The Colorado Avalanche Information Center yesterday released its full report from the fatal slide near Breckenridge Ski Area, CO, on December 31st, 2022. The findings can be a learning opportunity for all of us.

The full report is below:

Avalanche Details

|

Number

|

Avalanche

|

Site

|

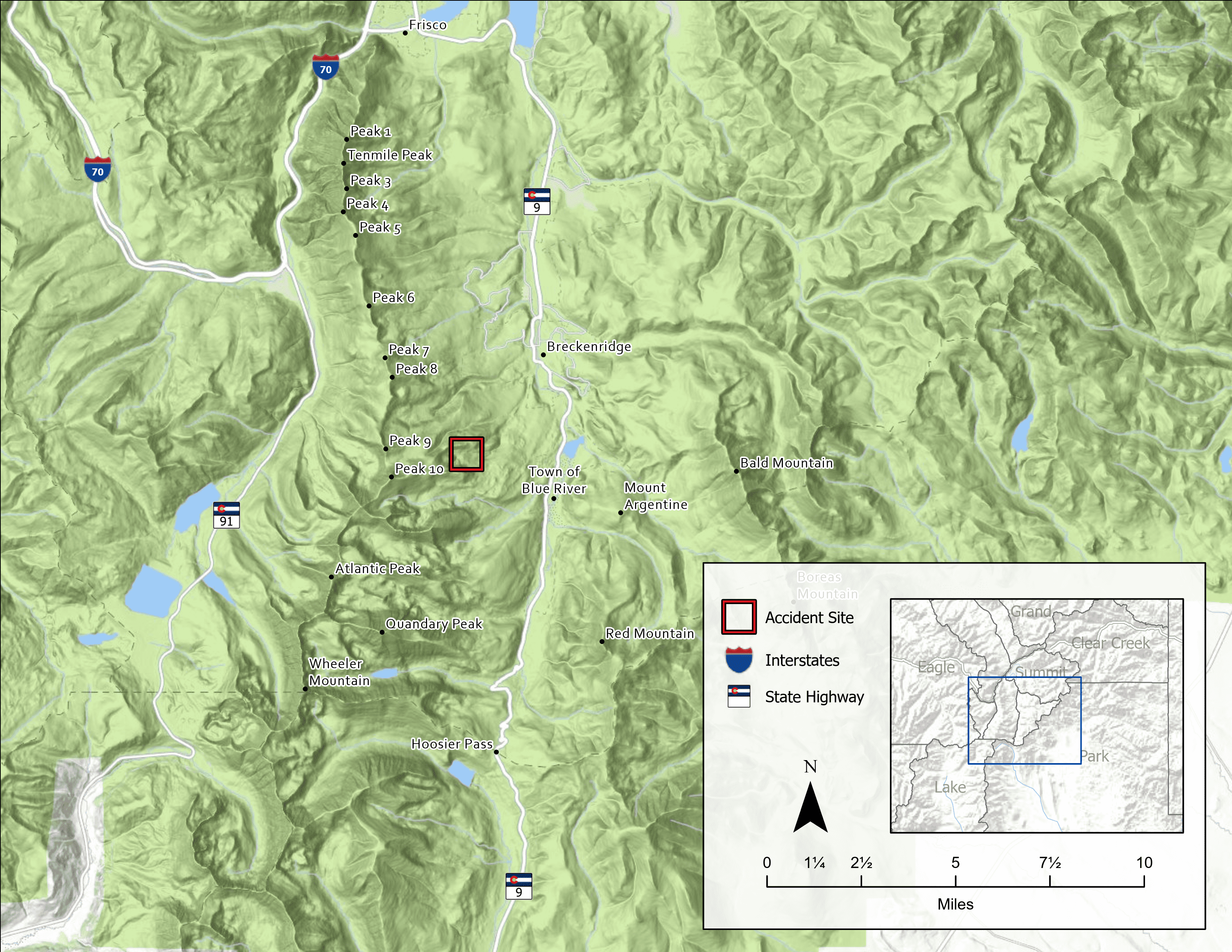

Avalanche Comments

This avalanche occurred in the backcountry outside of the Breckenridge ski area south of Peak 10 in an area locally known as the Numbers. Individual avalanche paths are numbered in ascending order from west to east along the ridge. Number 5, the location of the accident, is the path closest to the ski area boundary, and Number 1 is the farthest away. Number 5 is a steep southeast-facing avalanche path with a start zone that is near treeline. It was a soft slab avalanche unintentionally triggered by a skier. It was medium-sized relative to the path and produced enough destructive force to bury, injure, or kill a person. It started in a layer of faceted crystals 1 to 2 millimeters in size above a fragile melt-freeze crust. The avalanche stepped down to the ground in many places. The avalanche broke 1 to 3 feet deep and about 150 feet wide. It ran about 200 vertical feet (SS-ASu-R3-D2-O/G).

