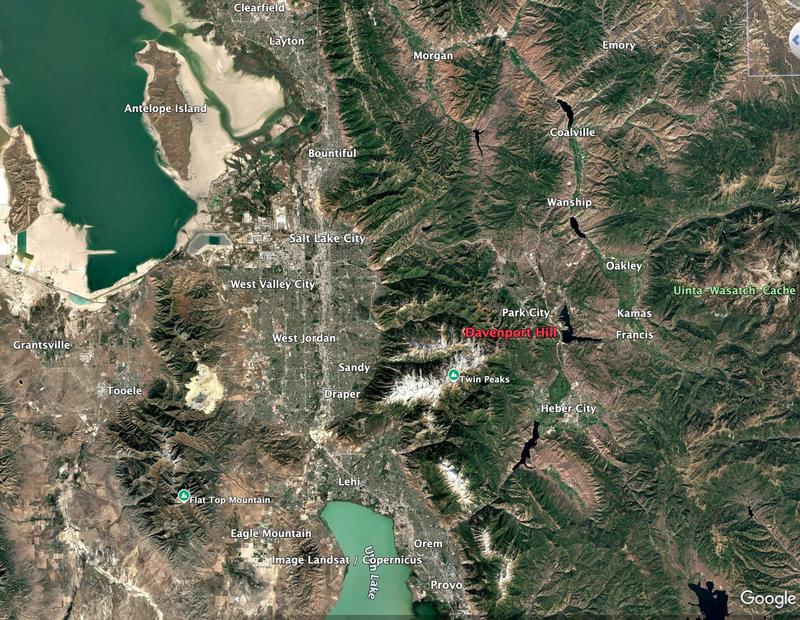

A 54-year-old man died in an avalanche on Tuesday, December 31, the second avalanche-related fatality in Utah’s Wasatch Mountains in three days after another snowboarder was found dead in Millcreek Canyon near Salt Lake City. The incident occurred in the Davenport Hill area north of the ridge separating Big and Little Cottonwood Canyon, east of Salt Lake City.

The man, a solo splitboarder named Reed Heil, was buried 20 feet deep when rescuers eventually dug him out. A burial of this depth, even with rescuers immediately present, is almost always fatal. In Heil’s case, he was alone, which further diminished his chance of surviving the burial.

The Utah Avalanche Center has released a full accident report detailing the all of the events leading to Heil’s burial along with key takeaways. Reports like these are made from entities like the Utah Avalanche Center as a means to shed light on tragedies and educate the public in order to avoid similar future avalanche accidents. The full report is attached below.

Accident and Rescue Summary

Sometime on the morning of December 31, 2024, a solo splitboarder named Reed Heil dropped into north-facing Davenport Hill, in the Silver Fork Drainage of Big Cottonwood Canyon. He was soon caught, carried, and buried twenty feet deep in the avalanche and unfortunately did not survive. Another party skiing the terrain to the south in Little Cottonwood Canyon noticed a single track into fresh avalanche debris and called Alta Central.

This single track dropped off the north side of the ridge into upper Silver Fork, on the rider’s right side of Davenport Hill. The reporting party couldn’t see where the track exited but did see the track covered over by avalanche debris a couple hundred feet below the ridge.

At approximately 12:00 PM, a witness reported the incident to Alta Central, initiating a coordinated response from search teams, including AirMed, DPS, the Utah Department of Transportation, Salt Lake Search and Rescue, Wasatch Backcountry Rescue, Alta Ski Area, and the Utah Avalanche Center. By early afternoon, search teams opted to use a long-range receiver already in the air following recovery operations from a nearby fatality in Porter Fork. The receiver detected a faint signal, leading Wasatch Backcountry Rescue to survey the area and assess the terrain from the air. Their observations revealed a distinct track entering the avalanche debris without any sign of exit, combined with the signal, strongly suggesting human involvement.

Due to unstable conditions in the surrounding avalanche terrain and the heightened risk of secondary slides, teams determined that initial avalanche mitigation would be required before safely deploying rescuers.

Rescue Summary

Explosive control teams from UDOT working with DPS performed avalanche mitigation and brought down several more large avalanches that subsequently allowed rescuers to access the site.

