Yesterday the Colorado Avalanche Information Center released its full report from the fatal slide near Aspen Highlands, CO, on March 19th, 2023. The findings can be a learning opportunity for all of us.

The full report is below:

Avalanche Details

|

Number

|

Avalanche

|

Site

|

Avalanche Comments

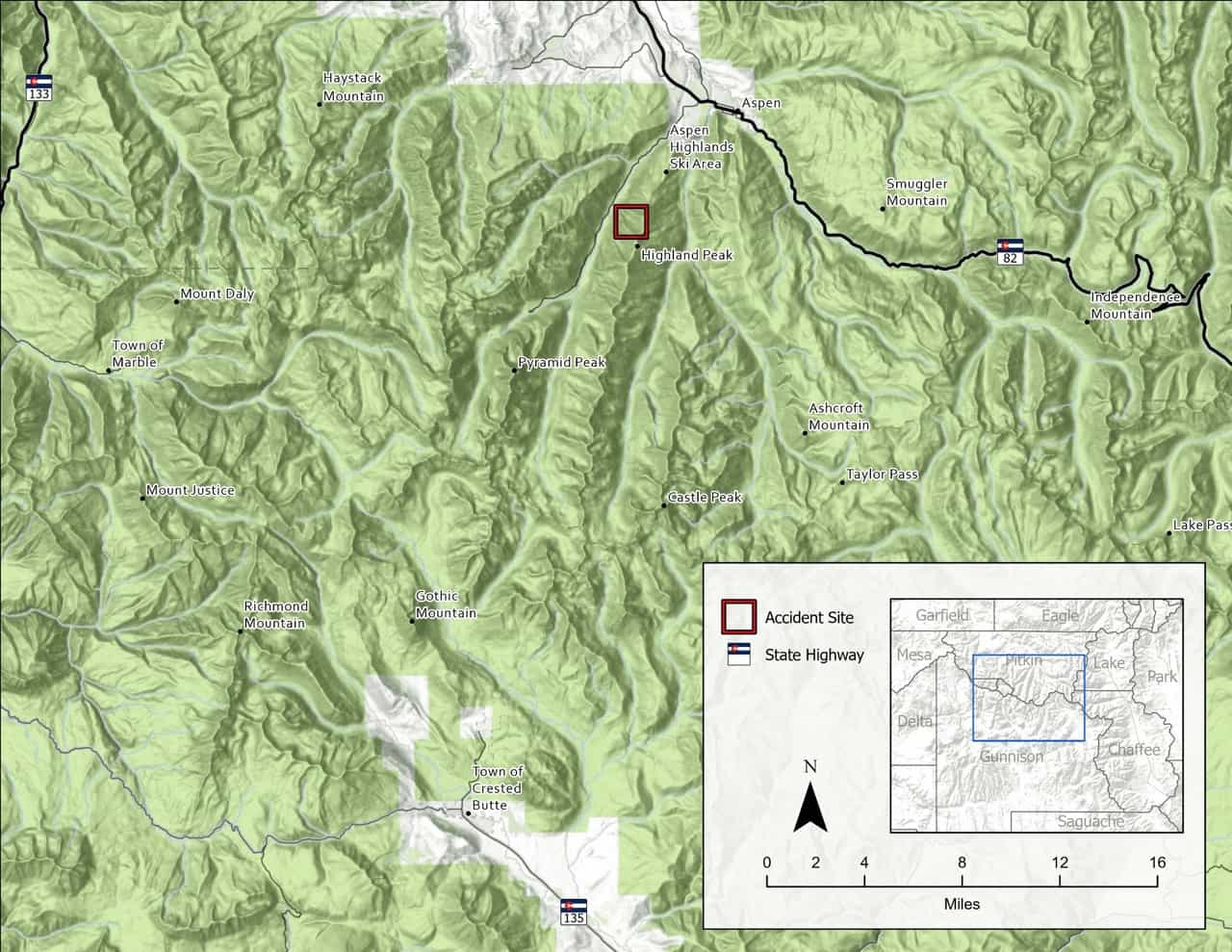

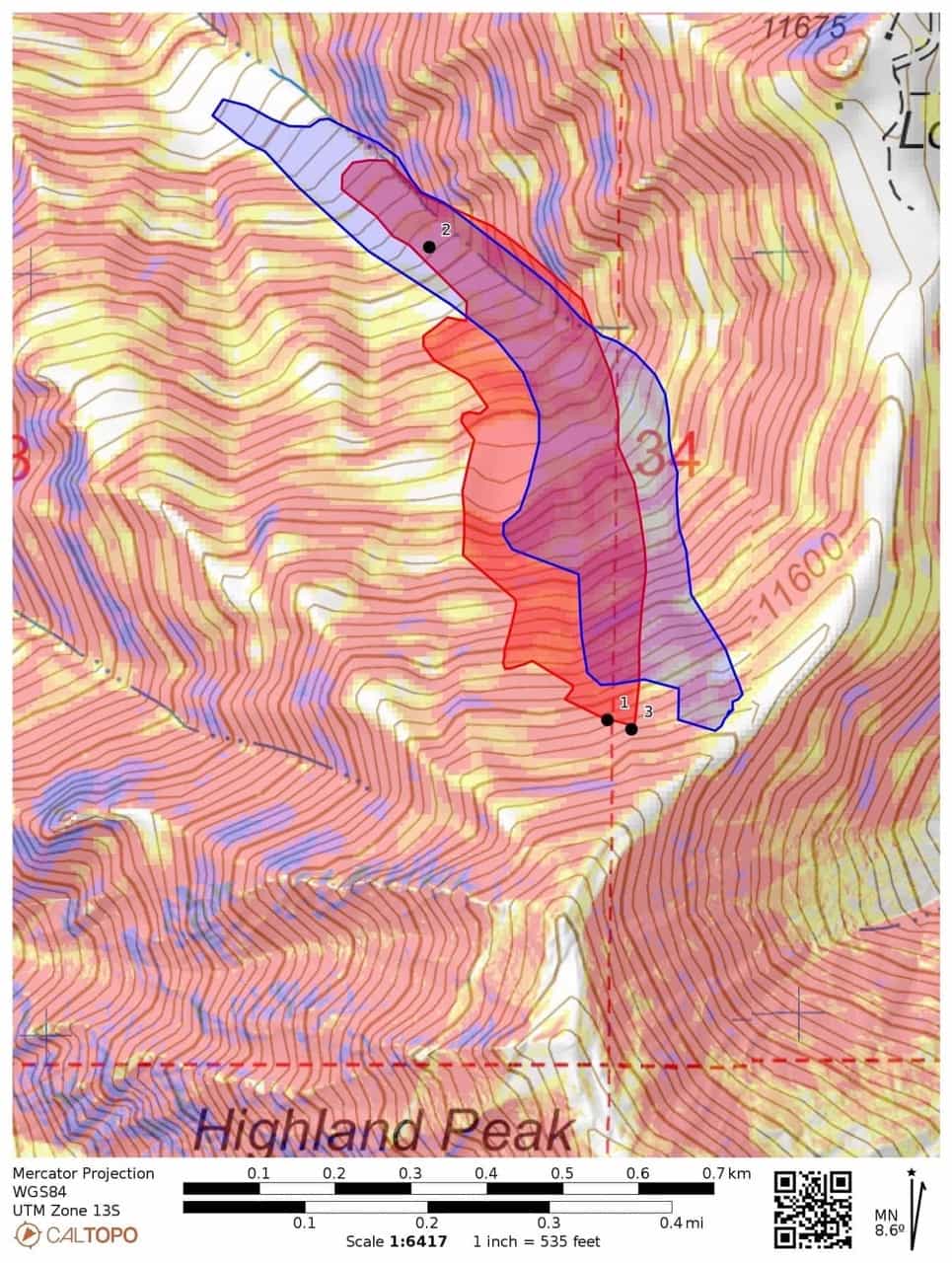

The avalanche occurred in Maroon Bowl, on a near treeline, northwest-facing slope on Highland Peak in an area adjacent to but outside the Aspen Highlands ski area boundary. It was a very large avalanche unintentionally triggered by a group of sidecountry skiers. It was small relative to the path and produced enough destructive force to bury and destroy a car, damage a truck, destroy a wood frame house, or break a few trees. The avalanche broke on a layer of well-developed depth hoar that formed the bottom 50cm of the snowpack (HS-ASu-R2-D3-O). The avalanche broke up to six feet deep, 1000 feet wide, and ran 1500 vertical feet towards Maroon Creek.

