With several US and European ski resorts reaching altitudes above 10,000 feet, altitude sickness is not an unknown factor to the readers here at Snowbrains. It is, however, less commonly known that a serious form of altitude sickness, known as High-Altitude Pulmonary Edema, can strike even at moderate high-altitudes from about 8,000 feet (or 2,440m) and does not just afflict those climbing the Himalayas or other high-altitudes above 20,000 feet.

Rapid ascents or failure to sufficiently acclimatise can lead to altitude sickness, which commonly presents in three forms:

- acute mountain sickness (AMS)

- high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE)

- high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE).

The reason HAPE becomes fatal is the sudden deterioration from mild symptoms to an acute lack of oxygen in the blood. In the past, HAPE has often been misdiagnosed as pneumonia as it presents with similar symptoms. It was first documented as “altitude induced pulmonary edema” in 1960 in the New England Journal of Medicine by Dr. Charles Houston, an Aspen-based GP and avid climber. He came to this diagnosis after treating a sick skier in the Aspen mountains who did not respond to antibiotics, for what he had initially considered to be pneumonia.

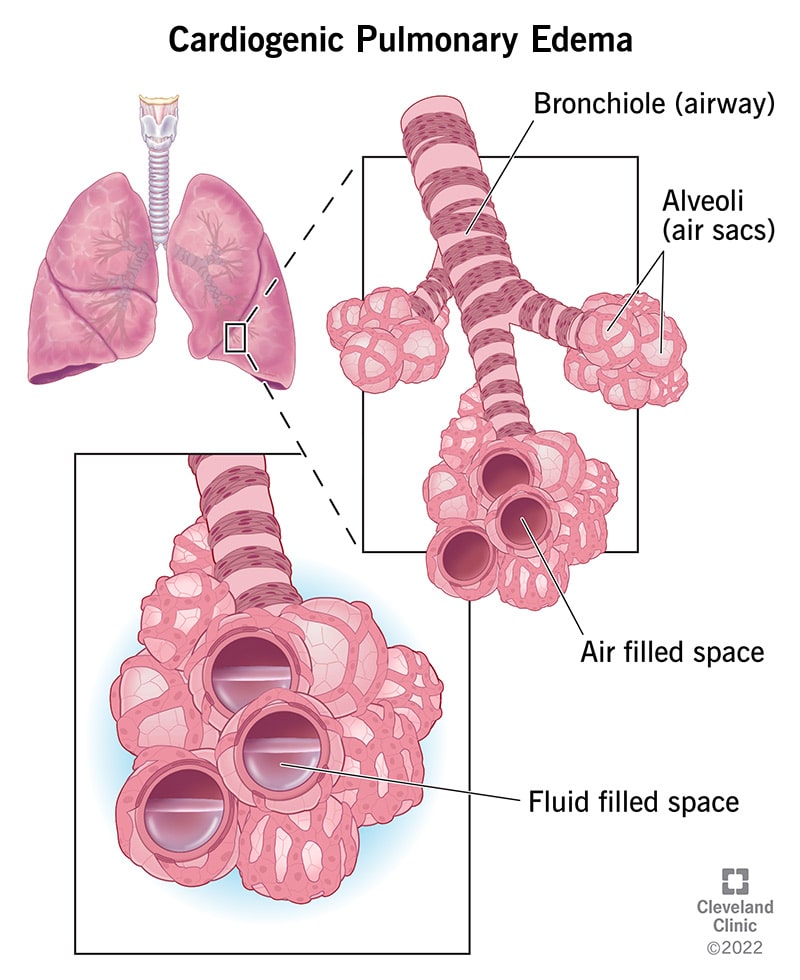

Know the signs: HAPE is a fluid build-up in the lungs and typically presents after 2-5 days of arrival at high-altitude with a cough, shortness of breath and low energy levels. If left untreated, it can progress with symptoms worsening to include a crackling in the chest and coughing up pink frothy sputum. Unfortunately, early symptoms are often dismissed until the situation becomes precarious. HAPE does not respond to antibiotics. The only treatment is a rapid descent to about 1,000 ft or if this is impossible, the use of a portable hyperbaric chamber combined with high flow oxygen. What kills most climbers is not realising the severity of the situation until the lungs fail and they are unable to descend. HAPE has a 50% mortality rate if left untreated.

The incidence of HAPE in visitors to ski resorts is estimated to only be 0.01-0.1%. The risk increases to around 4% for hikers and climbers in the European Alps and the Himalayas who ascend more than 2,000 feet (600m) per day.

What is scary about HAPE is that it strikes fit, young people. It is not an affliction of the weak or unfit. Thor actor Chris Hemsworth had to be evacuated from the Himalayas in 2016 from 13,000 feet, recounting in an interview with Jimmy Kimmel how he would have died otherwise from “a lack of oxygen in his lungs”. Last year Colorado-native Daniel Granberg, aged 24, died from HAPE in the Bolivian mountains while trekking at 20,391 feet. His only warning signs were a cough and a headache the night before.

So if you find yourself or someone else in the mountains with pneumonia-like symptoms, act fast and seek help as HAPE can progress suddenly to a “stress failure” of the pulmonary capillaries. If you have experienced altitude sickness in the past, you are more at risk for HAPE. Other risk factors include being male, being at low temperatures, sleeping at altitude and conducting intense exercise. A simple way of self-diagnosis is a pulse oximeter which measures your blood oxygenation via a pulse sent through your fingertip. Oxygen levels will typically fall well below 90% with HAPE. If you are worried or have a history of experiencing altitude sickness, do carry a pulse oximeter with you. These devices are small and easy to use and could potentially save a life. And as always: don’t go into the mountains alone or without letting someone know your intended route.