You pull back the curtains to an unexpected winter wonderland. Everything is buried. A heavy blanket of fresh powder covers rooftops, vehicles, and the slopes outside your window. There’s a certain mystery to snow days like these that sometimes defy the forecast and keep powder hounds guessing. Sometimes, the culprit behind these massive dumps comes courtesy of one of the atmosphere’s most peculiar wanderers: the cutoff low.

Though rare, cutoff lows are some of the most intriguing players in atmospheric science, bringing wildcards into what might otherwise have been predictable weather. Today, we’re diving deep into the labyrinth of snow science and weather to decode these rogue weather systems, how they form, and why they can sometimes turn an otherwise quiet weather week into an unforgettable winter storm.

What Is a Cutoff Low?

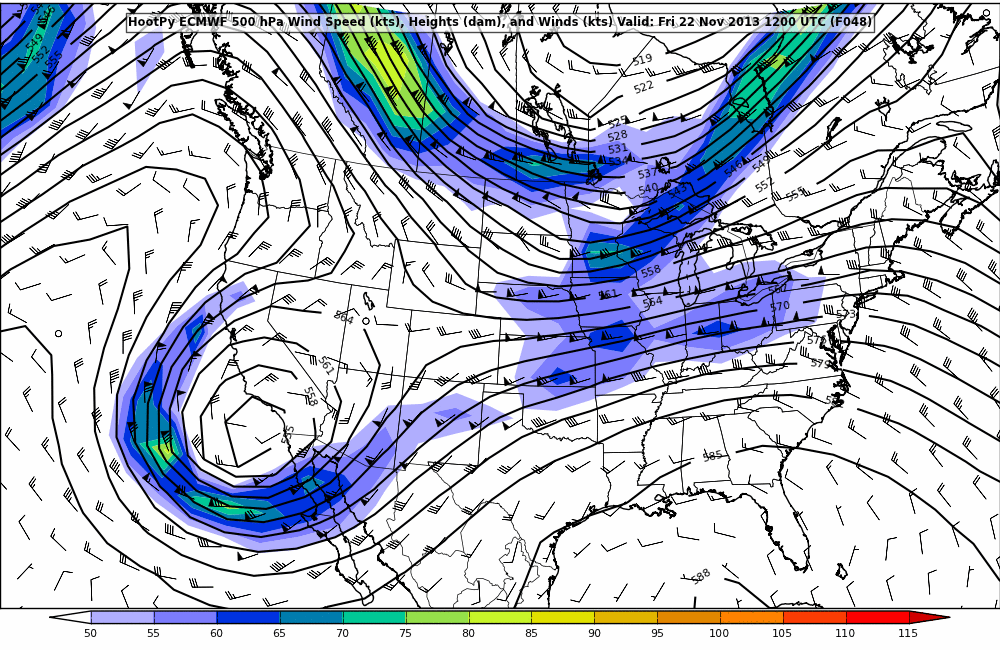

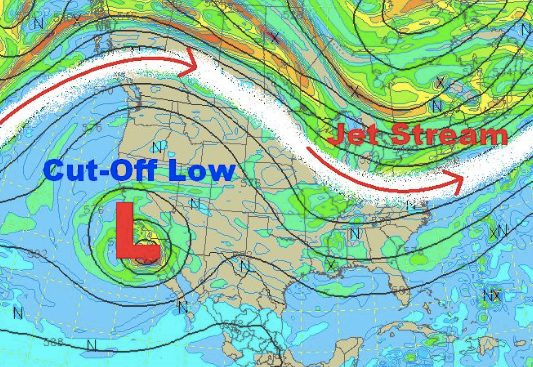

At its core, a cutoff low is exactly what it sounds like—an area of low atmospheric pressure that has broken free from the broader flow of the jet stream. Usually, low-pressure systems move along the jet stream, the fast-moving “highway” in the upper atmosphere that steers weather systems across continents. But every now and then, a pocket of cold air gets left behind. Isolated, untethered, it detaches from this main flow and begins to drift and swirl erratically, following sometimes no discernible path.