Backcountry Avalanche Forecast

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center’s (CAIC) forecast for the area including Maroon Bowl on Highlands Peak for Sunday March 19, 2023, rated the avalanche danger at Moderate (Level 2 of 5) at all elevations. Persistent Slab avalanches with a likelihood of Possible were highlighted on northwest through north to east aspects at all elevations as well as west and southeast aspects near and above the treeline. The summary statement read:

You can trigger a large avalanche that breaks on weak layers buried deep in the snowpack. Although a poor snowpack structure can be found on many slopes, the most dangerous slopes face an easterly direction. This is where recent storm snow sits on buried weak layers and crusts. The only way to deal with this avalanche issue is to avoid steep easterly slopes. You may not get any indication of unstable snow before you trigger a large and dangerous avalanche.

Several large avalanches have been triggered over the last few days in the Marble area. Tragically, on Friday, three backcountry tourers were caught in a very large avalanche and one was buried and killed. You can find a preliminary report on our website. Our deepest condolences to the friends and family of the deceased.

Weather Summary

A series of storms deposited one to three feet of snow throughout the Elk Mountains in late October and early November. This was followed by a two week dry spell with sunny days and cold temperatures.

The snow resumed in late November and the Aspen Highlands ski resort reported near continuous snowfall through March 5. On March 11, after a six day dry spell (the longest dry spell since November), a series of atmospheric river events returned intense snowfall to the Elk Mountains. Aspen Highlands reported 31 inches of dense new snow between March 10 and 19.

The day of the incident was partly cloudy with temperatures between five to 15 degrees Fahrenheit and a southwest wind five to 15 mph gusting in the mid-20s.

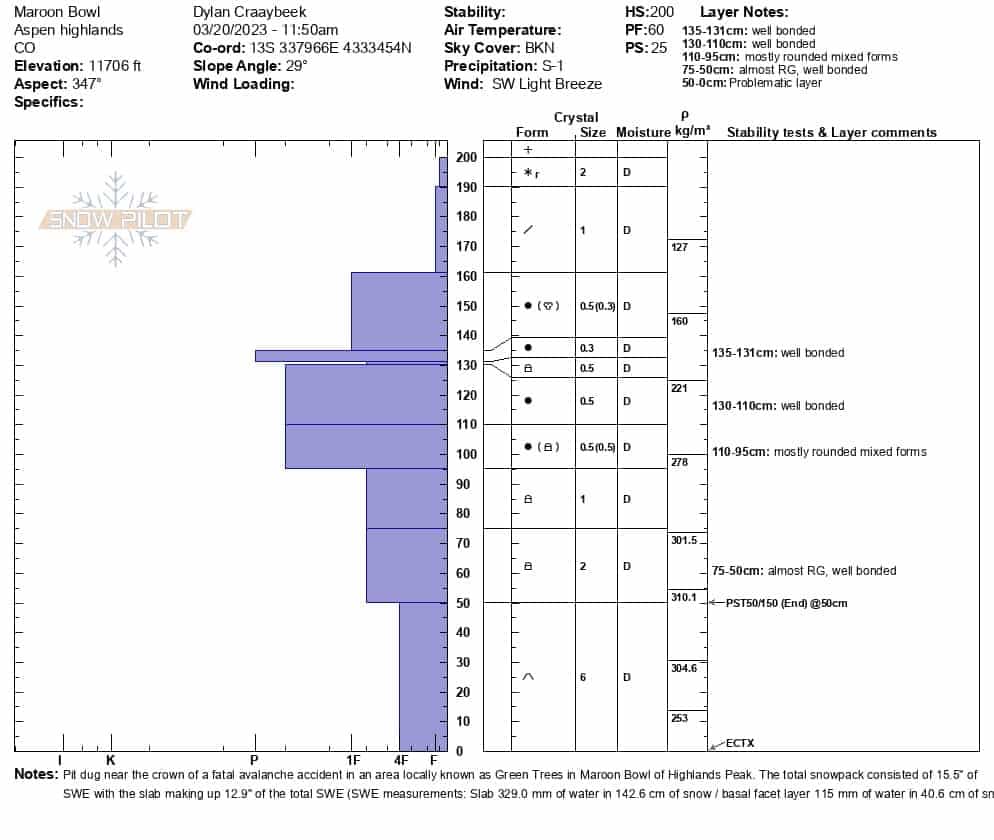

Snowpack Summary

In mid-November, the early season snow melted from most slopes except shady, high-elevation slopes facing northwest, north, and northeast. The snow developed into a thick layer of faceted grains on the shady slopes, becoming the primary weak layer across the eastern Elk Mountains. Consistent snowfall created a deep snowpack, averaging about six feet deep, by the end of February.