Backcountry Avalanche Forecast

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC) issued a Special Avalanche Advisory for the area around Breckenridge beginning on Friday, December 30, 2022, at 4:30 PM, expiring on Sunday, January 1, 2023, at 5:00 PM.

The CAIC’s forecast on December 31st rated the avalanche danger at CONSIDERABLE (Level 3 of 5) at all elevations. Persistent Slab avalanches with a likelihood of Likely were highlighted on all elevations on northwest, north, northeast, and east-facing aspects and on southeast-facing aspects near and above treeline. The expected avalanche size was Small to Large (up to D2). The summary stated:

A Special Avalanche Advisory is in effect for areas around Berthoud, Loveland, Fremont, and Hoosier Passes for the weekend. Large and dangerous avalanches will be easy to trigger. Traveling in backcountry avalanche terrain requires cautious route finding to stay safe. Avoid travel across or below slopes with a slope angle greater than about 30 degrees.

You can trigger an avalanche that breaks on deeply buried weak snow. The most dangerous slopes are northwest through east to southeast. You can trigger an avalanche from the bottom of a slope or from a distance, so pay attention to steep terrain overhead. You may not see typical signs of instability, like shooting cracks and audible collapsing, before an avalanche breaks.

Weather Summary

The first significant storms of the winter came in mid-November. The Breckenridge ski area recorded 16 inches of snowfall between November 14 and 19. A dry period with mild daytime temperatures and cold nights followed. Towards the end of this dry period, daytime temperatures were above freezing.

From November 26 through December 25, small storms moved through the area. Although there were multi-day breaks in the stormy weather, the Breckenridge ski area picked up another 48 inches of snow. On December 27, there was a shift in the weather pattern as the first in a series of moist Pacific storms began to move through Colorado. The Breckenridge ski area recorded 16 inches of snow between December 27 and December 31st. This period was also very windy, with moderate to strong westerly winds and stronger gusts.

On December 31, the day of the accident, skies were overcast with light snowfall that stopped around 1:00 PM. Daytime temperatures were in the mid to high twenties. Winds at Breckenridge’s Horseshoe Bowl weather station, 2 miles north of the accident site at 11,900 feet, were 10 mph from the east, gusting into the 20s and 30s.