Helicopters dropped off two teams (four people) at the toe of the debris with an avalanche rescue dog named OC, and one team (two people) was dropped off higher on the debris pile to begin a transceiver search there to the toe of the debris. The secondary avalanches that were triggered with explosives most likely put more debris over the burial site. This was an inevitable part of the rescue process to prevent further harm to the search teams.

The teams converged on a location on the uphill side of a gully feature near the toe (bottom) of the avalanche, where they detected a transceiver signal. The lowest signal they got indicated a depth of 20 feet (6 meters), which was too deep to obtain a probe strike initially. Digging began at 3:30 PM (1530 h), with the transceiver still showing a depth of 6 meters. By 3:55 PM (1555 h), they achieved a probe strike at a depth of 9 feet (2.8 meters).

At this point, another team (three people) skied down from the ridge, conducted a secondary transceiver search of the debris, rejoined the initial party, and began assisting with the excavation. By 4:50 PM (1650 h), the victim was fully excavated and extracted from the hole. The team immediately initiated chest compressions before transferring the patient to an AirMed helicopter, which transported them off-site.

The rescue teams found the individual using an avalanche transceiver; he was buried approximately 20 feet down from the snow surface. The victim was buried in a terrain trap and was pushed up a south-facing gully feature. There was approximately 3 feet (1m) of snow below his burial location.

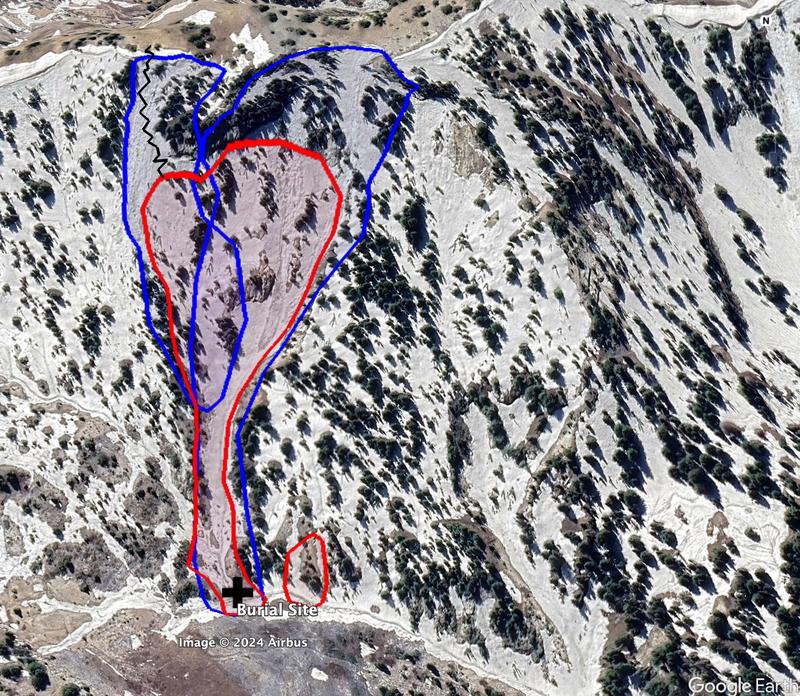

Terrain Summary

This avalanche occurred on a north-facing slope in upper Silver Fork. The crown face was between 9,800 and 9,900 feet and approximately 400 feet wide. The toe of the debris was approximately 9,500 feet in elevation, and slope angles ranged from 35 degrees to well over 40 degrees in steepness. The victim skied off the ridge into a run called Easy Does It and underneath a run called Over Easy. The primary avalanche involved the Over Easy avalanche path. The secondary avalanches included the remainder of Over Easy, and the steeper terrain of Easy Does It.

Below is an overview of the slide paths and debris. The red shapes depict the initial avalanche, while the blue shapes depict the secondary, explosive-triggered avalanches and debris.

