location in the sky, Andrew continued on, placing a good amount of protection before pulling through the short crux move. It was reassuring to have him back in my line of sight. We both would have flown up this section if the move was on a single-pitch sport route. However, when leading on gear almost 800 feet off the ground, you take your time making quality placements and finding solid holds. As Andrew tried to pull his way up and over a small overhang on a finger-sized crack, he took another fall. Not quite as dramatic as the first one, it was scary nonetheless. We were running out of time. I shouted up for him to move right to a fist sized crack, which is where he should have been. When he finally pulled over the crux, I was relieved that the hardest part was over…or so I thought. Less than ten feet above, his upward progress was blocked when the rope became stuck in a crack. We both attempted to whip the rope out of the crack, to no avail. As this was happening, I looked behind me to see the sun making its final foray behind the massive spires of the Sawtooths. I looked up to see the last bit of light fade off of the wall like a wave retreating from the shore. I knew we only had minutes until it was dark.

Here I am trying to untangle our mess of ropes at the top of pitch 2.

Above, Andrew made a solid placement, pulled through enough slack to downclimb to the problematic crack, and extended a placement with a longer runner to solve our rope issue. He flew back up, climbed another ten feet, and set up a belay. I climbed up to him as fast as I could, cleaning our gear on the way. Knowing the last pitch was easy fifth-class climbing, I left a couple nuts in the rock as I thought being able to see what I was climbing was more important than losing a couple pieces of gear, as I didn’t have the time to pull out my nut tool and bang them out of the rock. The nuts I left behind were hand-me-downs from my stepdad – 70′s era Chouinard pieces. Having been in service for 30+ years, we felt like we got our money’s worth. Perhaps we will get them back next summer.

After climbing out of the gully on pitch 4, the exposure increased drastically.

When I reached Andrew at the belay, he handed me some gear. I took the lead and probably climbed faster than I have ever climbed. After about 150 feet of no-pro low fifth-class climbing, I reached flat ground, found a stance, and brought Andrew up on hip belay. At this point I was overcome with a huge feeling of relief. Still unaware that we would be spending the night up high, we were simply happy to be off the wall. As we caught our breath and started organizing gear, I looked out and enjoyed one of the most beautiful scenes I have ever experienced in my years in the mountains. The post-sunset twilight was filled with beautiful blues, reds, and purples, with snow-capped, craggy peaks silhouetted against a clear but darkening sky. It was a much-needed moment of calm after a couple intense hours.

Halfway up the route, looking south.

This brief moment of calm ended quickly when I scrambled up another 20 feet to look for the route to the descent gully. Glowing in the twilight, I discovered a beautiful but dangerous scene. In summer months this 4th class slope of rocks and slabs would easily be crossable in the dark. Now it was covered in 2 feet of snow, with our vision limited to the 20-foot beam of our headlamps. It seemed impossible. We spent 20 minutes scrambling around, looking up, looking down, looking for any way to safely make the crossing. I looked at my brother and said, “I think we’re bivying tonight.” Glad to have packed an emergency bivy sack and regretting my decision to keep our packs light by not bringing a sleeping bag, I looked for a spot to hunker down.

Arriving at the top of the route in near darkness.

Seeing what we thought was a tree 150 feet below us, I slung a runner around a rock and tied off a single rope, put a knot in the end, and threw it into the darkness. While I brushed snow off some rocks and laid our other rope out to use as a pad in preparation for our luxury accommodations for the night, my brother rappelled down to find some wood for a fire. Over the next hour Andrew collected a backpack full of wood. I made a small fire pit and tried to get our home for the night as comfortable as possible. Using a klemheist hitch to help ascend our fixed line, Andrew eventually returned, exhausted. With branches and sticks protruding every which way from his backpack, he was looking more like a scarecrow than a person.

The view from our bivy the next morning, looking towards Redfish lake.