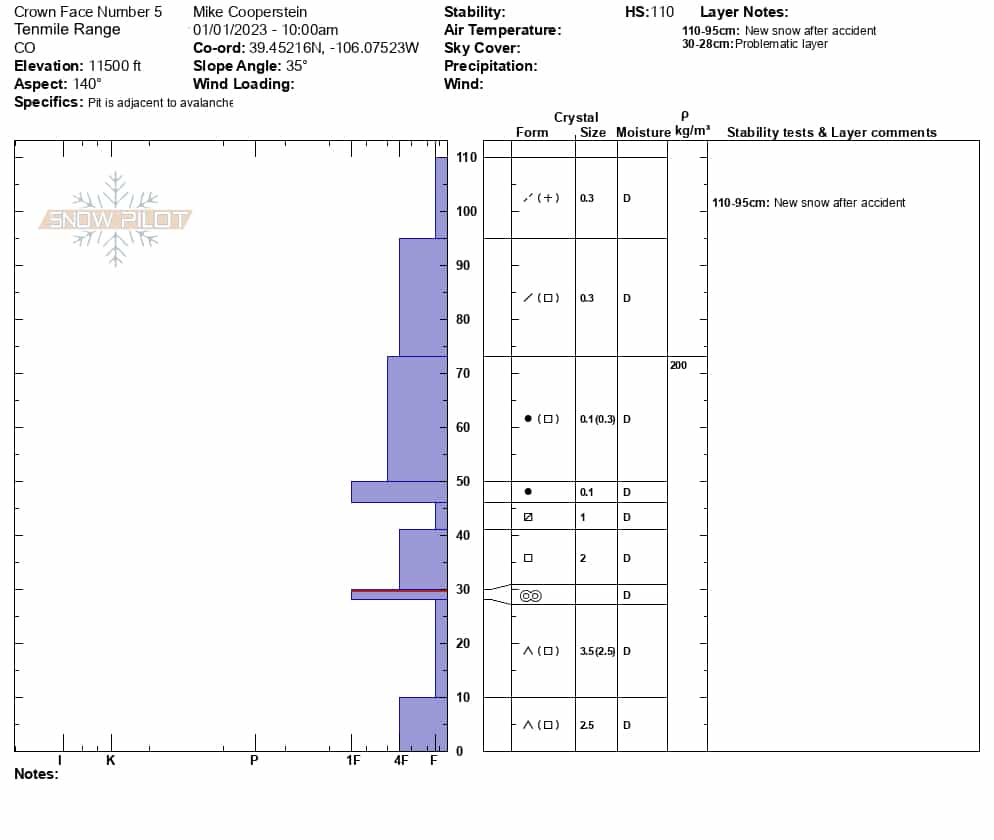

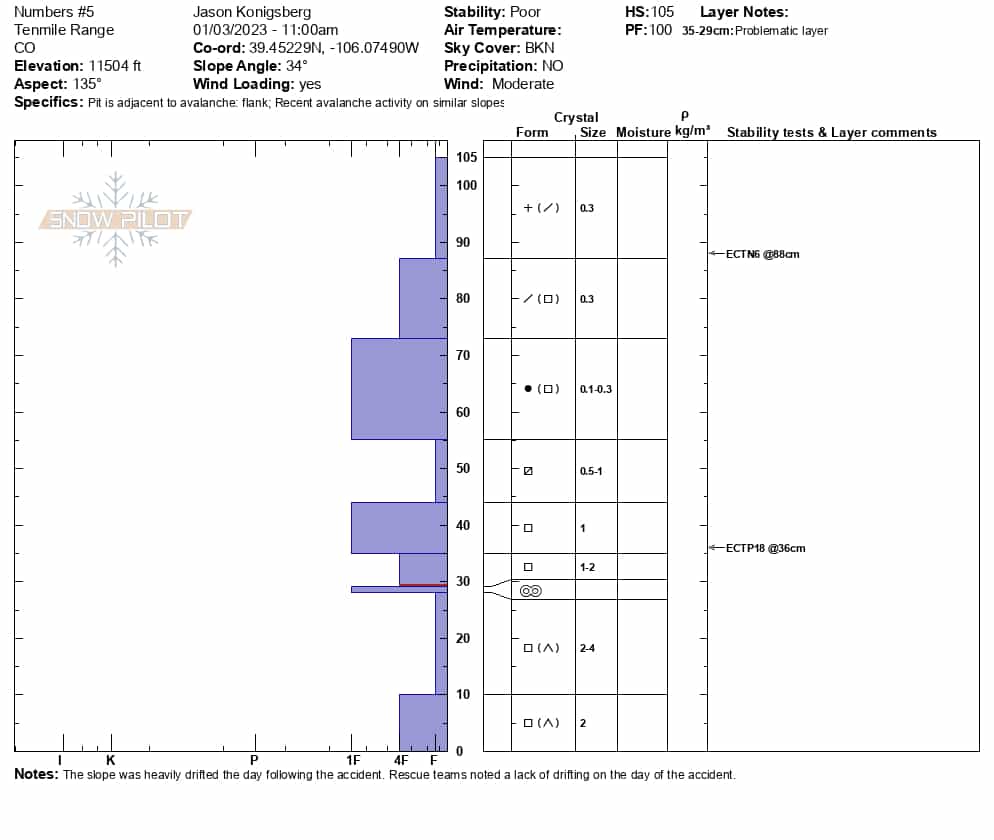

Snowpack Summary

Snowfall from the mid-November storms faceted during dry weather from November 19 to 26. A thin melt-freeze crust formed above these facets on south and east-facing slopes. Snowfall on November 26 buried this crust/facet combination.

Consistent snowfall in December, with several wind events and periods of warm temperatures, formed a cohesive slab of snow above the crust/facet combination. By the end of December, about 60 cm (~2 feet) of cohesive snow was resting on this crust/facet combination.