Weather Conditions and History

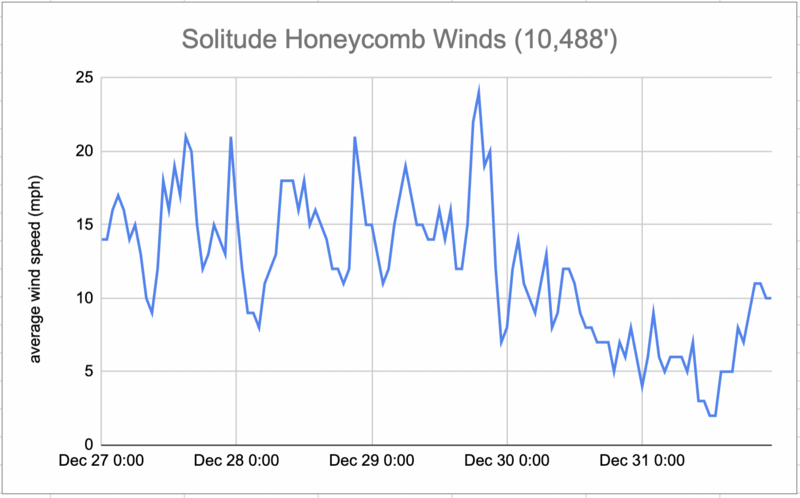

The storm system brought coastal-like conditions to the region, characterized by prolonged precipitation, heavy snow, and strong winds. On 12/27, the weather started with light to moderate snowfall and moderate winds, but conditions quickly deteriorated as the system intensified on 12/28 and 12/29. Winds were particularly extreme during this time, with gusts reaching up to 100 mph on the highest ridgelines.

Snowfall was consistent and heavy, with snow densities increasing as temperatures warmed on 12/28 and 12/29, raising the potential for wet, loose avalanches at lower elevations. By 12/30, the storm began to weaken and shift eastward, bringing a decrease in snow intensity and wind gusts, though winds did remain strong at higher elevations on 12/30. On 12/31, conditions began to clear, allowing the snow to settle and temperatures to drop. The inversion settled in, leaving behind cold, clear conditions in the mountains.

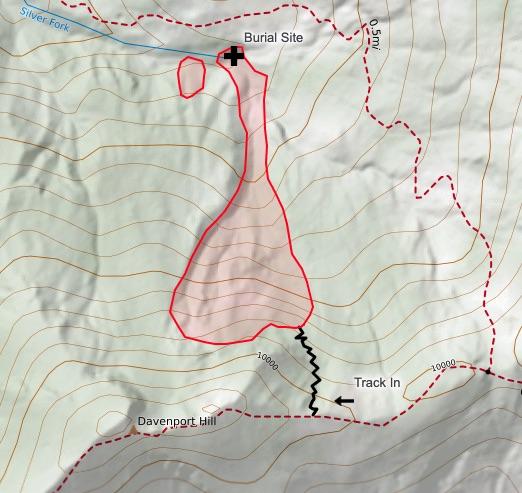

Temperature Data

Temperature run and average air temperature from Solitude Honeycomb Peak (10,488’) from December 27th through December 31st.

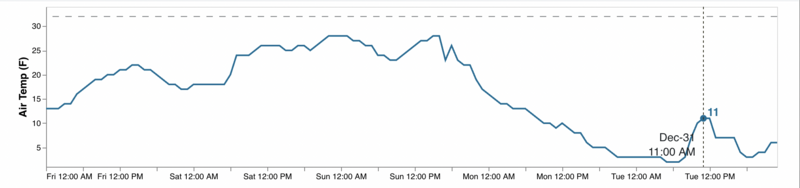

Snow Data

Snow and water totals for the storm cycle from December 23rd through December 31st as measured at the Alta Guard Snow Study Plot located in Little Cottonwood Canyon approximately 1 mile to the southeast of the site of this avalanche.

