High-altitude pulmonary edema, otherwise known as HAPE, is a form of altitude sickness where a lack of oxygen causes a build-up of fluid in the lungs that, according to the National Institute of Health, can turn deadly in approximately 50 percent of patients if left untreated. As summer recreation booms, SAR teams everywhere are reminding tourists that acute mountain sickness (AMS), sudden and severe high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE), and less common but more serious HAPE are all preventable emergencies. The ability to recognize and treat symptoms in your climbing partner in the field makes all the difference in fast response and recovery.

The pathophysiology of altitude sickness is influenced by many different factors, some revolving around an individual’s genes and fitness, but many risk factors are closely related to how you’re going uphill. Ascending too quickly overwhelms the body’s ability to acclimate to changing oxygen levels and air pressure, but the severity of illness also increases from prolonged exposure at high elevations, and the intensity of exerting energy without adequate rest or hydration.

Classically, HAPE develops 2-4 days into ascent in individuals over 8,000 ft (or 2,500 meters) above sea level but can develop even down to 4,900 ft (1,500 meters) in elevation, so symptoms deserve quick action whenever observed. Acclimatization is the key to preventing a HAPE scenario on your next ski trip. Logistics include planning for campsite elevation lower than the day’s peak gain and building intentional rest days and slow ascents into itineraries. Some mountaineers and scientists out there swear by certain pre-trip medications still being clinically researched.

