NOAA: October 2018 ENSO Update: Trick or Treat!

By: Emily Becker

ENSO-neutral conditions still reign as of the beginning of the month, but we’re starting to see some clearer signs of the development of El Niño. Forecasters estimate that El Niño conditions will develop in the next few months, and there’s a 70-75% chance El Niño will be present through the winter. Most computer models are currently predicting a weak El Niño event.

Goblins and ghouls

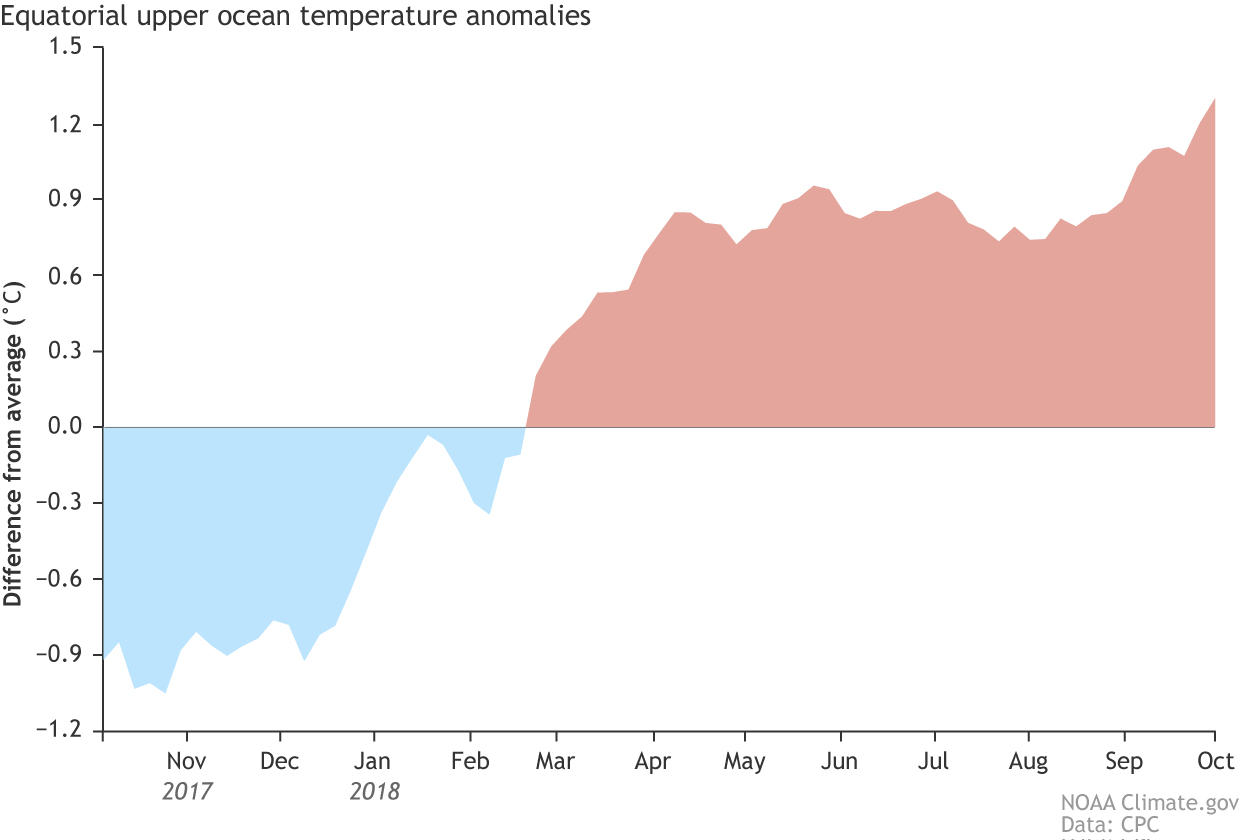

Over the past several weeks, surface temperature anomalies (difference from the long-term average) have gradually increased across much of the tropical Pacific. All four of the Niño-monitoring-region temperatures are now above average.

