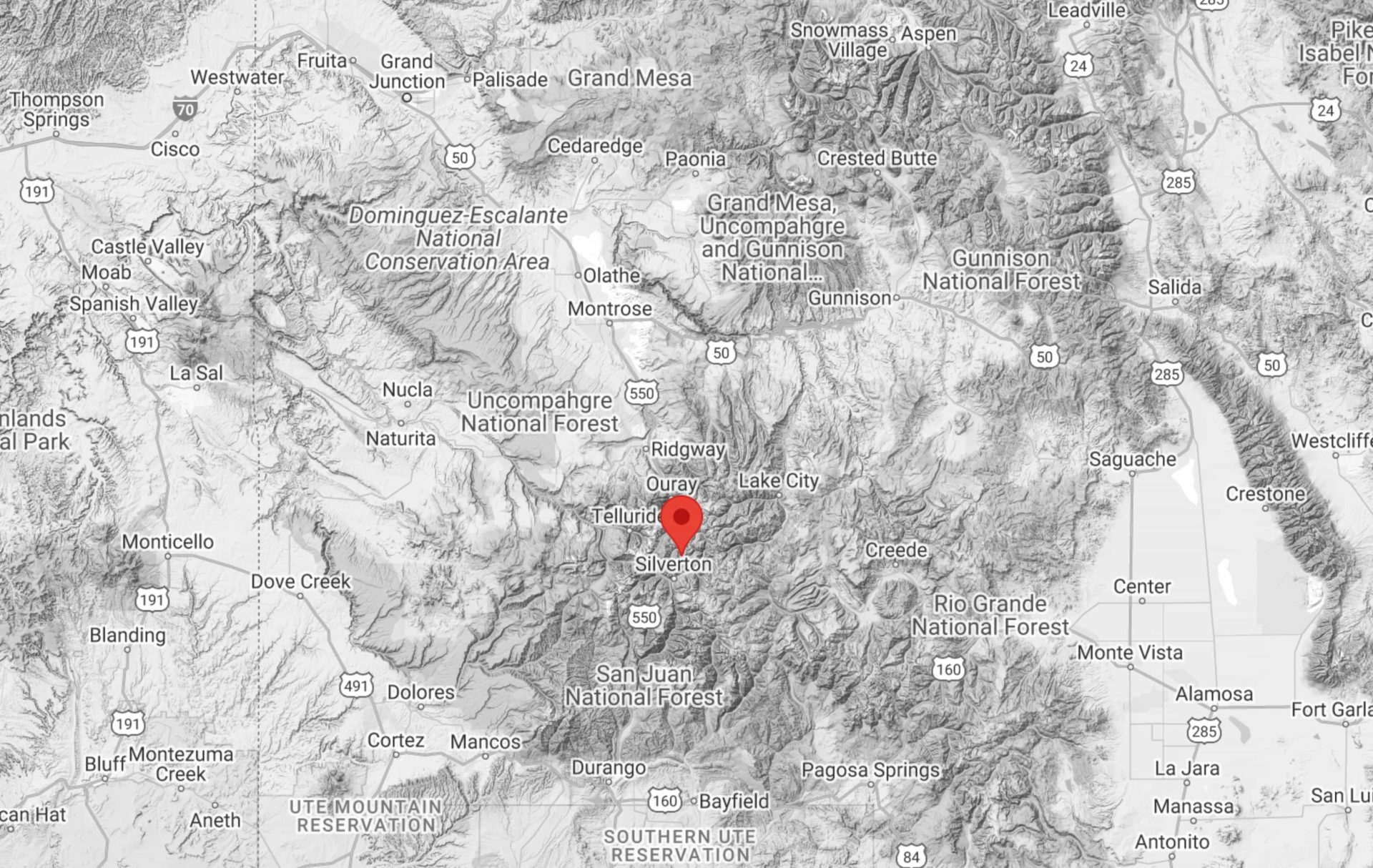

A skier triggered and was briefly caught in an avalanche on Sunday, the first reported human-triggered avalanche of the 2024-25 winter season. The incident occurred in Silverton Mountain, Colorado’s, heli terrain. The area had received almost two feet of fresh snow the previous day.

According to a report on the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC) website, two skiers skinned up Grassy on Silverton Mountain heli terrain. After dropping in, about halfway down, “Skier 1 dipped over convex rollover and saw cracking behind with moving snow. Skier 1 carried speed and skied out of small slide. Skier 2 came to the edge of a convex rollover and triggered a secondary slide over the top of the first. Both skiers skied out safe.”

“Observation Summary

Minor whumphing and cracking was observed on skin track with noticeable difference in snow structure from temperature variation through storm. Two skiers skied north facing ridge. Near Silverton Mtn’s grassy run. Half way down skier 1 dipped over convex rollover and saw cracking behind with moving snow. Skier 1 carried speed and skied out of small slide. Skier 2 came to edge of convex rollover and triggered secondary slide over the top of the first. Both skiers skied out safe.

