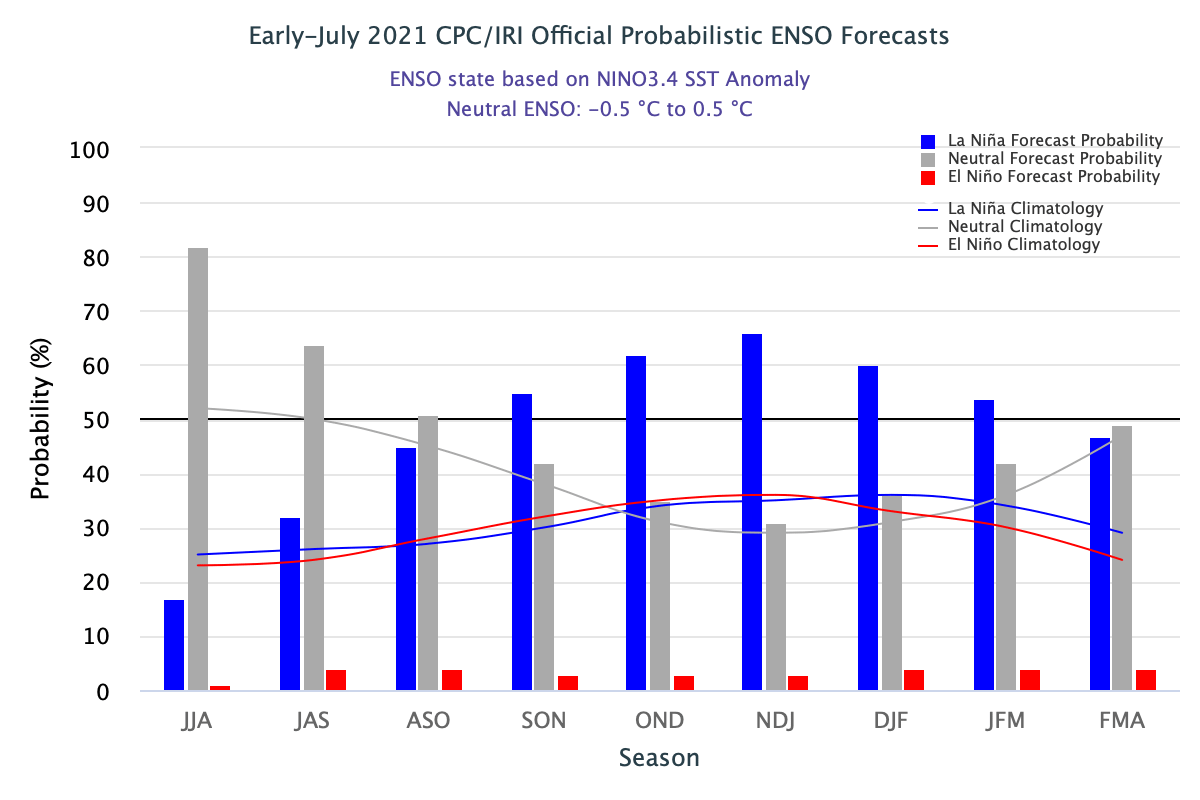

As things stand with the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), neutral conditions are currently present in the tropical Pacific and favored to last through the North American summer and into the fall. But forecasters at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center have issued a La Niña Watch, which means they see La Niña likely emerging (~55%) during the September-November period and lasting through winter.

Where we are:

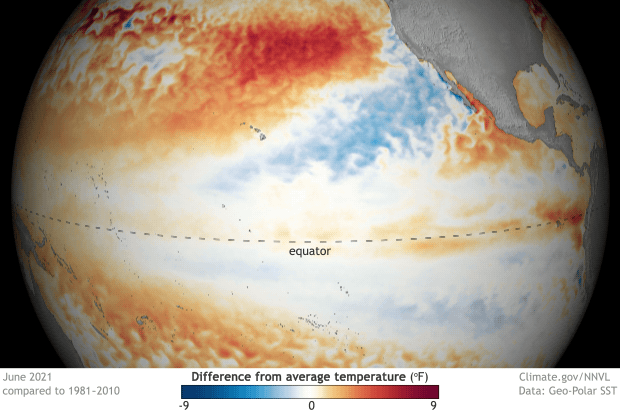

I know you’re all excited for me to talk about La Niña, but I’m a killjoy, so bear with me for a second while I talk about the current state of the Pacific. In June, ocean surface temperatures were near the 1991-2020 average across the equatorial Pacific, including the all-important Nino3.4 region (check out this post for more on ENSO indices), which we use to monitor the state of ENSO. Specifically, the June sea surface temperature in the Nino3.4 region was 0.25 degrees Celsius below average, well within the ENSO-neutral range. Ocean temperatures in this region have been quickly returning to near-average conditions over the last several months, increasing by nearly half a degree Celsius since April and over a degree Celsius since last winter’s La Niña peak.

