The goal of many backcountry skiers has long been to find better snow and fewer people than what can be found in ski resorts. This goal routinely exposes backcountry travelers to avalanche risks that are hundreds or thousands of times greater than what is found in a ski resort. Twenty years ago, backcountry skiing was a small, dedicated group of enthusiasts who schlepped heavy gear on skinny skis to take advantage of fresh snow that was still bountiful a few days after a storm cycle. Giving the snowpack a few days to consolidate and adjust to the new load often results in less avalanche risk. But, the way backcountry skiers approach their sport is changing. Lighter and wider skis, better boots, and better waterproofing have enabled backcountry skiers to push further and faster into the backcountry, drastically increasing their exposure to risk from avalanches. These gear improvements are fundamentally changing the way people approach backcountry skiing. Now, some avalanche professionals want to bring about a similar change in how the backcountry skiing community approaches avalanche education and training.

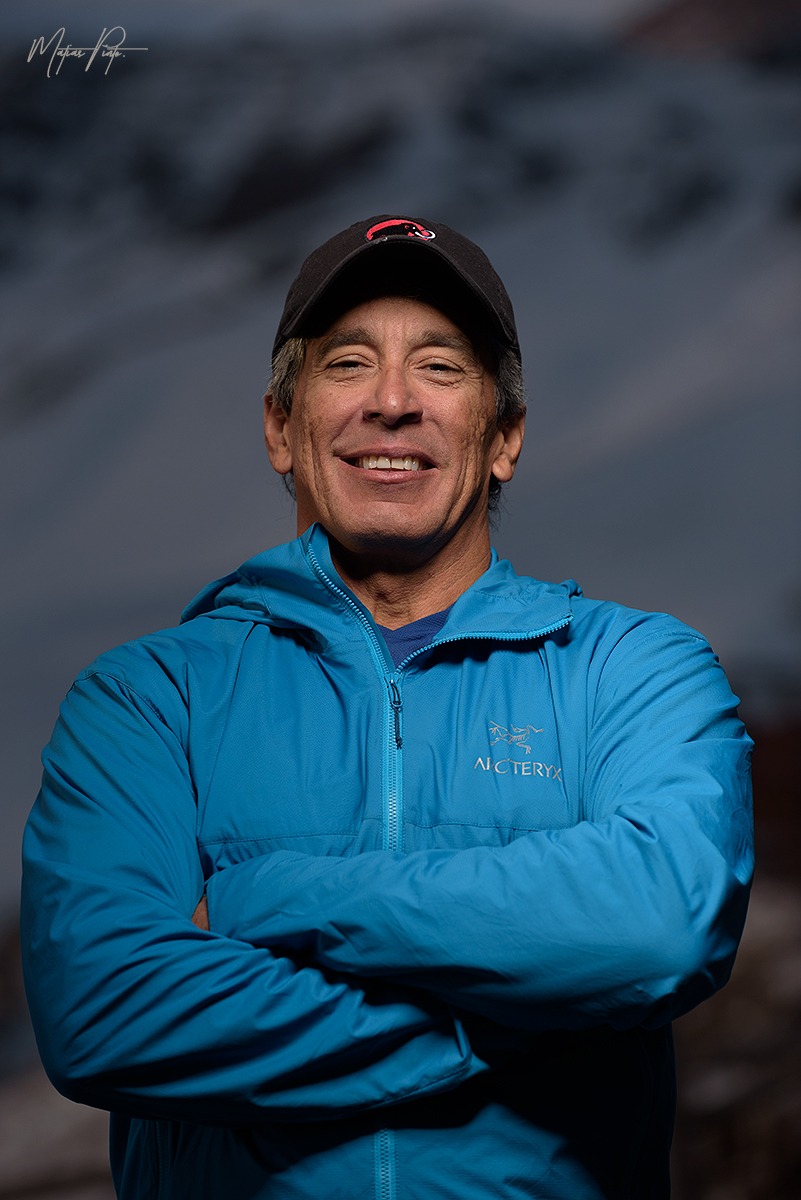

Backcountry skiing used to largely be a spring sport, and people seldom went uphill during a storm, opting to wait a few days for the weather to clear and the snow to settle. Santiago ‘Chago’ Rodriguez, an avalanche educator and ski guide based in Boise, Idaho, has been backcountry skiing long enough to witness and experience this change. Now, he says it is time to change how we approach avalanche education to match the development of backcountry skiing. Chago, the owner of Avalanche Science Guides, has recently departed from the American Avalanche Association model for avalanche education, creating his own progression of avalanche rescue and education courses.