Route Description

Skinned up Grassy on Silverton Mtn heli terrain. Skied ridge to the north on north to northwest facing slope.”

– CAIC Report

A social post by the CAIC states that “over the past 10 seasons, Colorado has averaged one to two people caught in avalanches in October. Nearly every fall, avalanches catch eager riders and late-season hikers off-guard. Hunters traveling through the high country need to exercise caution on steep, snow-covered terrain. Please be thinking about avalanches if you visit steep slopes in the high country, especially in the Southern Mountains.”

View this post on Instagram

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center released this early-season snow update on its blog a few years ago, which still holds true today. The message is one of warning; big early-season snowfall will affect the layers of snow that will fall on top of this one for the rest of this coming winter season.

CAIC: Early Season Snow

By Brian Lazar and Blase Reardon/Colorado Avalanche Information Center

Fall snow in the mountains – white snow bannered between blue sky and golden aspens. What to make of it? Maybe you hear people bemoaning it as a sign that their biking, climbing, fishing, or gardening seasons are coming to an end. Maybe you hear others extolling it as the promise of a powder-filled winter ahead. Maybe you hear grizzled veterans grumbling that it’s too early and we’re on the road to developing our first unpredictable and potentially dangerous weak layer. Let’s consider that last response and outline some tips on how to deal with that issue.

The fall snow is shallow. That’s its most significant feature. It’s susceptible to melting or weakening, and both processes can have long-term effects on snowpack development and avalanche conditions as the winter progresses. The outcomes depend on future weather.

Melting:

A combination of radiation and heat can melt the early-season snow. Sunny slopes are the first to melt off. If temperatures are warm enough, even shady slopes can melt back to bare ground. A prolonged spell of sunny, warm weather will leave slopes (especially those receiving direct sun) bare of snow or dotted with thin, discontinuous snow patches. This would be a good thing from an avalanche perspective. It would mean subsequent snowfall will be falling on mostly bare ground, without preserving any weak layers at the bottom of the snowpack.

Weakening:

High-elevation shaded slopes aren’t as impacted by radiation and often don’t warm enough to melt snow. On these slopes, the thin snow cover lingers. Temperature gradients – in this case, the difference in temperature between the ground and the snow surface – can be very high. The temperature near the ground hovers near freezing. On the snow surface, it’s generally colder, sometimes much colder. High temperature gradients promote faceting of the snow grains. With time, this thin layer of early-season snow can change into a weak layer of large-grained facets, a layer that collapses when sufficiently loaded. That weak layer will be at the base of any snowpack that accumulates above it. That’s a bad thing.

Some of both:

If the radiation and heat aren’t sustained, they might leave just a crust on the surface of a shallow snowpack. Crusts near the base of the snowpack are notorious for producing thin layers of facets that can persist for long periods. That means ongoing Persistent Slab avalanche problems if they’re buried. Some of our worst years for Deep Persistent Slab avalanches occurred when early-season snow first faceted and then melted just enough to cap the basal facets (depth hoar) with a thin crust. Neither of these scenarios is great for our avalanche future.

So, what’s a snow-lover to do at this point? Monitor the weather and snowpack from here on out. Below are some things to watch:

- Snowline elevation: Put a number on the lowest elevation at which you see snow. Find some markers on a slope you can view regularly, compare them to a topographic map, and check the snowline against those markers. Once snow starts accumulating, you’ll know the elevation above which you need to factor basal facets into your assessments. Or conversely, the elevation below which you don’t.

- Aspects: Be very conscious of the aspect of the slopes where you do and don’t see snow. Use an online mapping tool or a compass to verify your impressions. Being able to differentiate slopes by aspect will again help you include basal facets in your assessments when they’re likely to be present. And deemphasize them when they’re not.

- Snow surface: You’ll need firsthand info to determine whether a crust/ facet combination is developing. That can be opportunistic – checking for it if you are up high or asking people who have been – or planned.

Images of your favorite backcountry areas can serve as great references later. The most useful images are those taken just before the season’s snow accumulates when you can see the distribution of any persistent old snow. Because it’s hard to time that, take images whenever good weather allows.

These practices are focused on determining the distribution of potential weak layers. They don’t tell us much about the actual layers. That we can learn once winter hits in earnest. For now, think “where.”

At this point, we’re hoping for one of a couple of scenarios:

- The snow on the ground now melts away back to bare ground. That way, we could start from scratch when we’re more likely to get consistent snowfall.

- Bury this early season snow with more snow; lots of it and fast! Once we have snow on the ground that is likely to stick around, the more quickly and deeper we can accumulate more snow, the better in the long run. We’re hoping for a snowpack deep enough that temperature gradients aren’t high enough to promote faceting/weakening of the snow on the ground.

Many places that picked up more than 1 or 2 feet of snow in early October now have enough snow to make scenario 1 unlikely. Scenario 2 doesn’t look great either with the mid-range forecasts. That leaves us hoping we don’t cap our currently faceting snowpack with a crust. It’s not the best way to start, but it’s not the worst (yet).