74-year-old Jimmy Petterson might be a traditional skier, but he does not ski in traditional places. In 2010, he went on an expedition to Venezuela to ski 16,207-foot Pico Humboldt in the Venezuelan Andes. It was late October when he arrived in the university city of Merida of about 310,000 people, although it did seem much smaller. Narrow cobblestone streets wound their way through the easy-to-get-around historic center where colorful colonial-era buildings still stood, their weathered facades bearing witness to a long-enduring, often bloody history of Spanish conquest. When Petterson visited Merida, he saw vibrant markets overflowing with assorted fruits and vegetables, their hues mirroring the kaleidoscope of cultures that call the town home. Aromas of freshly ground coffee wafted from quaint cafes tucked into dusty alleyways, smelling extra potent in the thin mountain air. He noticed students from the renowned university going about their daily lives, their laughter and chatter echoing through the city’s tight corridors, blending with the melodies of street musicians—one of his previous occupations.

At the apex of the Venezuelan Andes, Merida sits in the long shadows of towering rocky, treeless peaks. It’s a friendly city cradled by clear, crystalline streams that feed into rivers that have carved away deep, mile-wide valleys over the course of millennia. The Lonely Planet described Merida as “an affluent Andean city with a youthful energy and a robust arts scene.” But Petterson didn’t go there in search of the arts or nightlife. He came instead with only one purpose in mind: to ski in Venezuela, a country that lies only eight degrees above the equator. This is a nation that most people would never expect to have snow, let alone good skiing. Yet Petterson skied there, arcing turns down a scenic and steep mountainside in a place where most of the local inhabitants know as much about skiing as they do space travel.

Skiing and mountaineering are in Petterson’s blood. His mother was a refugee of Hitler’s Austria who came over to the U.S. at age 17 and became the first female certified ski instructor in California. Her uncle was Paul Preuss, born in 1886 and considered the father of free climbing, whom legendary climber Reinhold Messner has mentioned in several of his books and said was one of his biggest inspirations. He was a man who pioneered free climbing in the Alps only to die doing what he loved at the ripe age of 27. So it doesn’t come as a surprise that Petterson’s parents put him on skis at age two. Whether they meant to or not, they instilled in him a love for the mountains and adventure from an extremely young age. This longing for adventure from boyhood onward only grew, eventually inspiring his famous publications Skiing Around The World, Volumes I and II, in which Petterson does exactly that.

After graduating high school, Petterson went to college to study history at USC. He wanted to be a history teacher. Upon graduation in 1972, Petterson decided he’d leave Southern California to spend a winter in the Alps before returning and settling into a role as a teacher. He traveled to Saalbach, the biggest interconnected ski region in the Austrian Alps, and at age 23, he got a job as a ski instructor. That “one season in Saalbach” turned into five. He eventually returned to California to work as a history teacher for one year, but it didn’t stick. Very soon after, he went straight back to the Alps. For Petterson, the gears that would operate the machine for traveling and skiing the world’s most obscure destinations were slowly spinning.

“I did go back to Los Angeles and work a year as a history teacher and that sort of solidified that it was much more fun being a ski bum than a history teacher,” Petterson told me. “And after that, I pretty much never looked back. I started going back to the Alps every season.”

From 1973 to the mid-80s, Petterson worked three winters as a ski instructor in Austria and later as a singer and entertainer while supporting himself as a street musician in the Nordic countries over the summers. At the end of April, he would depart the Alps each year and play music for passersbys in Oslo, Stavanger, Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Helsinki for much of the summer. Come September, he returned to LA to substitute teach, an extremely thankless task but one that allowed him to depart each winter as soon as the snow started flying. Then, in 1985, upon a chance meeting with the editor of the Finnish ski magazine at a friend’s wedding, he talked the editor into giving him a phony letter claiming that he was a ski journalist. With this letter of introduction, Petterson hoped to score some free lift tickets on a trip to Chile and Argentina. When the South American ski resorts comped Petterson free hotel rooms, meals, and lift passes, he developed a guilty conscience. He loaded some slide film into an old Russian Zorki camera and made his first attempt at journalism.

After returning home, Petterson hacked out some descriptions of his adventures on his mother’s old typewriter and sold the articles and photos to the Finnish magazine along with publications in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. He had become a published writer, officially beginning his career as a journalist. From then on, he was not only legit but also hooked on traveling the world in search of fresh powder turns. The desire to seek out rare places that are more “organic,” according to Petterson, is what eventually inspired him to write the first volume of Skiing Around the World.