Picture it like this: imagine a drop of ink separating from the steady current of a river. While the rest of the water rushes downstream, the ink drop slows, swirls, and meanders on its own, drifting unpredictably. That’s a cutoff low in a nutshell—a weather system set adrift, freed from the natural “rules” imposed by the jet stream.

Cutoff lows are born out of the jet stream’s undulations, a phenomenon known as “Rossby waves.” As these waves bend and weave across the globe, they occasionally dip far enough down to isolate a pocket of frigid air, effectively trapping it below the main flow. When this happens, the jet stream’s forward momentum carries on without it, leaving the newly formed cutoff low spinning in place.

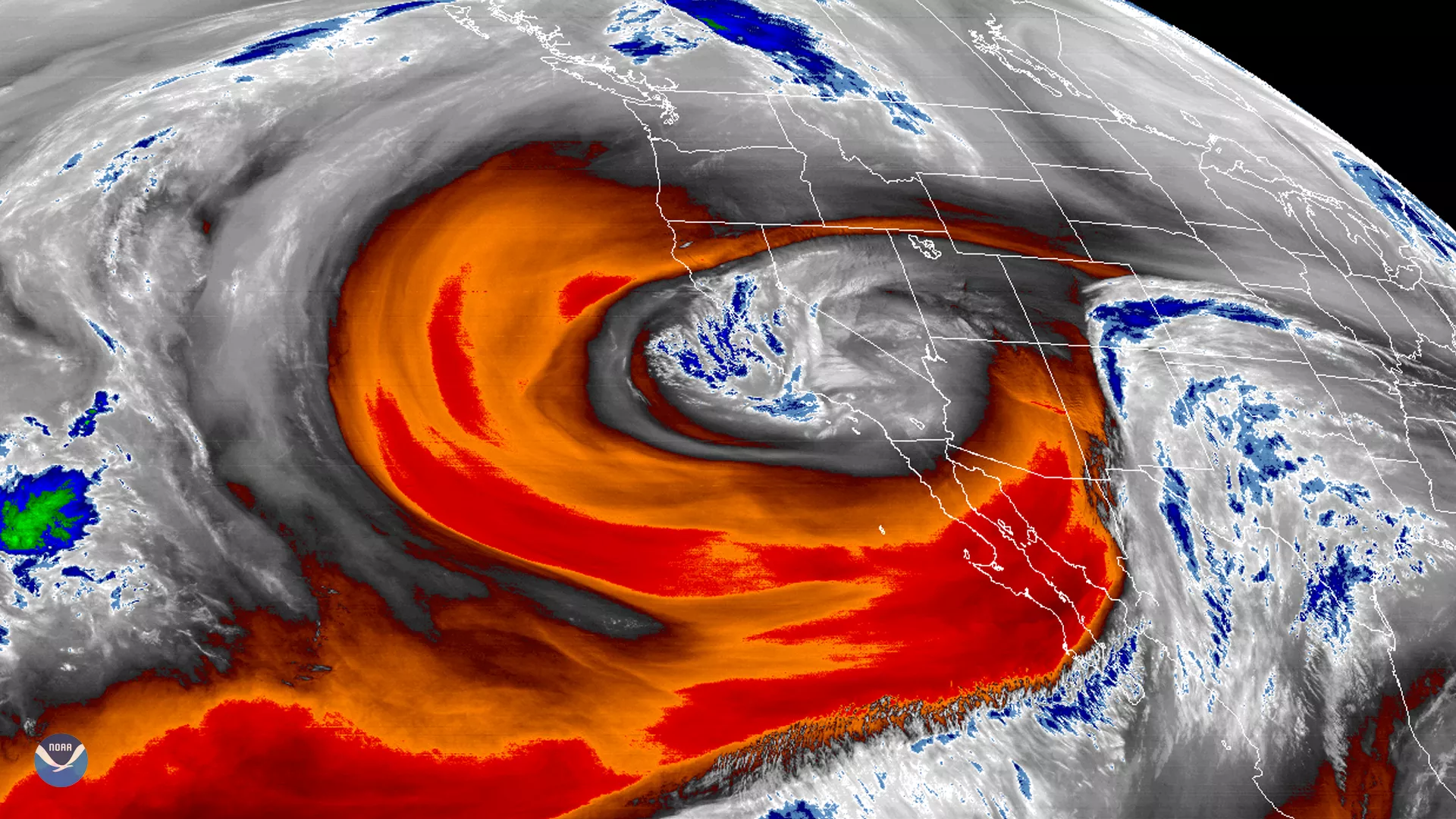

When these renegade systems form, they can linger for days, wandering aimlessly, driven only by local atmospheric conditions. They’re unlike standard low-pressure systems that move swiftly along predetermined routes. If and when a cutoff low strikes the right combination of cold air, moisture, and wind, it can unleash days of unrelenting snowfall on mountainous regions.

Characteristics

One of the defining characteristics of a cutoff low is its snail-like pace. Because it’s not anchored to the swift winds of the jet stream, a cutoff low can remain over a single area for days. This sluggish behavior is one of the key reasons these systems can produce such significant snowfall.

The slow movement allows moisture to build, while the trapped cold air ensures precipitation falls as snow rather than rain. This combination becomes a recipe for prolonged, heavy snowfall over mountainous terrain, such as the Sierra Nevada or the Rockies. The mountains amplify the effect through “orographic lift”—a process where moist air rises, cools, and condenses as it travels uphill, dumping even more snow in concentrated bursts.

For skiers, this slow-and-steady approach can be a blessing. While faster systems might deliver a quick hit of snow and move on, cutoff lows can stretch the snowstorm out over several days, laying down feet of fresh fluff.

The magic of cutoff lows lies in the ingredients they bring together. To produce a classic “massive dump,” you need cold air to keep precipitation falling as snow, ample moisture for consistent cloud formation, and enough time for those clouds to release their full payload. Cutoff lows tick all these boxes.