Between February 23 and March 8, the CAIC recorded 27 large or very large (D2 or greater) avalanches in the small region between Highlands Ridge and Ashcroft. Many of the avalanches broke in faceted weak layers near the ground. Southwest winds drifting snow into northwest-facing avalanche starting zones was the primary driver of this localized avalanche cycle.

On March 11, Aspen Highlands snow safety teams were conducting avalanche mitigation in Highlands Bowl, in-bounds terrain on the opposite side of the ridgeline from Maroon Bowl. During mitigation, they sympathetically triggered a very large avalanche in Maroon Bowl that broke to the ground.

Events Leading to the Avalanche

Skiers 1, 2, and 3 had skied together in the backcountry for many years. All had avalanche education and carried avalanche safety equipment, including avalanche airbag packs. They were on vacation in the Aspen area and skied for several days at the surrounding ski areas.

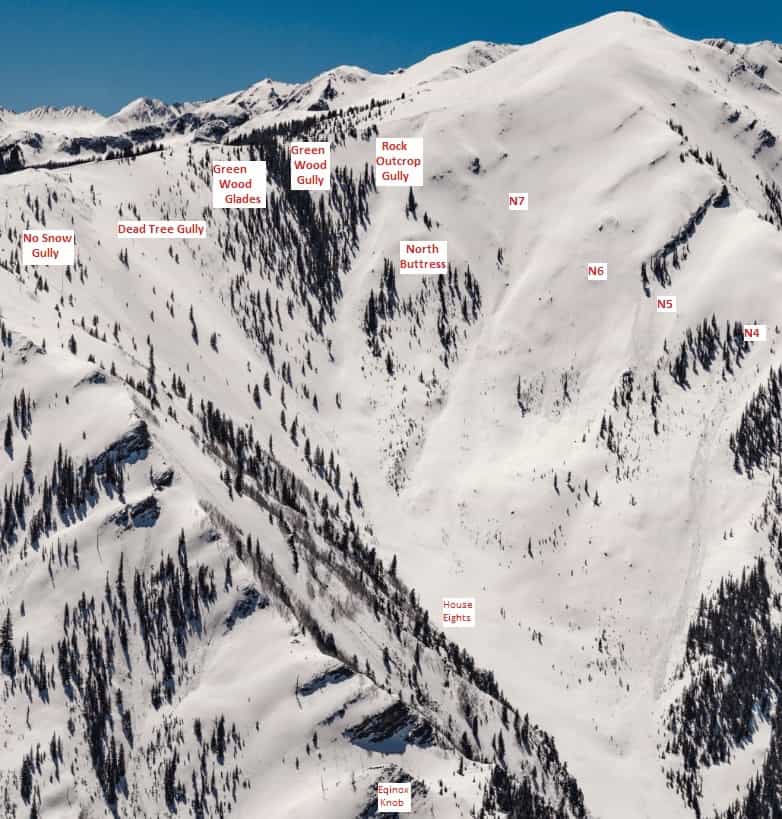

On March 18, the three went to Aspen Highlands to ski in the adjacent backcountry. They skied in-bounds through the morning. In the afternoon, they exited the ski area through a backcounty access point above an area locally called Green Wood Glades. The trio dug a profile through the upper few feet of the snowpack and found no concerning weak layers. They skied down Green Wood Glades. They climbed a steep, north-facing slope locally referred to as N5. They descended N5 to Maroon Creek without incident.

On Sunday, March 19, 2023, Skiers 1, 2, and 3 spent the morning skiing in-bounds at Aspen Highlands. They decided to venture back into Maroon Bowl after lunch. The three discussed the stable conditions they observed the previous day and that cold temperatures and no new snow would not have changed conditions overnight. Skier 2 said he was tired and wanted to ski one descent down to the road. They planned to hike past yesterday’s first descent and make a slightly longer run to Maroon Creek.

The three skiers began hiking up the ridge 12:15 PM. They hiked to the top of a northwest-facing slope locally referred to as N7 and left the ski area. They skied down a short distance and regrouped above a rock band. Skier 1 descended through the rock band and stopped to the skier’s left to watch Skier 2 and 3 descend. Skier 3 waited above the rocks.