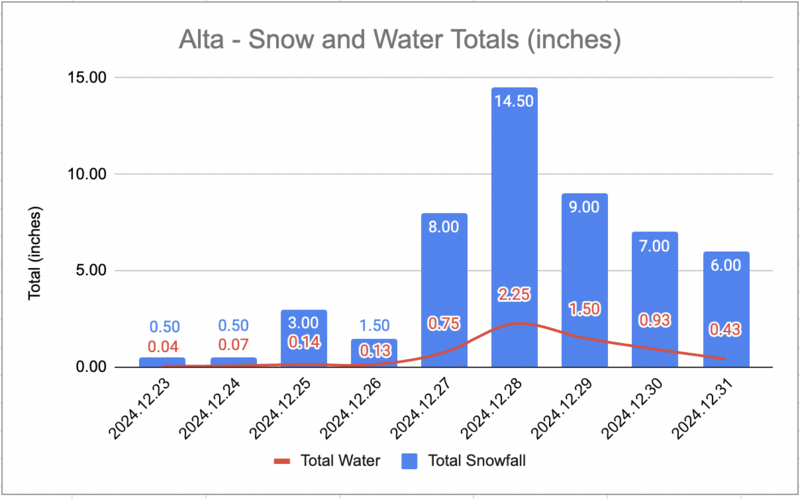

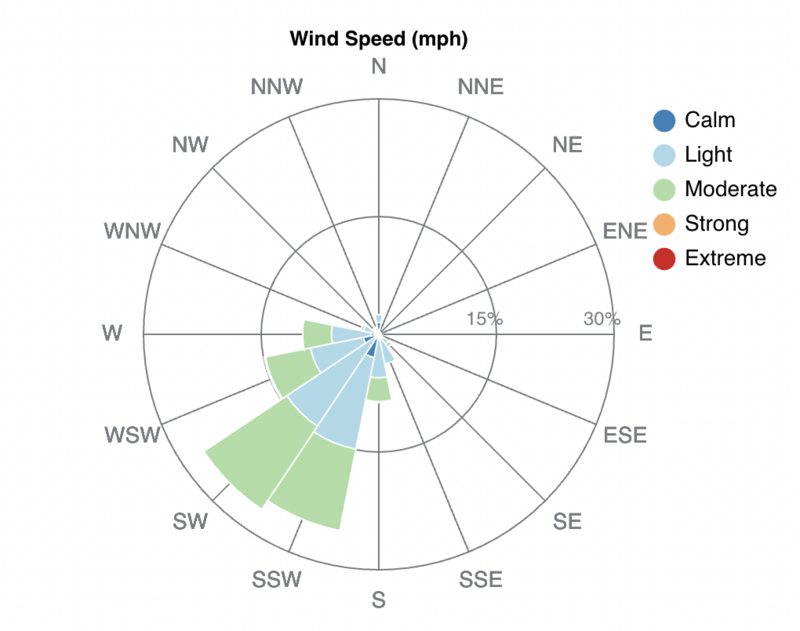

Wind Data

Wind Rose and average speeds from Solitude Honeycomb Peak (10,488’), which is approximately ¼ mile to the east of the site of this avalanche. The graphs show wind direction, distribution, and speeds from December 27th through December 31st.