“I just liked the vibe. As time went on and some of these large, famous ski areas became more and more commercial, the contrast got even bigger. To be honest, you can go to places like Iran—fantastic snow, fantastic skiing, the nicest people you will ever meet—and there’s nobody on the mountain! You can ski for a week and still be making first tracks. That’s a big difference between the rat race of trying to get first tracks in the Vail Backbowls or at Alta. That was very much an incentive in a way.”

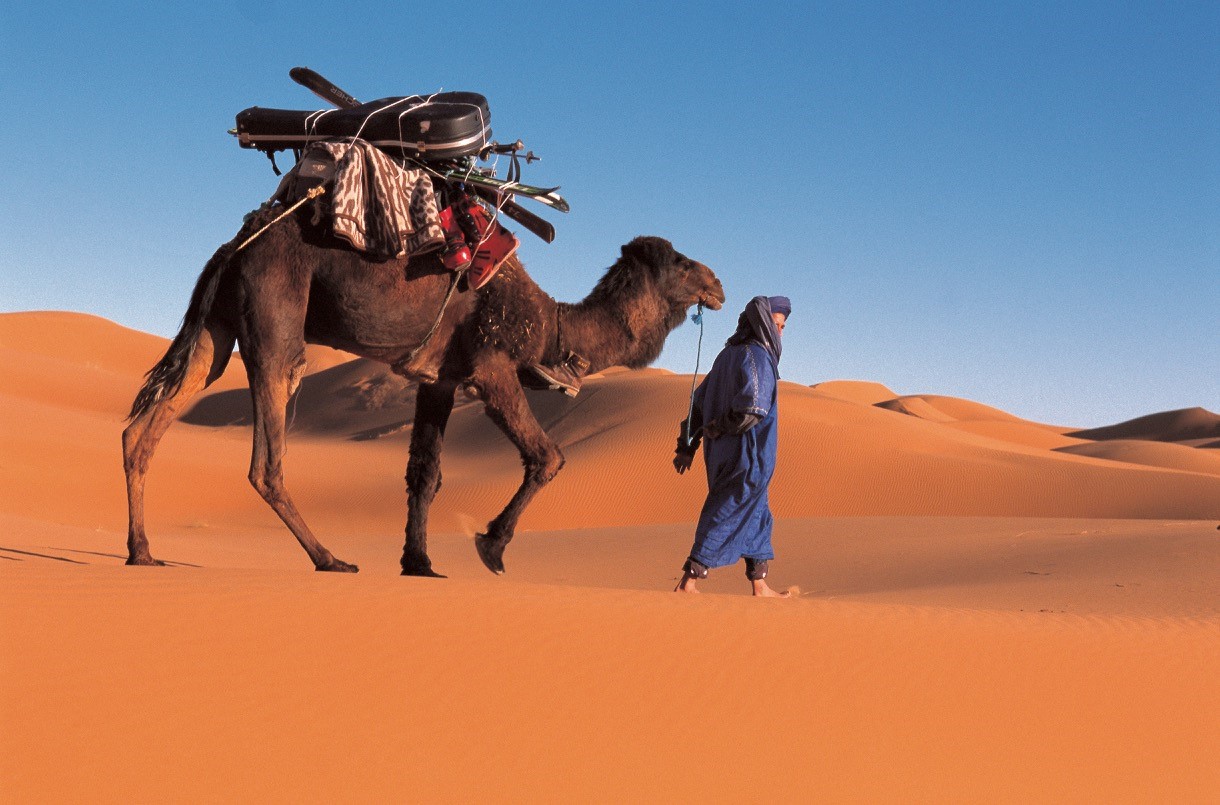

Antarctica. India. Bolivia. North Korea. Mongolia. Uganda. The list goes on. Petterson skied what sounded to me like everywhere, with some places more adventurous than others. Take Uganda, for example, where Petterson skied roughly at 16,000 feet on the Margherita Glacier, the third-highest point in Africa and one of the continent’s only glacial bodies. It took six days of trekking to get to the snowline, and once at the top of the ski descent, there were only about 20 to 25 turns before Petterson had to trek back down. Then there’s Venezuela, where he had to trek through the jungle for days on both the ascent and descent from the peak. That’s not even factoring in the weather, which can be extremely finicky in those remote alpine environments that are close to the equator.

