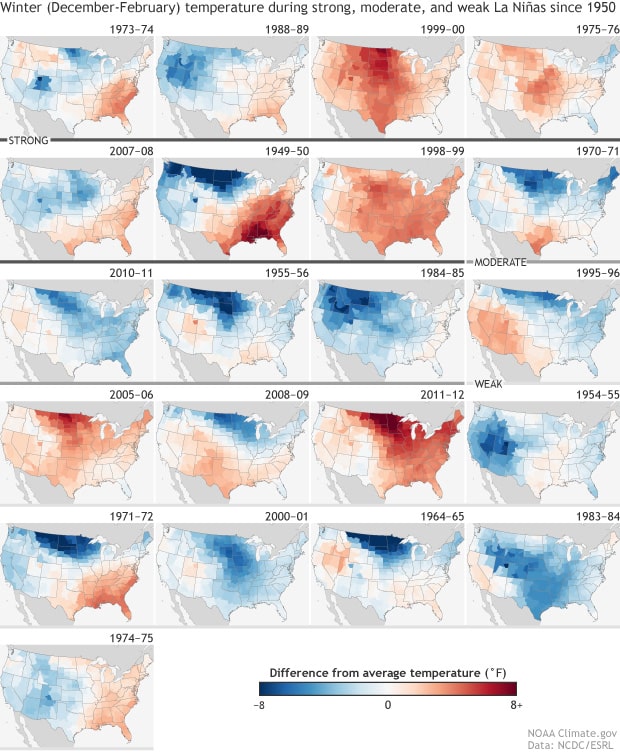

What do July, the ENSO, and Winter 21/22 all have in common? La Niña, of course! NOAA has just released their prediction for a La Niña winter 20/21. As of July, there is a 55% chance of a La Niña winter, which is great news for the Pacific Northwest and the northern Rockies and not-so-great news for the intermountain region and the Southwest.

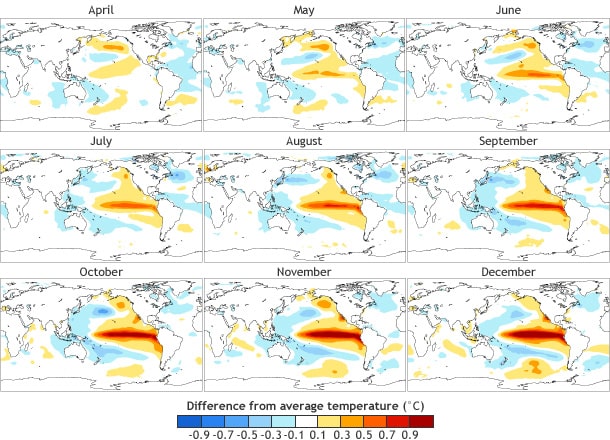

Why July? July is the earliest month in the year that provides data that allows scientists to make good predictions about the El Niño/La Niña status of the coming winter. A good prediction, in this case, means that the data can predict if winter will be El Niño or not about three-quarters of the time.

July is also comfortably past the Spring Predictability Barrier. The Spring Predictability Barrier occurs roughly from February to May. During the Spring Predictability Barrier, even the best or most skilled models cannot make accurate predictions about the coming winter. There are no definitive answers about why the Predictability Barrier exists. Still, many scientists theorize that models are less accurate during this time because the previous winter’s El Niño/La Niña event is decaying, and the next winter’s event has yet to begin.

