This ENSO update first appeared on the climate.gov ENSO Blog and was written by Emily Becker.

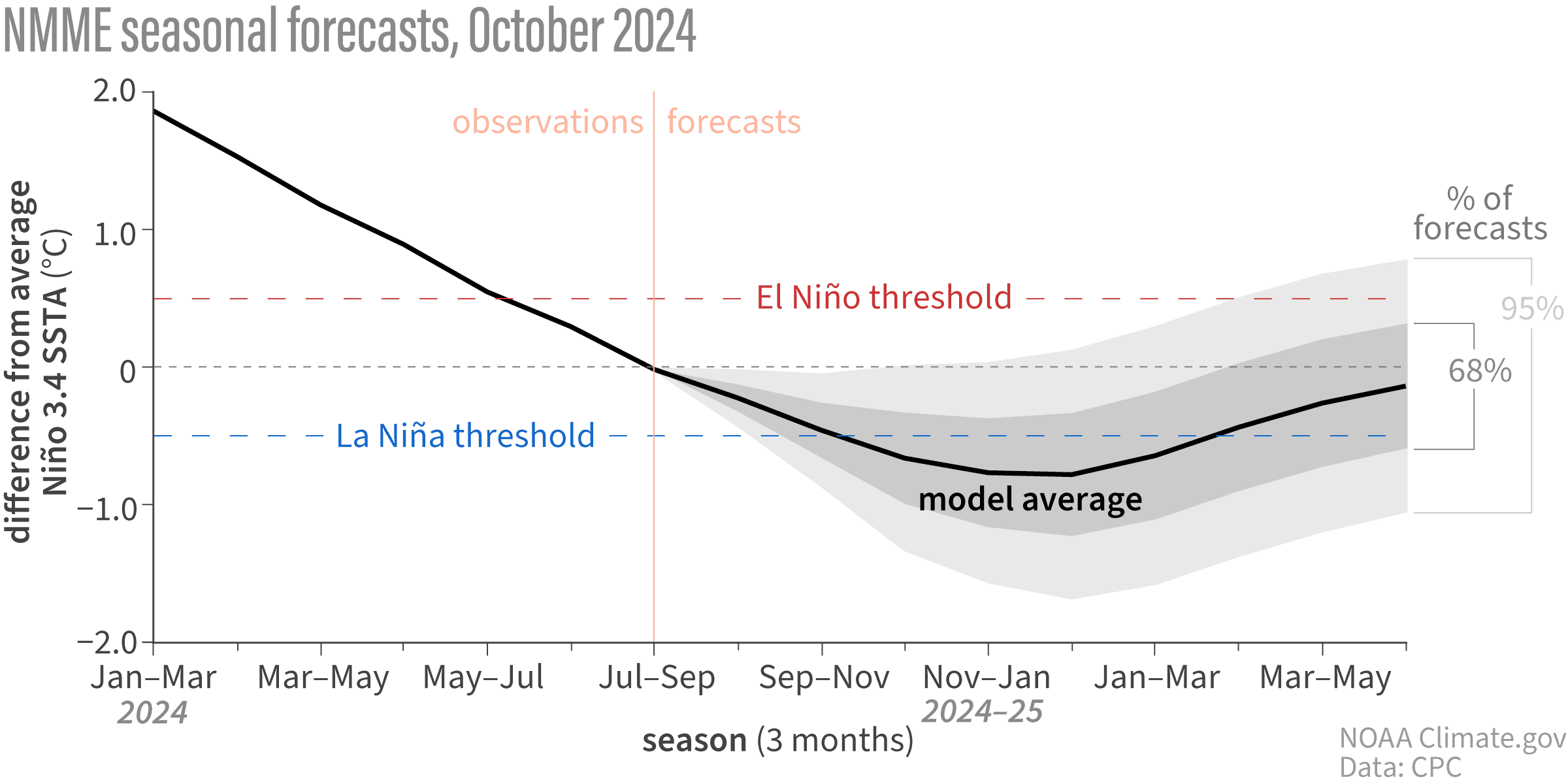

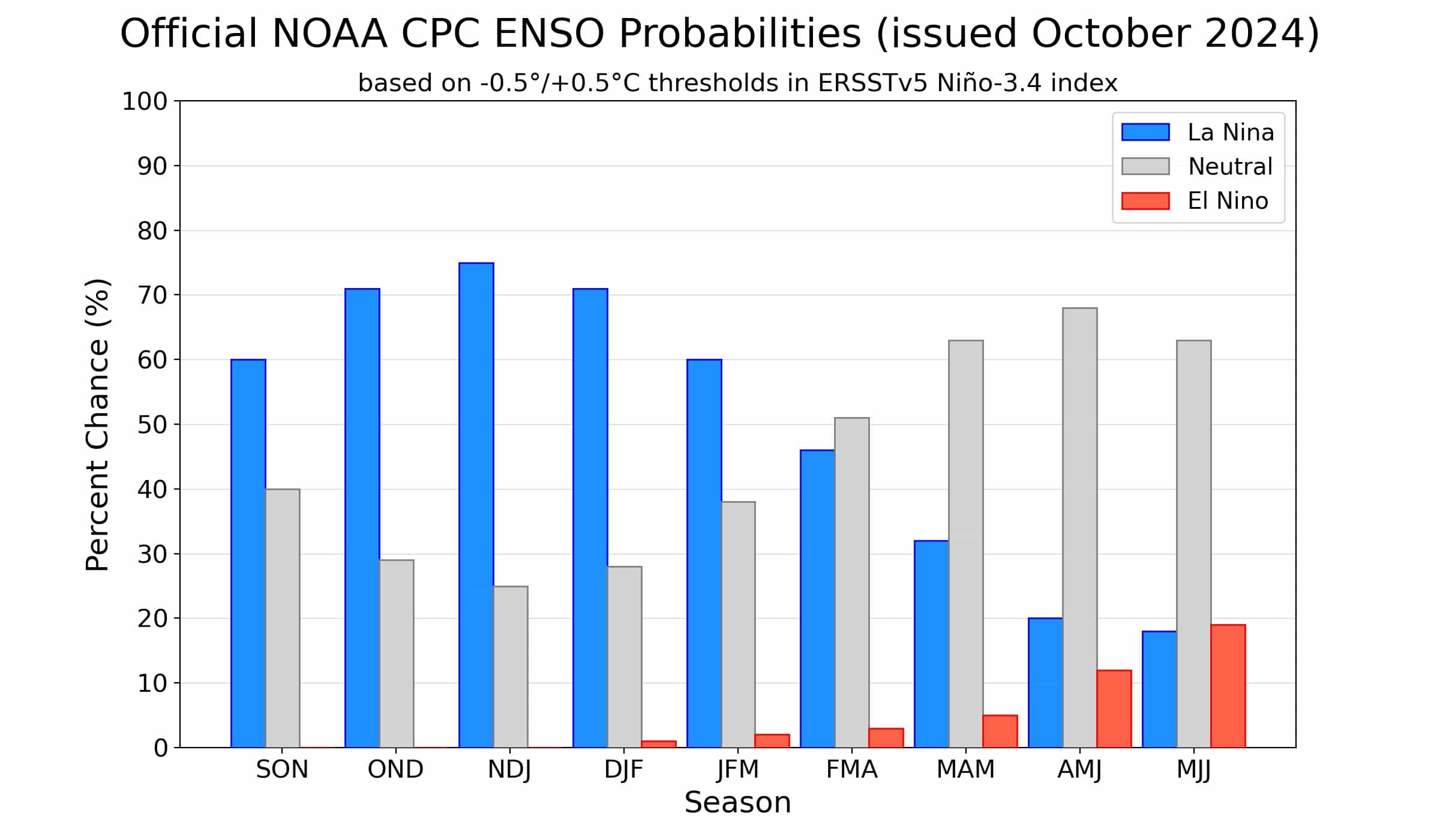

The tropical Pacific Ocean reflected neutral conditions—neither El Niño nor La Niña—in September. Forecasters continue to favor La Niña later this year, with an approximately 60% chance it will develop in September–November. The probability of La Niña is a bit lower than last month, though, and it’s likely to be a weak event.