The American Avalanche Association loosely oversees avalanche education in the United States through standardized course guidelines and instructor certifications. While avalanche education originated with the Alta Avalanche School and the National Ski Patrol in the 1950s, these early programs were focused on training professionals from ski areas and the Forest Service. Education focused on recreational backcountry travelers would have to wait until the 90s. The American Institute for Avalanche Research and Education started operating in 1995 with a focus on standardized training for ski guides, and the American Avalanche Association issued its first guidelines for Level 1 and Level 2 courses in 1999. Since then, course guidelines have continued to be reviewed and refined.

In October 2013, the American Avalanche Association began a discussion across the avalanche industry of the need for refinement to avalanche education. Previously, Level 2 Avalanche Safety courses contained a mix of professionals and recreational users, but course content was pitched more toward professionals. The truth is that recreational users have little use for the standardized tools and methods of recording snowpack observations that are paramount to being an avalanche professional. Based on these discussions, the American Avalanche Association launched its new professional-level training program in 2017. All travelers of avalanche terrain still take the same Level 1 course, now termed ‘Recreation Level 1’, but now professionals are funneled towards ‘Professional Level 1’ and ‘Professional Level 2’ courses. At the same time, recreational users are encouraged to take ‘Recreational Level 2.’

Among the backcountry ski community, the paradigm has long been that once you’ve completed a Rec 1 course, you’re good to go backcountry skiing. However, the data regarding Rec 1 courses’ effectiveness at reducing avalanche accidents or fatalities is unclear. As early as 2000, Ian McCammon, an avalanche researcher with the National Outdoor Leadership School, showed evidence that some basic training in avalanche science may lead to certain user groups taking on more risk.

Chago points out that the old, or current, system worked for a long time since the number of backcountry users has been growing steadily, but avalanche deaths remained relatively constant. But now Chago says the way people approach backcountry skiing and the risks are changing. “We want to go to the backcountry and ski the day the snow comes down. We want to ski the day with the highest risk.” Chago is advocating for a change in how we teach the public about avalanches in response to the evolving ways we approach backcountry skiing. Rescue and terrain identification are two significant areas Chago is focused on improving.

“We have a system of education that does not emphasize rescue,” Chago said. The American Avalanche Association guidelines for an avalanche rescue course recommend eight hours of training. Rec 1, the standard for most backcountry travelers, does include rescue in its core curriculum content, but it is the last item. A rescue course is not required for Rec 1, nor does it make the recommended list of prerequisites. Chago approaches things differently.

In October 2023, Chago unveiled a new education progression distinct from that of the American Avalanche Association. Students will start with a two-day rescue course, an industry first. Avalanche Science Guides Level 1, or ASG1, introduces new backcountry users to best travel practices and gives them lots of rescue practice. With a solid foundation in rescue from ASG1, students learn more about terrain identification, snow science, and the like in ASG2 and ASG3. Rescue practice features heavily throughout the ASG progression and is accompanied by a few thousand vertical feet of ski touring.

Mastering a five-minute rescue, the industry-standard, takes a lot of practice but saves lives. Many studies have shown an exponential drop in survivability as the burial time extends beyond ten minutes. A good rule of thumb to remember is that roughly 90% of victims survive a ten-minute burial, but around half do not survive a twenty-minute burial. A successful rescue involves accessing the slide path, conducting a rescue beacon search, efficiently completing a probe search, and digging the victim out, which can often include removing several cubic meters of snow. Any one of those tasks could take up to five minutes if someone is not familiar with their equipment or is out of practice. Chago said that, on average, people are skiing in more dangerous conditions and on more dangerous terrain than what was skied ten or twenty years ago. To account for this added risk, we need to be better at rescue, which means regular practice and striving for the five-minute standard.

One aspect of Chago’s teaching that has set him apart from the beginning is his willingness to bring students into avalanche terrain to teach them about avalanches. Many other avalanche courses are reluctant to bring students into terrain steep enough to host avalanches and only do so when conditions are suitable. Chago argues that students will likely venture into avalanche terrain to ski anyway, so he says if he can take them there first and help them recognize the risks and connect it to the need for a strong foundation in rescue and snow science, then he is doing the ski community a service.