Events Leading to the Avalanche

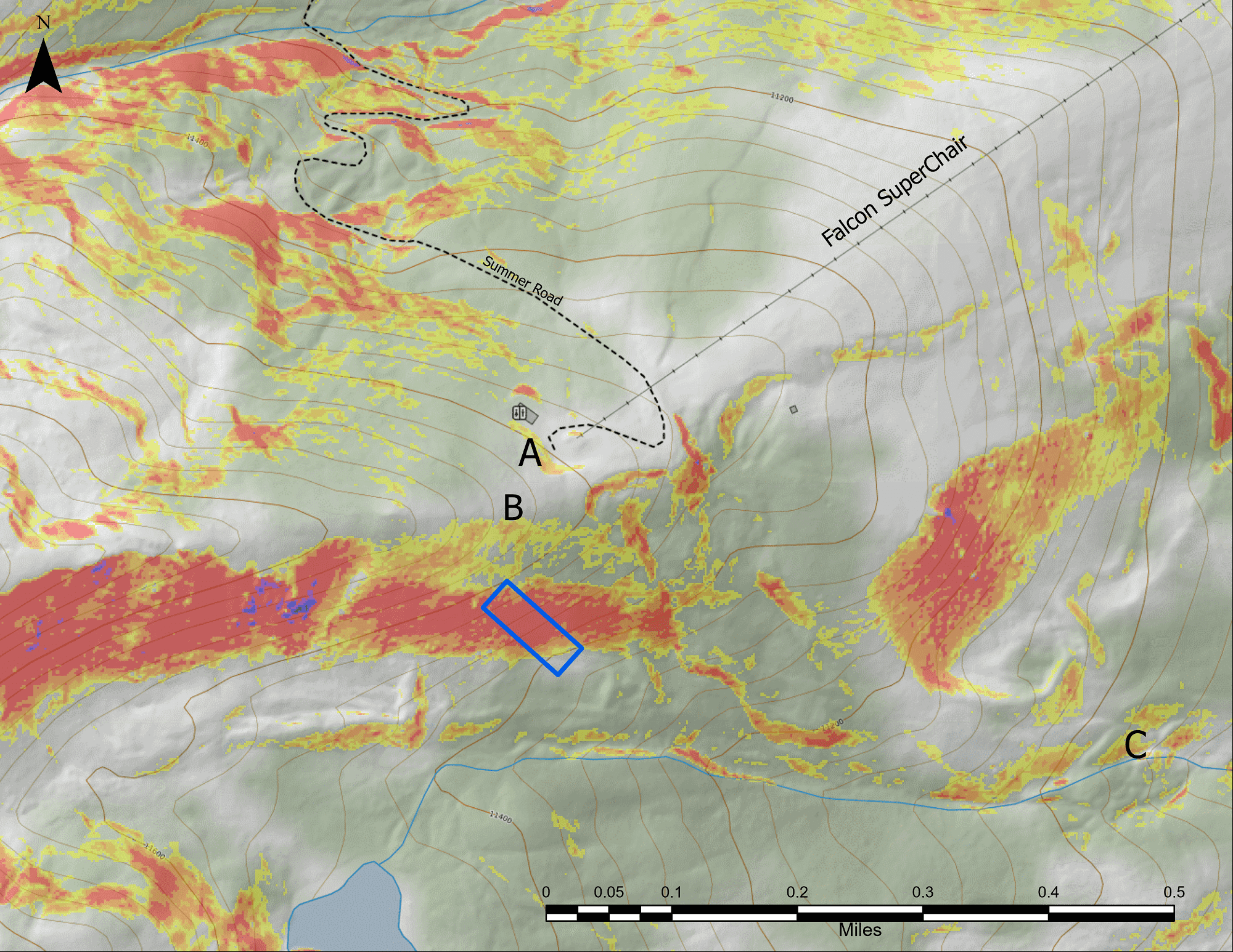

Skiers 1 and 2, an adult son and his father, arrived at the Breckenridge ski area on the morning of December 31, 2022. They made a handful of runs inside the ski area. Around 12:30 PM, they reached the top of the Falcon Superchair and made the short hike to the backcountry access point southwest of the chairlift.

A few other people left the boundary at the same time as Skiers 1 and 2. They all traveled uphill and to the east to an area locally known as the Ballroom. No other riders had ventured into the Numbers. Skiers 1 and 2 walked about 200 feet before putting on their skis and traversing left, to the south, through the trees to the top of an open slope locally known as Number 5. This was the first time they had been in this area.

Skier 1, the son, descended the skier’s right side of Number 5. He stopped about three-quarters of the way down the slope. He sat near a tree to watch Skier 2, his father, descend.

Accident Summary

Skier 2 started his descent. He moved across the slope from the skier’s right edge to the left. He made about ten turns when he triggered the avalanche near the middle of the slope. The avalanche broke well above him.

Skier 2 described the avalanche “like I was riding on a violent wave, and it was hard to stay upright.” The avalanche eventually overtook Skier 2. When the avalanche stopped, his body and face were under the snow (partially buried-critical). He could wiggle his hands above his head where he could see light. He managed to extricate himself from the debris. He estimates the process took him more than 20 minutes.

Skier 2 emerged from the snow near the toe of the avalanche. He could not find any sign of Skier 1. Skier 2 tried to call 911, but there was no cell phone service. He yelled for Skier 1 but heard no reply.