When these systems stall near mountainous regions, they provide enough time for orographic processes to do their work. Consistent winds direct the moisture into higher elevations, squeezing out snow in amounts that can sometimes feel almost unfair. It’s not uncommon for certain mountain ranges to see multi-day snowstorms with totals reaching three, four, five, or more feet.

The Challenges in Forecasting Cutoff Lows

If cutoff lows are one thing, it’s unpredictable. And for meteorologists, nothing is more frustrating—or exciting. Without the jet stream to guide them, these systems tend to hover, drift, or wobble, changing their target with little warning. Forecast models, which excel at predicting the behavior of larger, more structured systems, often struggle with cutoff lows. That disconnect means snowfall totals can be wildly off-target, leaving skiers and forecasters alike scratching their heads until the snow starts falling.

Because of this, many weather professionals approach cutoff lows with apprehension and excitement. They know the potential is there for something big—but predicting the exact “where” and “when” is often more an exercise in educated guesswork than precision forecasting.

- Related: Machine Learning is Revolutionizing Weather Forecasting: Here’s What That Means for Your Ski Season

Cutoff Lows and Powder Chasing

For skiers, the appearance of a cutoff low on the forecast map can feel like spotting a unicorn. These systems promise legendary skiing conditions, but capitalizing on them requires a willingness to adapt. Flexibility is crucial. Cutoff lows are notorious for delivering snow where it wasn’t expected and skipping over areas that seemed like a sure bet. The key? Keep your travel plans open-ended. Watch the models closely, but don’t rely on them entirely. If you’re willing to go wherever the snow falls, you might find yourself in the middle of one of the season’s best powder days—or weeks—.

Cutoff lows are the rogue artists of the atmosphere, drifting unpredictably and painting landscapes with surprises that no one—meteorologist or skier alike—can fully anticipate. With their unique ability to deliver prolonged, heavy snow, these slow-moving systems are a hidden gem for anyone who thrives on the thrill of the unexpected. So, gear up and keep your plans loose the next time you see one spinning its way into the forecast. These wandering systems might turn a quiet week into the storm cycle of the season—and you’ll want to be ready when they do.