Chago has designed the ASG progression of courses to encourage backcountry skiers to continue their education every winter. Rec 1 courses have long struggled with how to help students drink from the firehose when they receive a huge amount of information about avalanche science and backcountry travel in just four or five days. On top of the firehose effect, very few Rec 1 participants go on to take Rec 2 classes or to refresh their Rec 1 skills, leading to a false sense of security in the backcountry community. Each of Chago’s courses builds on the material from the last course and tries to instill in its participants the need to continue learning after the course is over. In addition, each course involves between 1,000 and 4,000 vertical feet of ski touring, including descents in avalanche terrain, making the ASG classes part avalanche education, part guided ski trip in the relatively untracked Mores Creek Summit area of the Boise Mountains.

According to Chago, the American Avalanche Association has resisted the idea of a two-day rescue course. While their guidelines certainly highlight the need for avalanche rescue training, Chago does not think it is emphasized enough. “We need to create a culture of rescue,” Chago said. The tides are changing, if only slowly. Since 2020, Teton Gravity Research has released ‘Safety Week’ videos every year, many of them showcasing professional skiers practicing avalanche rescue techniques.

The last few years have seen a tremendous rise in outreach and awareness education by local avalanche forecast centers. Many of these efforts are free presentations to the public about where and how avalanches can occur and how to avoid avalanche terrain. Though these programs appear extremely helpful, Chago doesn’t think so. “People want to learn about avalanches. People want to be safe. The Avalanche Centers want to be engaged with the community, but what they are doing is not serving the community,” Chago said. While Chago agrees that the quality of most of this ‘Know Before You Go’ content is fine, he sees it as short-circuiting the desire for more avalanche education and training. Plus, Chago said, there is no focus on rescue.

Chago partly developed his course progression because he saw the American Avalanche Association as relatively inflexible. “The avalanche community is discouraging innovation, experimentation, and creativity,” he said. Part of the issue, according to Chago, is the misplaced expectation that government groups, like Forest Service avalanche centers, and nonprofit groups, like the American Avalanche Association, should not be expected to be as innovative as for-profit companies, like Avalanche Science Guides. Chago acknowledges that all three entities are valuable and have advantages, but he emphasized the relative ease with which Avalanche Science Guides could change their educational approach.

Beyond Idaho, Chago teaches avalanche education courses in Chile, Argentina, Iceland, Spain, and Romania. In each location, Chago seeks steep areas that can develop snow on top of weak layers. These parameters keep the skiing fun and help students learn by giving them something to look at and feel under their skis. He said that the people in these communities have also been underserved by avalanche educators in the past, and people are enthusiastic to learn.

Avalanches will undoubtedly kill people this winter. Many of the victims will have had avalanche training. The stochastic nature of avalanches makes them a risk to anyone who travels in the backcountry, no matter how much training or experience they have. Chago, the American Avalanche Association, forecast centers, and the rest of the avalanche industry all want the public to better understand the risks of traveling in avalanche terrain and to have the best training possible. Through discussion, innovation, and experimentation, avalanche education will continue to improve. For now, consider breaking out your beacon and getting some rescue practice in with your touring partners before the snow stacks up in the backcountry.

More from Zach Armstrong:

- Forest Service Budget Challenges Threaten Avalanche Center Operations Nationwide

- The Battle Over The Future Of Palisades Tahoe

- How the Fatal GS Bowl Avalanche at Palisades Tahoe, CA, Happened and Why it Could Happen Again

- Inside the Ski Industry’s Post-Pandemic Boom

- How Eldora, CO, Ski Patrollers Finally Got Their Union

I believe one of our biggest problems is profit-based avalanche education. This is evident in the fact that companion rescue is separate from Avalanche level 1 in the A3 curriculum. More classes equals more money. A3 who is in reality mostly AIARE guides want to generate more classes. Again evident by the fact that they came up with their pro/rec split. We should be focused on education and not certification. The National Ski Patrol was the first organization teaching avalanche education in the US and in my experience still have the best curriculum. Oh, and by the way it’s by far the cheapest. So support your local NSP Ski Patrol, the original professional provider.

I shiver at the thought of taking anyone into avalanche terrain under the guise of “safety training.” Even with a lifetime of training and experience, it only takes one death to say “well, that wasn’t a good idea.” Not sure if any insurance company would ever take this program on as a client? I commend Mr. Rodriguez fortitude and advanced thinking towards staying alive in the backcountry.

Probably ought to do some fact checking and think about a rewrite here. A variety of factual errors about the history and current state of avalanche education here, would’ve taken a 30 second google search to clean it up.

Always interesting to read others perspectives on education. Zach Armstrong, did you speak to the American Avalanche Association before publishing this article?