In the glossy world of elite winter sports, where athletes race at breakneck speeds, perform adrenaline-fueled jumps, and push themselves to the limit of their abilities on the slopes and tracks around some of the most beautiful ski resorts in the world, a dark reality lurks behind the scenes. Behind the curtain of podiums, medals, and trophies, a silent battle rages on. Eating disorders and other mental health challenges have woven their way into the lives of many elite winter sports athletes, casting a shadow on their achievements and highlighting the high-pressure environment they navigate. An ongoing study by the Eidgenössische Hochschule für Sport in Magglingen in Switzerland found that many elite Swiss athletes suffered from mental health struggles, ranging from depression (17%), anxiety (10%), eating disorders (22%), and sleep disorders (18%). In fact, many studies across the globe have found that the prevalence of eating disorders among athletes is very common and the concerning thing is that they can be fatal. Eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa, anorexia athletica, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder, can have particularly detrimental effects on winter sports athletes due to these athletes’ increased nutritional requirements.

“Mental health is physical health. Eating disorders are not a behavioral choice. It’s mental health, and it’s important that we can talk about mental health,” U.S. cross-country skier Jessie Diggins said.

It may come as a shock that almost a quarter of elite athletes admitted to struggling with eating disorders. However, the pressure elite athletes are under is a contributing factor to the problem. While their bodies might exemplify health and fitness on the outside, the expectation of perfection and associated pressures are leaving these young people predisposed to mental health issues, particularly eating disorders. Perfection is not just a goal but a daily expectation. The demands of their sport, coupled with the relentless pursuit of excellence, often lead to a delicate balance between physical prowess and mental well-being. The pressure to perform at peak levels, maintain a certain physique, and excel under the scrutiny of coaches, trainers, and nutritional advisors as well as the expectations of their peers and a sometimes global audience can take a toll on their mental health. Furthermore, winter sports athletes need to travel extensively for training and competitions, resulting in a loss of their support network of local friends and family, which especially leaves youth athletes vulnerable.

While the problem is not solely a female problem, eating disorders affect female athletes disproportionally to male athletes. There are also variations in frequency by winter sports discipline, with more reported cases in sports where body weight plays a crucial role in performance. Ski jumping, for example, has a widespread problem of underweight male athletes. Several famous ski jumpers, such as Germany’s Sven Hannawald or Czechia’s Vojtech Stursa, shared pictures of their skeletal bodies which have sent shockwaves through the media. Hannawald’s struggles to maintain an unhealthy low body weight of 137 pounds (62 kilograms) at a height of 6 foot 1 inch (1.85 meters) resulted in the introduction of a ratio for ski jumping athletes by the International Ski and Snowboard Federation (FIS). Under this formula, a lower Body Mass Index is compensated by a maximum ski length to discourage athletes from aiming for extremely low body weights.

Nutrition takes center stage for elite athletes as numerical assessments of their physique are a common component in athlete monitoring protocols. The optimization of body composition, including weight and/or body fat loss, is a common goal within an athlete’s nutrition plan. Athletes are assessed regularly for their muscle and fat mass as well as their aerobic and anaerobic fitness. The quest for the perfect body composition and weight can spiral into dangerous territory, impacting not only their physical health but also their mental and emotional stability. The constant focus on body fat and muscle composition and its impact on performance can create a toxic cycle of self-doubt and dissatisfaction. Athletes are subject to regular performance and health checks where weight and strength are assessed throughout the year and not just during the winter months, creating a constant feedback loop. As sport science evolved over the last 20-30 years, strength programs during off-snow periods became the norm for ski athletes. As sports medicine continues to evolve, athletes’ performances are pushed to new heights every year, resulting in ever-higher demands on their bodies.

