I took my role as Editor with SnowBrains four years ago, when I was a young college kid at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. I wanted to ski every day and find a way to make a living from writing, and by some cosmic chance I landed an internship with SnowBrains. Not long after that, I was promoted to an editorial position where I quickly learned the ins and outs of this organization, a skiing and snowboarding media company that provides positive, original, and intelligent ski industry news and snow resources. I learned how to share media covering a vast array of topics from resort news to backcountry trip reports to avalanche incidents and weather forecasts and a whole lot more. I got to interact with a large online presence: 9 million annual users on our website and 15 million annual page views. Social media became a daily tool I used because a lot of our traffic comes from platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. SnowBrains depends on them, and this company’s vision is to one day become “The New York Times” of the Snowsports World.

Our CEO and Founder Miles Clark who hired me said that this vision, combined with a focus on professionalism, could benefit and inspire the ski industry at large in positive ways. I liked the sound of that. As I settled into my role I got to know Miles well and I learned about his background: AIARE Level III avalanche safety, mountain guide, heli ski guide, and pro skier who spends countless days in the backcountry every season. I myself tour most days of the winter, which is perfect because SnowBrains has a large focus on backcountry skiing. We constantly share things like news of avalanche incidents, informative trip reports from our backcountry excursions, and educational resources for avalanche safety. But as time went on, I came to observe some strange things about social media content, specifically about the backcountry. The content, which I shared daily, appeared a certain way when you saw it on social media but in reality, it was actually quite different than the way it was portrayed on a smartphone or computer screen.

The reality of backcountry Instagram content is like an iceberg. You see something enticing right away that looks beautiful and cool and attention-grabbing on the surface, but there’s a lot lurking below. Like everything else that goes into a day of backcountry skiing including the not-so-good or noteworthy stuff. Everything that no one wants to admit or talk about, or the stuff that doesn’t necessarily generate likes or shares, is there but it is not visible. This includes but is not limited to all the decisions and thought processes that went into navigating the avalanche hazard to get up there in the first place; all the intense physical suffering and battling of the elements; all of the mistakes, and red flags, and detours, and bathroom breaks in the cold; all of the fumbling with camera equipment or drones or any other distraction that can be inherent in generating content from the backcountry. All of this “not-so-glorious” stuff is ever present when you go ski touring; but it is not when you are posting on Instagram.

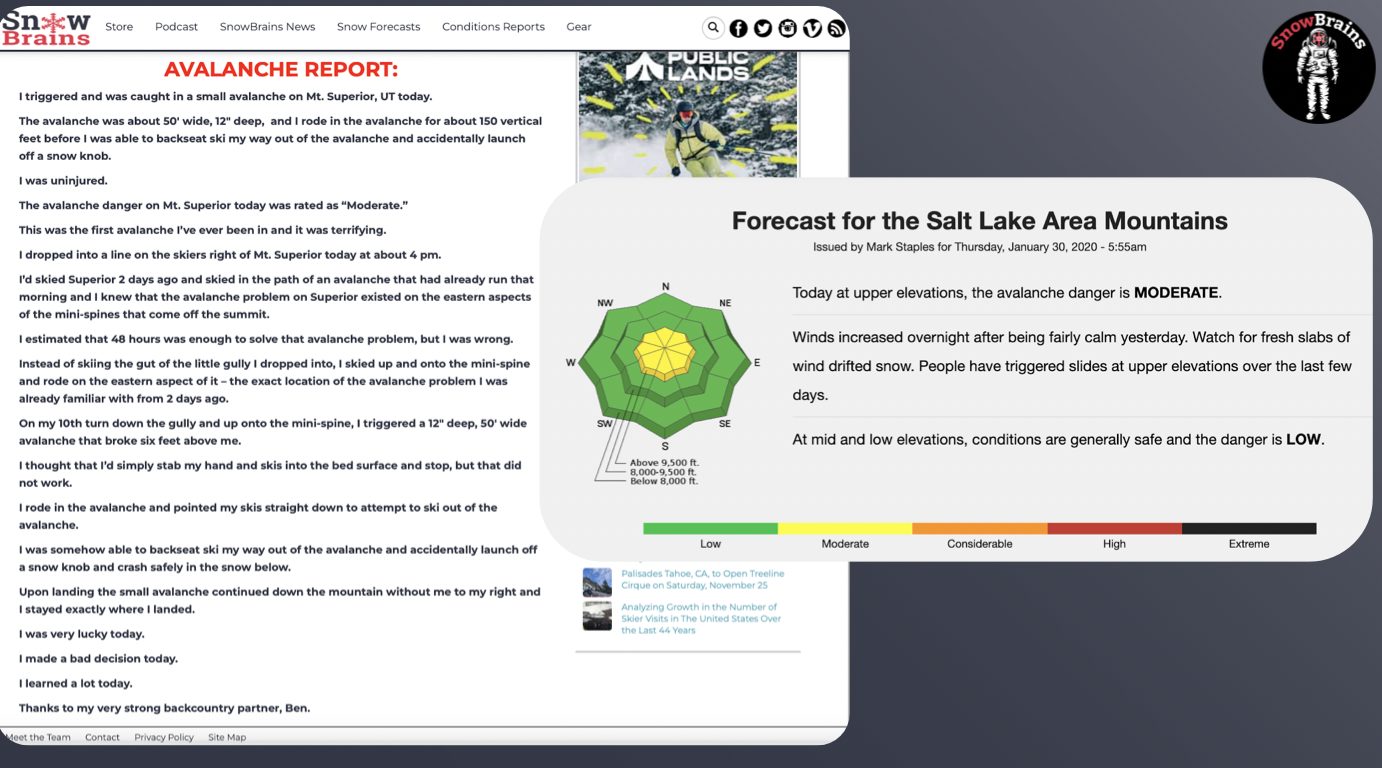

Here’s a direct example: in the first panel of the attached Instagram post above from SnowBrains, you can see the skier getting rad face shots down a backcountry couloir in glorious blower pow. It looks like quite fun, and like a fairly carefree time, right? Like really anybody could do it. Well, that’s the deceptive part. In the second panel is what you don’t often see: a heinous down climb down rock and ice that the skier had to do to get out of the chute safely. You also don’t see the several scratches or core shots on his ski from hitting rocks. Although he might mention it in the post’s caption, you don’t actually see the avalanche danger through your screen. You don’t see the fact that the skier in the video is a professional skier who has competed in professional skiing competitions and that this ability to go up and down a steep, avalanche-prone chute like this one is the culmination of a lifetime’s experience of steep skiing and hard physical training and vigorous avalanche educating. You don’t see all the hours that he’s spent in the freezing cold of a snowpit being graded on his avalanche skills by instructors. You don’t see the pain that his right knee feels from decades’ worth of impacts from skiing and booting up technical lines and dangerous mountains. You don’t see all the people that he’s thinking about that he’s lost because of avalanches as he’s climbing up. People rarely talk about this sort of stuff and they even more rarely show these things on Instagram. But they are always there—no matter how glorious the shot.