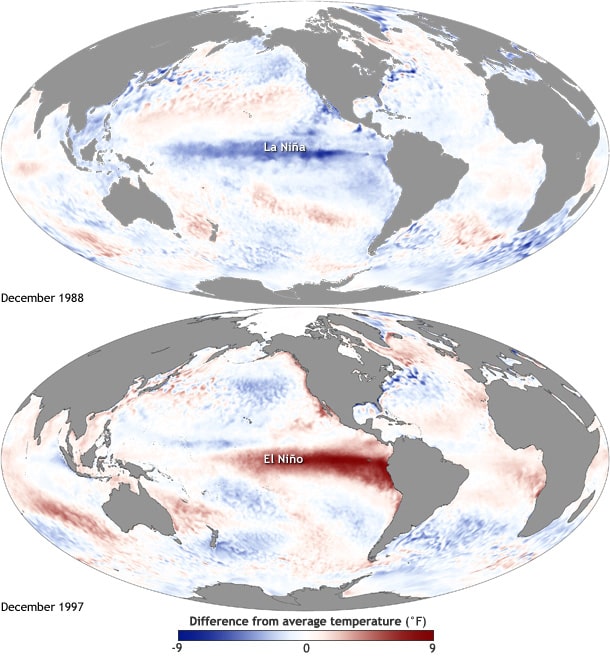

What is ENSO? ENSO stands for El Niño Southern Oscillation, or the changes that cause an El Niño, neutral, or La Niña winter. Basically, if the surface of the eastern Pacific Ocean is warm, it will likely be an El Niño winter. If the eastern Pacific is cold, the winter will likely be La Niña.

The southern oscillation has two components: the atmosphere and the ocean. For scientists to declare an El Niño or La Niña event, the atmosphere and the ocean must show the appropriate characteristics.

The atmospheric component includes the easterly trade winds, which flow from east to west. The trade winds move the warm surface of the ocean away from the eastern Pacific. The movement of the trade winds also causes the western edge of the Pacific to be about 24 inches higher than its eastern side! This causes ocean upwelling, meaning that cold water from the depths of the ocean is pulled up to the surface. Cold water at the surface of the Pacific is necessary for a La Niña event.

The ocean component of the southern oscillation involves something called oceanic Kelvin waves, which one scientist has dubbed “the next polar vortex.” When picturing ocean waves, most people picture surf waves crashing on a beach. Oceanic Kelvin waves are planetary waves, and as such, they occur on an immense scale. They are so huge they can take up much of the Pacific ocean. Because of the Coriolis effect, equatorial Kelvin waves only move eastward and often take 2-3 months to reach the western coastline of the Americas.

Luckily, Kelvin waves are unlike surf waves. While they do have peaks and valleys which cause observable changes to the sea surface height, they do not build and break. Kelvin waves merely slosh from west to east on an immense, planetary scale. Kelvin waves move from the downwelling phase to the upwelling phase, contributing to causing shifts in the ENSO.

The trade winds push the Pacific’s warm surface from east to west. When the east-to-west trade winds slacken, Kelvin waves enter the downwelling phase. The ocean’s warm surface begins to slosh back to the east, and this warm layer pushes down on the deeper, colder water, causing surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific to rise. This will likely create an El Niño event.

Conversely, once the downwelling portion of a Kelvin wave passes, there can be a rebound in the form of an upwelling phase. In an upwelling phase, cold water from the depths of the Pacific rises or upwells. This leads to colder ocean surface temperatures which can contribute to causing a La Niña.

It is important to note that upwelling and downwelling are not equal and opposite. There is no guarantee that a strong upwelling will follow a strong downwelling phase. This is because there is no force in the ocean generating these waves; rather, they are entirely caused by wind acting on the ocean.

While most scientists agree that ENSO is caused by a complex interaction between the ocean and atmosphere, one anonymous employee of a major climate research institute thinks otherwise.

I think the reason for El Niño is the large difference in salinity near the glaciers. I have a strange feeling that the sea beavers are playing havoc with us. There might be high sand dunes at the ocean bed and these might be affecting the ocean flow and hence the difference in temperatures. As most people think El Niño is not due to the weakening of the trade winds.

Whether they are caused by sea beavers or by the results of the complex interplay between ocean and atmosphere, La Niña winters can be epic, and as of July, scientists are calling for a La Niña. Hopefully, it’s a deep one.