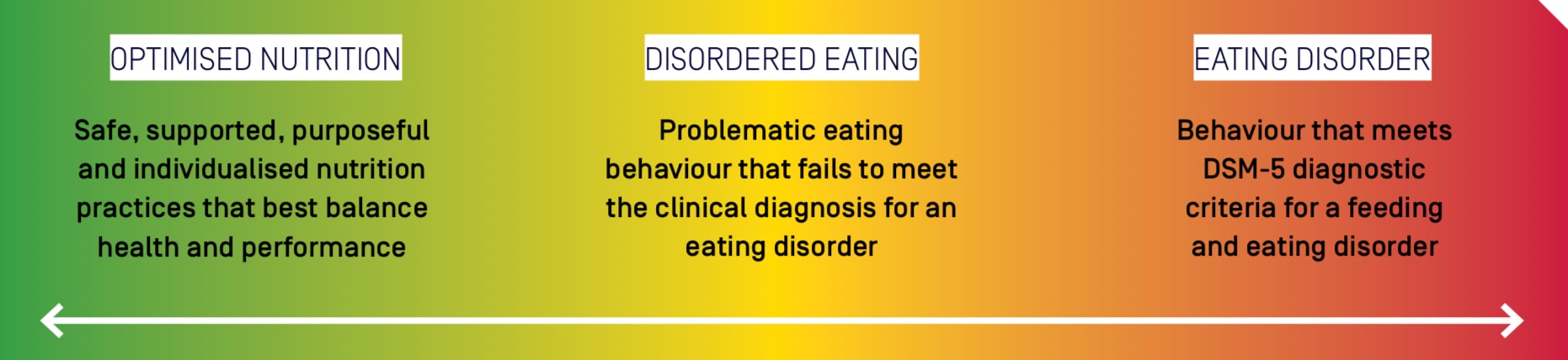

This consistent focus and control can easily become a slippery slope from optimized nutrition to disordered eating to eating disorders. The Australian Institute of Sport and the National Eating Disorder Collaboration define optimized nutrition as the “safe, supported, purposeful, and individualized approach to food and body image.” Eating disorders are characterized, according to the American Psychiatric Association, as problematic eating behaviors, distorted beliefs, preoccupation with food, eating, and body image. They can result in significant distress and impairment to daily functioning. In between the two extremes sits the disordered eating category, where individuals may not be noticeably limited by pathogenic eating but display many of the characteristics, such as occasional purging, the use of diet pills, restrictive eating, or over-exercising to burn calories. The line can blur from disordered eating to eating disorders, and many sufferers will fluctuate between the two categories.

There is a range of eating disorders, the main being: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). To put it simply, in anorexia nervosa people do not eat or eat extremely limited amounts, typically less than 500 calories a day. In bulimia nervosa, those affected will regurgitate the food they ate, often after binge eating, while in ARFID people will eat only a limited range of foods, for example just fruit or just vegetables, which deprives the body of nutrients and results in malnutrition. There are also subforms, such as anorexia athletica, where the focus is on burning more calories through exercise than the intake. What all eating disorders have in common are a distorted body image and an obsessive relationship with food that disrupts normal life, all of which can result in death. Eating disorder fatalities do not necessarily result from starvation but often from heart failure, as these disorders can damage the heart through malnutrition and electrolyte imbalances. This damage can lead to congestive heart failure or sudden cardiac arrest. A vegan influencer who promoted her ARFID as a healthy lifestyle on social media died from her untreated eating disorder in July 2023. She is just one of thousands of eating disorder fatalities. In the U.S. every 52 minutes someone dies from an eating disorder. That’s more than 10,000 people a year. People with anorexia have the second highest mortality among psychiatric conditions.

Eating disorders don’t necessarily stem from the pressure put on athletes by their sports associations but often the internalized self-image that becomes the stumbling stone for many young athletes. Swiss Alpine skier Alessia Bösch has been very open about her struggles with anorexia. “You are very exposed. In a race suit, you see everything. There are media teams and photographers and your pictures end up in newspapers, social media, and magazines. You have no control over what pictures they show of you,” Bösch explained. The Swiss Alpine skier admits that she would look at pictures and hate how she looked, “I would think, ‘You do so much sport, you work out three to four hours a day, you should be thinner, you should have more muscle definition, you should look sportier.’ That was a real challenge for me.”