Skier 2 decided that he needed to go back to the ski area for help. He traversed through the trees, yelling for help. There were no other tracks, so he had to break trail through the snow. Two brothers skiing on an inbound run named Flapjack heard Skier 2 in the woods yelling and stopped to see if they could help. Skier 2 informed them that there had been an accident and Skier 1 was missing. One of the brothers waited for Skier 2. The other brother skied to an emergency phone and called the ski patrol at 1:45 PM.

Rescue Summary

After Skier 2 reached the ski run, he skied to the bottom of the Falcon Superchair. Ski patrollers escorted him to the patrol room at the top of the lift. At 2:00 PM, the ski patrol confirmed there was an out-of-bounds avalanche and notified the Summit County Sheriff, who initiated a search and rescue response.

At 2:05 PM, a team of three rescuers from the Breckenridge ski patrol left the ski area to determine the location of the avalanche and find a safe route to access the accident site. They followed the boot pack up the ridge looking for ski tracks going into the Numbers. They identified one set of tracks heading toward Number 5. Another team of three rescuers was dispatched around 2:15 PM. They arrived at the scene of the avalanche first. They searched the avalanche area for a transceiver signal and visible clues but found nothing. They began spot-probing likely burial locations.

The six rescuers started a probe line and systematically searched the debris field. Additional rescuers arrived at the site and remotely triggered a large (D2) avalanche that ran the full length of the Number 4 avalanche path. They were in a safe spot and no one was caught. An avalanche rescue dog team arrived at 2:31 PM and began to search. Rescuers began searching with a RECCO detector around 2:40 PM. The RECCO operator detected a signal. The rescue team probed the area and got a strike at 3:11 PM.

Rescuers dug down and reached Skier 1 about two hours after the avalanche. He was buried about three and a half feet deep on the uphill side of a small tree, face up with his head downhill. He had no signs of life. He was pronounced dead at the scene, and rescuers transported his body back to the ski area. The rescue was completed at 3:46 PM.

Comments

All of the fatal avalanche accidents we investigate are tragic events. We do our best to describe each one to help the people involved, and the community as a whole better understand them. We offer these comments in the hope that they will help people avoid future avalanche accidents.

The avalanche conditions inside and outside of an operating ski area are very different. Ski areas spend a lot of time and effort preparing the slopes within their boundaries for their customers. This includes marking obstacles, grooming runs, and monitoring and reducing the avalanche hazard. Outside of the ski area, none of this work is done. The avalanche conditions are the same just outside of the ski area boundary and deep in the backcountry. It is critical that riders exiting a ski area understand this distinction and are prepared to travel in the backcountry. This includes knowing the current avalanche forecast, carrying avalanche rescue equipment (avalanche transceiver, probe pole, and shovel), and having some avalanche training. This accident is a stark example and tragic reminder of how different avalanche conditions can be in a managed vs natural snowpack. Leaving a ski area through a backcountry access point is the same as entering the backcountry from any other trailhead.

It is a standard avalanche safety practice to expose just one person at a time to any avalanche hazard. The most common way to do this is to travel through avalanche paths or sections of avalanche terrain one at a time. In this case, both Skiers 1 and 2 were on the slope simultaneously, and the avalanche buried both. If you are caught in an avalanche, and your head is under the snow, your only chance of survival is a speedy rescue. In most cases, this rescue needs to come from the members of your group or people close by. In this case, both Skiers 1 and 2 were buried in the avalanche with their heads under the snow, and there was no one close enough to see the avalanche and help them. Fortunately, Skier 2 was on a side of the avalanche where the debris was relatively soft, and he got himself out of the snow. Skier 1 was on the other side of the avalanche debris field and buried in much denser snow. With no equipment or piece of clothing poking out of the snow and without avalanche rescue equipment, Skier 2 had no choice but to go for help. The Breckenridge Ski Patrol, Summit County Search and Rescue Group, and Summit County Sheriff’s Office launched a speedy and efficient response, but most organized rescue efforts arrive too late for a live recovery.

RECCO is a tool that professional rescuers use to locate people buried in avalanche debris. It’s a two-part system: 1) an active detector carried by the rescuer and 2) a passive reflector carried by the user. The RECCO detector emits a directional signal, like the beam of a flashlight. The RECCO reflector bounces the beam back to the receiver so the rescuer can locate a buried person. RECCO reflectors are sewn into certain pieces of outdoor clothing or equipment. Sometimes other electronic devices can act as reflectors. RECCO reflectors are not a replacement for an avalanche transceiver, but they are another way for people to be searchable in a place where rescue organizations like ski patrols and search and rescue groups have a RECCO detector. Backcountry recreationists do not usually carry RECCO detectors.

There was an avalanche involvement in Number 4 on December 19, 2015.