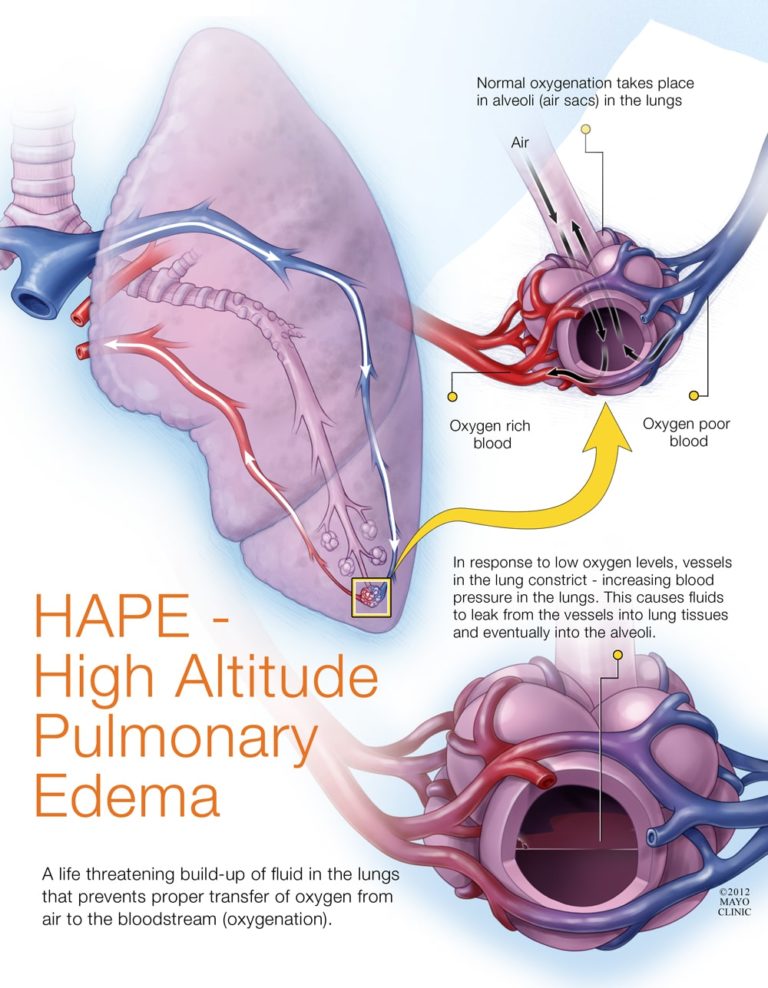

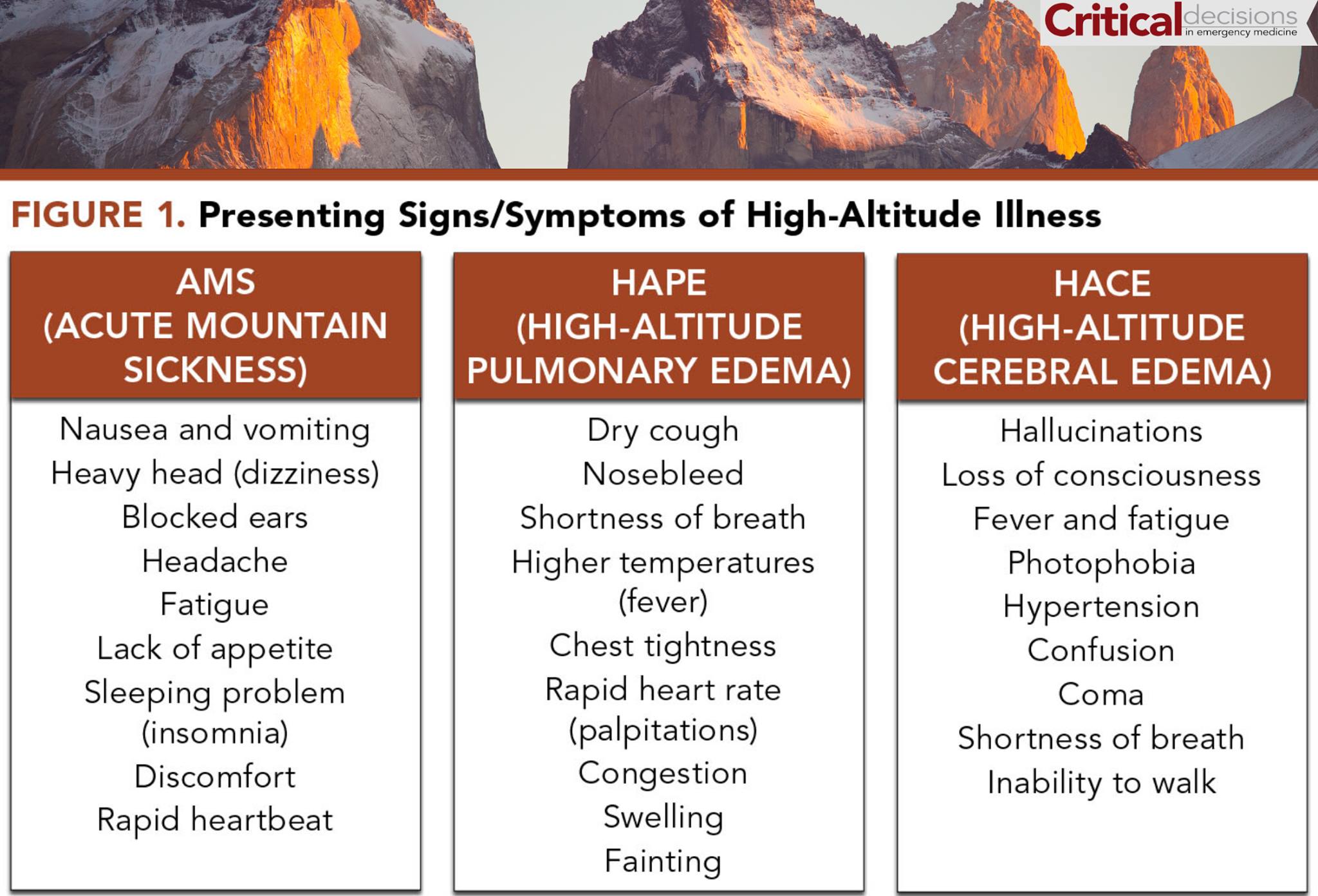

As HAPE is developing, increased pressure in arteries and capillaries in the lungs continues to build until they reach a “stress failure” and fluid starts to pool in the alveoli and leak into the lungs. Relating that to your adventure buddy exhibiting signs and symptoms in the field, you will first notice the presence of signs and symptoms consistent with acute mountain sickness. These symptoms can occur anytime after climbing, including nausea/vomiting, fatigue, loss of appetite, or difficulty sleeping. The body can heal these issues fairly easily when given time to adapt at a lower elevation than preceded symptoms.

If symptoms persist or get worse and start to include confusion or loss of balance, then that individual is moving into HACE territory. Pulmonary edema may or may not be preceded by cerebral edema, but if a patient has progressed to symptoms including a wet, gurgled cough, shortness of breath, or diminishing ability to exert themself then they are in immediate need of retreating to lower elevation and higher medical care. Application of oxygen can also help, and base camps with frequent adverse weather are likely to have hypobaric pressure wraps on hand to stabilize a patient that may need to wait for the weather to clear before they can go downhill. The best alpine adventures are the ones that bring everyone home safely at the end, so keeping an eye out for these symptoms can be an important part of looking out for each other in the high country.