Bösch explained that she initially got sucked into the vicious cycle of eating disorders through the feeling of control that restricted eating provided. The disease struck her when she had immense pressure building on the young teenage athlete. Bösch won four U-18 national youth championship titles in Alpine skiing and made the Swiss National Alpine Team as a teenager. She is the sister of Slopestyle and Big Air skier Fabian Bösch. She told me that when the stress of high school finals was at its peak, their father was unexpectedly diagnosed with incurable brain cancer. “My eating disorder became my coping mechanism. I felt like I was losing control of my life but I had this area in my life that I could control, where I can compensate,” Bösch admitted.

The control aspect is a common thread for many of these high-achieving athletes. When everything in your life is out of control, what you put in your mouth invariably becomes the only thing you can control. U.S. cross-country skier Jessie Diggins concurred with this sentiment in a press conference, “People should understand: often it is not at all about food or your body. It’s about looking for a feeling of control when you feel like you have none in your life. It’s about looking for an illusion of feeling safe when you feel like things are spiraling out of your control. So for me, I had been working too hard for too long and I was feeling incredibly overwhelmed and my eating disorder served as a crutch to kind of numb these overwhelming feelings when I felt like I couldn’t deal with them.”

What puts winter sports athletes’ health particularly at risk is that they compete and train at altitude and colder temperatures, thus increasing their need for calories. Colder temperatures require a higher calorific expenditure to maintain the core body temperature on top of the anaerobic and aerobic load of training. This can exacerbate the effects of malnutrition in athletes. Youth athletes, who are growing, show a much higher energy expenditure according to a study by Ekelund et al from 2002. Disordered eating and eating disorders in winter sports athletes lead to lower energy availability which in turn can increase the risk of illness and injury.

These youth athletes are also the most vulnerable when it comes to societal pressures to conform to beauty standards set by social media and society as a whole. Furthermore, maintaining a social media profile is important for attracting sponsors, and especially for female athletes this can mean conforming to body ideals that may be below their optimum weight, as women are particularly subject to more public scrutiny on their weight than male athletes. “You have double the pressure,” Bösch explained. “You have the normal societal pressure as a girl of how you are supposed to look like to be considered pretty or attractive. And social media has made this so much harder. You are confronted 24/7 as a young woman these days with images of seemingly perfect women. And then as an athlete, you are told what to eat and what body fat you should have. If you are insecure and critical of yourself, it’s an easy trigger when a coach tells you that you should eat or not eat certain things. At some stage, I forgot what intuitive eating was. I forgot what it was like to eat like a normal person. What is normal eating? I totally lost the whole concept of what was normal. Food was not a source of energy. Food was a source of disgust.”

The hardest part is realizing that there is a problem because these highly competitive athletes tend to cover up their struggles to others and are often in denial until their health becomes compromised. Realizing that they are not in control but have spun out of control is very hard for most sufferers and denial to themselves and lying to others becomes chronic. “For the longest time, I thought, everything is okay, everything is under control,” Bösch explained. “After two, three months I started to lie more and more about eating. Preparing the lies became such a burden. I started to wonder, why am I lying to my friends? I like cake. Why am I saying I don’t want any? I was in denial and I ended up being taken to a clinic and for me, that was the key point that I needed to fix this. I did not want to end up in there. I did not want to be that person.”

Bösch announced her retirement from competitive skiing in December 2021 and, with the help of a psychologist, focused on her health. “I did not go to the clinic. I asked them to give me a month and I had a psychologist who helped me,” she explained. Bösch wanted to get better and initially used the psychologist and later a backpacking trip to Asia to recover from her struggles with anorexia. “Nobody there cared about all the things that ruled my life. It was so liberating! People worried about where to catch the next wave, where to surf tomorrow—that was it,” she said.