Still warm from our movement, we decided not to start a fire until we needed it. Ten years ago my dad bought me and my brother lightweight emergency bivy sacks. Having never even taken one out of its stuff sack, we usually brought one of them with us on extended outings, just in case. The sack is essentially a glorified space blanket, but slightly more durable, sewn into a sleeping bag shape. We laid our second rope down on the rock for insulation and both carefully crawled into the sack. Within minutes we were surprisingly warm. Not surprisingly, sharing a sack with another person while on top of a pile of rocks is not very comfortable. Realizing we were in for nothing more than a cold night, we were able to somewhat relax, talk, process, and laugh. At this point our biggest concern was that we would be late for our Friday night start-worrying-about-us deadline that we set with family and friends before heading out. We planned to get up at first light, make the traverse to the descent gully, and get to Stanley as soon as possible to check in via cell phone.

Me and Andrew in the morning after emerging from our bivy sack, ready to get off the mountain.

A few hours later the temperature dropped and we were not only uncomfortable, but uncomfortable and very cold. Andrew’s feet were wet from his wood gathering escapade and were starting to get numb. Having spent an unexpected night out in the winter over ten years ago with him that resulted in nerve damage to my toes, I helped him warm up his feet and suggested he put his now-diminished hand warmers into his shoes. At this point we decided it was time to start a fire. Sadly, our mostly green wood didn’t turn into the fire we had hoped, but 30 minutes of desperately blowing to keep the small flames going warmed us up just enough that we stayed comfortable for another couple hours. Having only brought a liter each of water on the route, and down to a 1/2 liter total at the beginning of the night, we took one small sip each every hour or so. After what seemed like days, and a total of maybe five minutes of sleep, light began to fill the sky. We hopped out of “bed,” packed up our bivy, coiled our ropes, and spent about 20 minutes analyzing the slope to choose our route to the descent gully. Seeing it in the daylight, we were happy with our decision not to cross it in the dark.

Sunrise view looking Southwest from our bivy site.

We chose our route. We planned to downclimb about 200 feet, cross a flatter snow slope, and then head up through rocky 4th class terrain. With a mix of slippery wet rock, powder snow, and ice, we short-roped and simul-climbed through the terrain, occasionally setting up a hip belay on steeper rock sections for added protection. With Andrew a little banged up both mentally and physically from leading the majority of the route the day before, I led the way through the maze of snow and rock. The sun’s rays were rapidly getting stronger, and climbing in all our layers, it was great to experience warmth again.

Cold and ready to get moving in the morning.

Finally reaching the descent gully, we downclimbed, careful not to trip and take a tumble in our exhausted state. At the bottom of the gully, only one obstacle remained until we were safely back at camp: a short rappel. Never one to trust old gear, I cut a length of webbing, backed up the rappel, and descended, experiencing a massive sense of relief that we were finally safe and on solid ground. Andrew followed, I coiled the rope, and we headed back to camp.

On the snow-covered traverse on the way to the descent gully.

We were very happy to have two liters of water waiting for us. We drank, refilled, drank some more, and then ate an entire block of cheese, a half-pound of bacon, two packs of ramen, some jerky, and a couple Clif bars. While it would have been nice to crawl into the tent and sleep for 24 hours straight, we had to get back to Stanley as quickly as possible to assure our family that we were okay. After breaking camp, we hoisted our packs onto our backs and headed towards Redfish lake. When we reached the south end of the lake, we stopped by the docks, hoping a boat would be there that could give us a ride back across. Of course, there wasn’t. We filled up our waters, ate a quick snack, and headed up the switchbacks — finally reaching the trailhead parking lot a few hours later. Completely sore and fully exhausted, we hopped into Old Betsy and headed North on Highway 75, Stanley bound for burgers and cell service.

Andrew follows me through snowy terrain.

If you look closely, you can see our route through the snow. Our bivy site was in the small notch just left of center in the top of the photo.

Just before the final rappel back to camp.

The always beautiful Sawtooth valley a few miles from the car.

Great trip. killer report. thanks.