“You’re going through these different climate zones and you have these really interesting and unusual plants that only grow a few places in the world,” Petterson said. “You’re down in rainforest in the beginning, like in Uganda and Venezuela, then you get above the treeline and have some strange-looking vegetation, and then after a while there’s nothing growing anymore. Then you’re getting into the high alpine which is rock and snow. It’s a wonderful, wonderful experience. You must be lucky with weather, of course, because those kind of places usually have a microclimate that is not very hospitable. We got lucky both times.”

As I was picking Petterson’s brain about his travels, I wanted to ask him about skiing in one of the most exotic places I could think of, and the Kamchatka Peninsula on the far eastern side of Russia came to mind.

“I have also skied in Kamchatka on some small lifts and with the chopper,” he wrote me in an email. “That was indeed great. We had mostly corn (not powder) as I was there in early May, but it was so beautiful. Skiing from the top of volcanoes directly down to the Pacific Ocean. Then a picnic on the beach for lunch and I couldn’t resist going for a dip in the Pacific. It was cold, but what the hell, you only live once. We also sometimes finished the day skiing down to a hot spring, where we had a beer and a soak in the warm water. Amazing. That has a chapter in Volume 2.”

Of all the places he’s traveled and skied, Petterson told me North Korea was among the most interesting. He said the skiing wasn’t great, but it was an extremely unique place to travel and ski.

“Many people ask me, ‘Wow, North Korea! How did you get in there?’ But in actual fact, it’s easier to get a visa to North Korea than it is to the United States. You go online, you put in your name and your passport, and there you go.”

But when you do get to North Korea, you can only travel with the official North Korean travel agency, similar to how it was for him visiting China way back in 1979 when it first opened to tourism, Petterson says. The government does this to prevent travelers from interacting with ordinary North Korean citizens as a means to hide the truth about how bad daily life is for them. Visitors stay in specific hotels only for foreigners and must stick to a mandatory travel itinerary drafted by the North Korean travel agency. You see the historical sights they want you to see, you go to the locations that they want you to go—but not the ones they don’t. Still, Petterson did have a few chances to interact with several normal citizens while he was in North Korea, including a group of school children and a soldier in the Demilitarized Zone, who were all open, caring, and sweet people who very much appreciated the opportunity to speak with a foreigner. Those were the moments that stood out for him the most.

Petterson’s trips—they weren’t all about the skiing or the adventure. They were also about the culture. As a journalist, Petterson always looked for an interesting travel angle. “Sometimes, you don’t know what that’s going to be until you get there,” he said. His adventures weren’t only for the slopes; they were about engaging with diverse communities and traditions, enriching his understanding of the world in unexpected ways. Many places he went were not necessarily the most stable politically, with questionable government regimes and often prevalent corruption. But governments are not a good example of a country’s people, Petterson says. “People are what make travel. The poorer the people are, the more hospitable they are. They have nothing and still share their last piece of yak butter with you.”

Jimmy Petterson has left behind a legacy in both volumes of Skiing Around The World that portrays the boundless beauty of this world—one in which human beings play a large role. The books are full of so many priceless ski descents and commentaries on the inspiring people of each region. With Skiing Around The World, Petterson shows us that life’s greatest adventures are still waiting to be discovered and are often just beyond the next ridge or valley. The story of his life that he shared with me is like a tasteful tapestry woven with threads of snow, adventure, and exploration. It speaks for itself upon meeting him when you see the light glimmering in his eyes from having lived such a storied life, much of which is documented in his books. However, it’s not only in the tracks he’s carved across virgin powder that’s etched a profound impact on the skiing community. From the icy slopes of a Ugandan glacier to the sun-kissed peaks of Greece and many, many more exotic ski locales, Petterson’s books serve as windows into the soul of a skier who has dared greatly to traverse this remarkable world in search of the organic skiing experience. “Skiing should be adventurous,” Petterson says. And you don’t necessarily need to go to the other side of the world to find that adventure, either. Truly, anywhere that’s new to you will do.

To purchase a copy of Skiing Around The World, Volumes I and II, visit Jimmy Petterson’s website. Petterson has also written a novel called Coming of Age, produced some CDs with his Father and Son Band, and hosted a TV series called Raider of the Lost Snow. All items are available on his website.

Incredible story and life adventure, Jim is a true human and he is always looking at the bright side of life, I’m happy to know him and love all his stories from all over the world and his songs are always in my head. You must listen/ look to his shows about Rock, Snow and fantastic pics from our planet.