Similar to Bösch, Diggins was dealing with the stress of high school on top of her athletic career when she first realized she had a problem with eating disorders. Diggins utilized the help of the Emily Program in Minnesota. “When I was 18, I did not know much at all about mental health or eating disorders and I thought it was just my fault,” she said. “I thought I was a bad kid. I thought it was a behavioral problem or a choice that I was continuing to make wrongly over and over again.” The Emily Program helped Diggins understand how her brain worked and that her struggles were in fact a mental health problem.

Diggins has been advocating for a better understanding of mental health and for breaking down the stigma associated with eating disorders for many years. Diggins encourages people to share their stories and to seek professional help, explaining it by saying, “If you fall and break your arm you don’t just go ‘Oh if I try, I can fix this myself’. You go to a professional or a hospital!” Diggins believes that by sharing her struggles, she can help others. “I have had a lot of people advise me, maybe you shouldn’t [share this]. It makes you really vulnerable. And healing your mental health in private is also totally okay.”

Despite the stigma and shame often associated with mental health struggles, these two winter sports athletes have bravely spoken out about their experiences. Their stories shed light on the pervasive nature of these issues and the need for greater support and understanding within the winter sports community. Initiatives aimed at promoting mental wellness, providing access to counseling and support services, and fostering a culture of openness and acceptance are crucial steps forward. “When I went public with my anorexia on social media I had so many international responses,” Bösch shared. “Eating disorders are a taboo topic. It is an intimate and personal disease, and no one talks about it, and it makes it doubly hard. I was made to feel like I needed to be ashamed. I wondered why I could not be normal. I think if I had known someone who had suffered from it, someone I could have turned to, that would have helped me feel less isolated. Once I went public, so many other athletes—skiing and other sports—told me that they were so grateful I had shared my struggles.”

Open and honest conversations around mental health issues will help more athletes step forward and admit they need help without the fear of being eliminated from national teams or demoted to a lower team. It will also enable them to get the right help when they need it and help create a safety net should an athlete relapse. Diggins admits she spent 12 years building a support network in case she needed it. When she suffered a relapse before the 23/24 season, she had a safety net to catch her. “All my coaches were amazing, “ Diggins confirmed. “The way they responded, it wasn’t like ‘Oh, I can’t believe you are doing this again’, it was like ‘Wow, I’m really sorry to hear you’re in this place. I am here for you and how can I help? I am ready to be here for you. What can I do’? And that gives me a lot of hope that if I get this response from all of my support people, other athletes can get this response too if they need it when they need it.”

Addressing eating disorders and mental health challenges among elite winter sports athletes requires a multifaceted approach. Coaches, trainers, sports organizations, and healthcare professionals must work together to create a supportive environment that prioritizes not just physical but also mental well-being to prevent eating disorders. Mental health support for athletes is especially vital as they will typically be geographically removed from their usual support network. In addition, education about healthy nutrition, body image, and coping mechanisms for stress and pressure should be integrated into training programs early. A positive body image is one of the key protective factors against developing eating disorders.

Recovery from eating disorders and mental health issues is a journey fraught with challenges but also marked by resilience and hope. Athletes who seek help and embrace a holistic approach to their well-being can reclaim their strength, both on and off the slopes. By destigmatizing conversations about mental health and fostering a culture of compassion and support, the winter sports community can empower athletes to thrive, not just survive, in their pursuit of excellence. Jessie Diggins went into the 2023/2024 season with renewed strength, posting the most successful season ever for an American cross-country skier. Diggins was awarded the Holmenkollen Medal and claimed both the Overall FIS Cross-Country title as well as the Distance title. Meanwhile, Alessia Bösch is working on her comeback to competitive skiing. “I needed the time and distance to realize how much I love this sport,” she admitted. “I know the way is long and hard but I know I have to give it a go.” She is training as an independent athlete and hopes to make it back on the Swiss National Team. Diggins and Bösch’s stories serve as a poignant reminder of the price of perfection in a high-stakes environment. By shining a spotlight on these issues and advocating for meaningful change, we can create a future where athletes are celebrated not only for their athletic prowess but also for their resilience and well-being.