Accident Summary

Skier 2 fell forward and began sliding as he skied through the rock band. He released a small amount of surface snow and deployed his avalanche airbag. A large avalanche broke to the ground as Skier 2 slid below the rockband. The fracture line came within a few feet of both Skiers 1 and 3. They watched as the avalanche swept Skier 2 down the slope and out of sight.

Rescue Summary

Skiers 1 and 3 immediately decided that Skier 1 would conduct the companion rescue and Skier 3 would climb back to the ridge and get help from Aspen Highlands ski patrol. Skier 3 called 911 at 1:28 PM, and began hiking back towards the ridge. Skier 1 began to search with his avalanche transceiver.

Ski patrollers witnessed the avalanche from patrol headquarters and responded immediately. They dropped a rope to Skier 3, who was having difficulty climbing to the ridge in deep unsupportable snow. They determined that it was too dangerous for ski patrollers to descend Maroon Bowl, and concentrated their efforts on facilitating emergency response and communication with Skier 1.

Skier 1 detected a transceiver signal after a few minutes of searching. He quickly followed the signal and saw part of Skier 2’s upper body visible on the avalanche debris. Skier 1 wiped a few inches of snow from Skier 2’s face and airway (partial burial-critical) about five minutes after the avalanche released. Skier 2 was unconscious. Skier 1 did not detect breaths or a pulse, cleared space around Skier 2’s torso, and began CPR.

Unable to reach Skier 3 by phone, Skier 1 called 911 at 1:58 PM. He learned that a helicopter was en route and a rescue team was climbing up from Maroon Creek. Skier 1 continued CPR for over an hour. At the advice of rescuers, he ceased resuscitation efforts and concentrated on digging Skier 2 free.

A helicopter from the Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control arrived at 4:36 PM with two rescuers from Mountain Rescue Aspen. They finished extracting Skier 2 from the debris and loaded Skiers 1 and 2 onto the helicopter at 4:42 PM. The two rescuers skied down to Maroon Creek road and responders were out of the field shortly after 5:00PM.

Comments

All of the fatal avalanche accidents we investigate are tragic events. We do our best to describe each accident to help the people involved, and the community as a whole better understand them. We offer the following comments in the hope that they will help people avoid future avalanche accidents.

The three friends had been regularly skiing together in the backcountry for the last 15 years. They all had avalanche rescue equipment and practiced using it regularly. They had taken numerous avalanche courses in Europe, and had been following avalanche conditions in Colorado by reading CAIC avalanche forecasts in the weeks preceding their trip.

They saw and discussed the very large avalanche that ran sympathetically on March 11. They reasoned that the avalanche was old enough and far away enough from the slopes they intended to ski to pose little concern. This assessment underestimated the impact the March 11 avalanche had on the nearby snowpack. The March 11 avalanche fractured very near where they planned to ski, and left dangerous unsupported slabs above and adjacent to the fracture line. They did not recognize they were skiing on to unsupported hangfire from the March 11 avalanche. Note: Hangfire is when an avalanche releases but leaves sections of the slab, above the fracture line, on a slope with a similar aspect and slope angle.

The group dug a snow profile on March 18 in a reasonable location for assessing the snowpack. They only dug through the top few feet of the snowpack and found no concerning layers. Their assessment failed to test the weak layer near the ground. They toured through Green Wood Glades and N5 without consequence (This approach in the same terrain resulted in a fatal avalanche accident in April 2018).

The previous day’s experience boosted their confidence about snowpack stability on N7. They failed to account for the higher chance of triggering avalanches from thinner snowpack areas such as previously avalanched terrain or slopes with exposed rocks. The group descended into such an area the day of the accident, and triggered a very large avalanche from a rocky spot with a shallow snowpack.

Skier 1’s very rapid rescue was impressive. He located and cleared Skier 2’s airway within five minutes of the avalanche. Tragically, this accident demonstrates that rapid response times are not always enough to save someone’s life.

It is extremely fortunate that the avalanche did not kill all three people. The avalanche fractured to within a few feet of both Skiers 1 and 3. Only by sheer chance were they not caught in the avalanche. Careful assessment of stopping points is critical to ensure that no more than one person at a time is exposed to the threat from avalanches.

Media

Video

- A short video of CAIC staff investigating the site on March 20, the avalanche the day after the accident.