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore

La Niña is the cool phase of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a pattern of alternating warmer (El Niño) and cooler surface waters in the tropical Pacific. Rising warm air in the tropics is what drives global atmospheric circulation, and therefore the jet stream, storm tracks, and resulting temperature and rain patterns. ENSO’s varying sea surface temperature changes where the strongest rising air motion occurs, hence changing global atmospheric circulation. ENSO is predictable several months in advance, and when you couple that predictability with our knowledge of how it changes global patterns, you get an early picture of potential upcoming weather and climate patterns.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling

Let’s take a spin through recent conditions in the tropical Pacific. The threshold for La Niña is a sea surface temperature in the Niño-3.4 region in the central equatorial Pacific that is equal to or more than 0.5 °C below the long-term average. (Currently, long-term is 1991–2020.) The most recent weekly measurement of the temperature difference from average in the Niño-3.4 region was -0.3 °C, and the September average was also -0.3 °C.

Hurricane Helene’s devastating impacts on the Asheville, NC, region affected NOAA’s data center—see the footnote for details on our new data sources this month. Michelle and CPC’s Caihong Wen did extensive testing and determined that the temporary replacements have historically been very close to the ones we usually use, so we’re confident that ENSO-neutral conditions are still in place.

There has been a region of cooler-than-average water in the central-eastern tropical Pacific in recent weeks, as you can see above, but it’s not quite crossing the threshold. Some aspects of the tropical atmosphere are still reflecting neutral, too. There was a region of stronger-than-average trade winds in the east-central tropical Pacific and a little bit of reduced rainfall over the central Pacific, but overall, no strong, distinct pattern of stronger-than-average trade winds or increased rainfall over Indonesia as we’d expect during an established La Niña. In fact, a couple weeks of average to weaker-than-average trade winds during September allowed the surface to warm a bit.

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

If it seems like we’ve been stuck here in neutral for longer than we expected—we have! Last winter, models were predicting that La Niña would develop rapidly after the end of El Niño 2023–24. So what happened? Why are we still waiting? Didn’t I just say ENSO is predictable?

ENSO is predictable, but only in the big picture, meaning seasonal averages or longer. The signals that tell us that El Niño or La Niña are on the way, such as a large amount of cooler or warmer water under the ocean surface, or a particularly strong, long-lasting shift in the trade winds, are reliable indicators. Also, our computer climate models, which look at current conditions and make predictions based on mathematical and physical equations, are pretty good, especially after the spring barrier (a time of year when predictions are especially difficult).

However, small, short-term fluctuations, such as the weaker equatorial trade winds that occurred during September, can’t be predicted more than a couple of weeks (at best) in advance. They tend to have a disproportionate impact during borderline, more marginal situations when we are hovering near our ENSO thresholds. These small fluctuations can tip the scales one way or the other. In this case, they’ve added up to a slower and weaker La Niña development. That said, many of our models are holding steady for La Niña to develop shortly.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary

Forecasters have nudged the overall chance that La Niña will develop down a bit from last month, though. That means that, while La Niña is still favored, we’re less confident in La Niña emerging.

Also, if La Niña forms, it’s very likely this will be a weak event, with a maximum between -0.9 and -0.5 °C, in line with model predictions. In the historical record, which starts in 1950, only four La Niña events have formed this late in the year, with two forming in September–November and two in October–December. These were all either weak or on the border between weak and moderate. ENSO events are strongest in the winter, so there’s less time for this La Niña to grow from where we are now.

The strength of an ENSO event, as gauged by its sea surface temperature departures, matters because stronger events change the atmospheric circulation more consistently, leading to more consistent impacts on temperature, rainfall, and other patterns. A weaker event makes it more likely that other weather and climate phenomena could play the role of spoiler. However, even a weak La Niña can factor into seasonal outlooks, because it can still nudge the global atmosphere.

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer

Next month, Nat will review what the models have to say about winter conditions, including how much they reflect La Niña’s expected impacts. Stay tuned here at the ENSO Blog—we’re all treat, no trick!

Footnote

- The weekly SST data has been temporarily changed from OISSTv2.1 to UK Met OSTIA: https://ghrsst-pp.metoffice.gov.uk/ostiawebsite/index.html .

- ERSSTv5 has temporarily been replaced with JMA COBE2 SST data. https://ds.data.jma.go.jp/tcc/tcc/products/elnino/cobesst2_doc.html

- More on our usual temperature data in Tom’s post here.