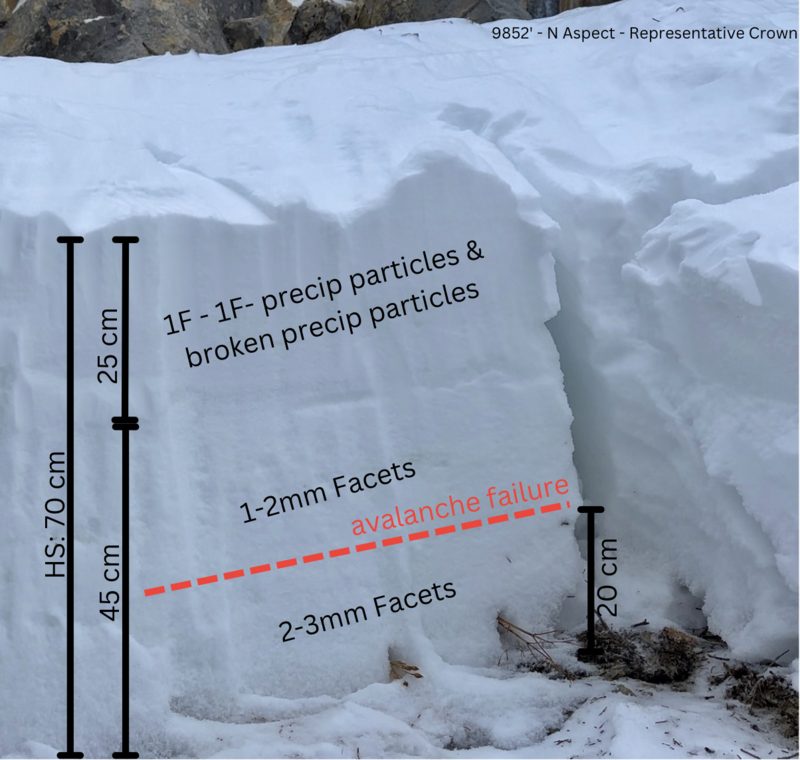

Snow Profile Comments

The area showed a significant impact from additional avalanche control work done prior to rescue and recovery efforts.

The crown was at 9,852 feet on a north-facing aspect directly below a cliff band. Where we dug the pit, the slope was very steep, varying from 36 to 41 degrees, and the snowpack was generally shallow compared to other areas on the slope. At the crown, there were very small new precipitation particles on the snow surface, but the crown remained generally fresh. A bit of new snow had blown in and around. The area was broken and jagged from both the nature of the avalanche and the additional avalanche control work. As a result, the crown profile lacked a downhill side, and efforts were focused on cleaning up the crown wall while attempting to gather information on both the slab and the location of the initial avalanche failure within the snowpack.

The slab was composed of 1F to 1F- precipitation and wind-broken precipitation particles within the upper 25 cm of the snowpack. This sat on a layer of weak, faceted snow. The weak, faceted snow made up the bottom of the snowpack, initially 4F hardness, down to F hardness near the ground. The primary failure layer was about 20 cm above the ground, resting on well-developed 2-3 mm facets. The avalanche stepped down to the ground in shallow areas or places with visible rocks.

Across the bed surface, we found large, well-developed facets, some up to 4-5 mm, with striations, though there was no obvious cupped depth hoar. This emphasizes how extensive and connected the weak layer is throughout the area, which was a key factor in the avalanche accident. The terrain was unforgiving, with a notable terrain-trap gully that concentrated most of the debris.

Snowprofile from the crown at 9852’ below.

Below is the annotated crown section at 9,852’ on a North Aspect directly below a cliff band in a shallow area

Below is the crown line at 9,850 feet on a north-facing aspect, looking west.

Decision Making

As the avalanche victim was traveling solo, there are unanswered questions and we do not know anything about the decision-making process prior to this accident. We do know that the avalanche danger for this location was rated as HIGH in Salt Lake for this aspect and elevation, that an avalanche warning was in effect, and that the avalanche danger had been high for the five days prior to this accident with the primary avalanche concern in the forecasts being the buried persistent weak layer of snow. As of December 31st, 41 avalanches had been reported to the Utah Avalanche Center in the Salt Lake Area Mountains since December 27, 2024.

At the Utah Avalanche Center, we strive to learn from every avalanche incident and share insights to help others avoid similar accidents. We have all experienced close calls and understand how easily mistakes can happen. Our goal with this report is to provide a valuable learning opportunity. With that in mind, we offer the following comments.

Because this avalanche victim was traveling alone, before and during the time of the avalanche, many questions remain unanswered. We are uncertain if the victim triggered the avalanche when they entered the Over Easy Gully feature or if they triggered it lower on the slope. There is a chance it may have also been a natural occurrence. However, this avalanche is assumed to be human-triggered. Given the nature of solo travel and the fact that no one witnessed the avalanche being triggered, we cannot rule out the possibility of a natural avalanche occurring. What is interesting is that they did not trigger the Easy Does It run, and we do know that the avalanche occurred once they entered the Over Easy gully feature. We are thankful to nearby parties that followed backcountry response procedures to allow for rescuers to facilitate a quick response.

We aim to learn from accidents like this and in no way intend to point fingers at victims. Thank you to all the members of the community who participated in this rescue and provided closure to this individual’s family and friends.

Our heartfelt condolences go out to Reed’s family, friends and all those in the community affected by his loss.

Link to UAC field day just after the accident HERE.

Link to UAC field day and snowpits in the weeks leading up to the accident HERE.

Larger overview of location of Davenport Hill (image below)

RIP Reed — your pal Greamer