But as we have said, so many, many times: there is more to ENSO than just the surface of the ocean. Putting on our snorkels, let’s dive beneath the surface of the Pacific, where things aren’t as near average but still firmly indicative of an ENSO stuck in neutral. Waters were slightly warmer than average, except for the eastern Pacific where cooler-than-average waters developed near the thermocline—the layer of water that marks the transition between the warmer upper ocean and colder deeper ocean. But overall, nothing to write home about.

To finish off this trilogy of signs about our current ENSO-neutral Pacific, we look to the skies! After all, ENSO is a coupled atmosphere/ocean climate phenomenon. And for the past month, that atmosphere has been pretty darn neutral. Winds at both low and high levels of the atmosphere were pretty normal, and while thunderstorm activity was reduced near the dateline, things were mostly average elsewhere.

There hasn’t been a more boring trilogy since Star Wars episodes 1-3 (yeah…I said it). But then again, that’s expected during neutral ENSO conditions across the Pacific.

Where we’re going:

It might seem odd, then, with things seeming so… blah… that a La Niña Watch has been issued. To clarify, a La Niña Watch means conditions are favorable for the development of La Niña within the next six months. So, what’s in the climate model “tea leaves” that has helped scientists feel comfortable enough to start throwing the La Niña label around?

The answer, in part, lies in a strong computer model consensus. While most of the models we look at predict ENSO-neutral to continue to last through fall, many models from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) favor a transition to La Niña during the fall and into winter. The NMME is incredibly helpful to forecasters in predicting the future state of ENSO, especially when we are past the notorious spring barrier, a time when model accuracy wanes.

Where’s the beef?

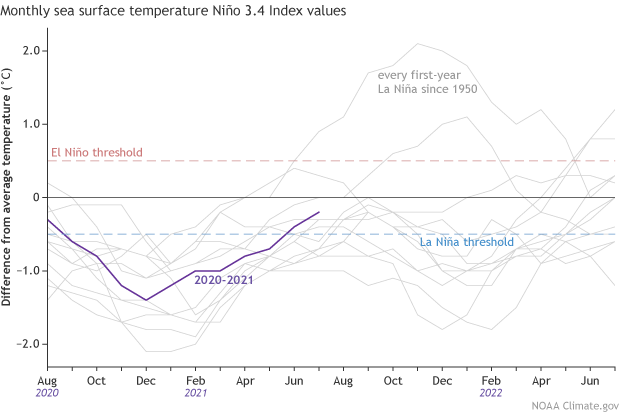

Is it all that unusual to have two La Niña winters back-to-back? Nope! In fact, of the twelve first-year La Niña events, eight (!) were followed by La Niña the next winter, two by neutral, and two by El Niño. Honestly, with those numbers, it would have been more surprising if we thought neutral conditions would continue all year.

Putting all of those 12 first-year La Niñas together with 2020-2021, it’s evident how much this last year doesn’t stand out. Though, twelve past cases are not a ton to rely on by itself. This La Niña Watch is buoyed by much more than that.

One specific reason why and when any change to ENSO is important is the potential influence on the Atlantic and eastern Pacific hurricane season. As noted on the ENSO Blog in the past, La Niña can help make atmospheric conditions more conducive for tropical cyclones to form the Atlantic, and less conducive in the Eastern Pacific. If 2021 so far is any indicator, it could be an active year: through the beginning of July, five named storms in the Atlantic have already formed, a new record-breaking the previous record set just last year. In August, the Climate Prediction Center will issue an updated hurricane outlook, so stay tuned for more info on that. In the meantime, you can read the outlook from May to see what scientists were thinking two months ago.

This post first appeared on the climate.gov ENSO Blog and was written by Tom Di Liberto.

45% chance I can’t do anything about it. 55% chance I can convince my wife to ski the Northwest in 2022.

69% chance the weather changes

ARG!!!