The temperature in the Niño3.4 region (our primary metric for monitoring El Niño’s development) was 0.7°C above the long-term average in the latest weekly measurement. Yep, that’s above the El Niño threshold of 0.5°C, but we’ll need the monthly temperature in the Nino3.4 region to average above that threshold, plus an expectation that it will stay above, and indications that the atmosphere is responding to the change in the ocean before we’d declare El Niño.

Witches and wizards

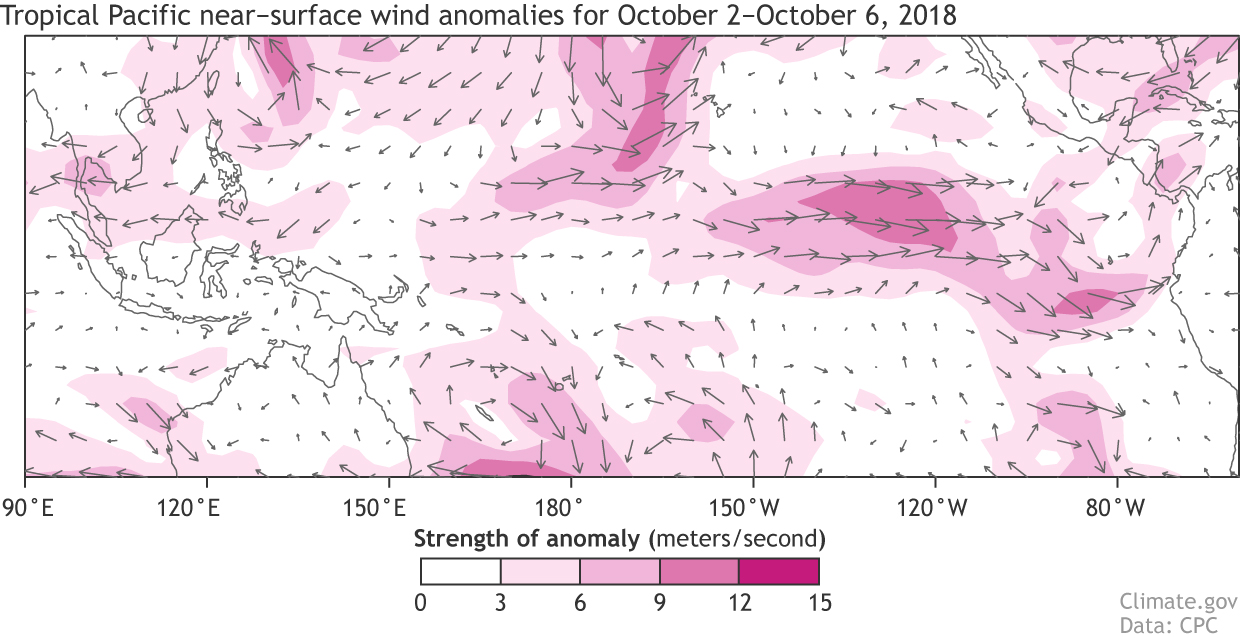

Regular ENSO Blog readers will know that we go on about the winds that blow across the tropical Pacific. At times, we probably get pretty windy about the wind! That’s because these winds are very important to the development and maintenance of El Niño and La Niña. ENSO—short for El Niño-Southern Oscillation—is a coupled system, meaning the ocean causes changes in the atmosphere and the atmosphere in turn affects the ocean.

The trade winds normally blow from east to west (“easterly” winds, in meteorological parlance) along the equator in the Pacific. They help bring colder water up from the depths of the ocean to the surface near South America and also pile up warmer waters in the far western Pacific, near Indonesia. When these winds slow down, the surface water can warm, and warmer waters from Indonesia begin to slosh eastward (a downwelling Kelvin wave). It takes a few months for the warm blob of water to travel across the Pacific, and when it reaches the coast of South America, the blob can rise to the surface, providing a months-long source of warmer water to the surface.

The reason I’m rattling on about this effect of the winds is that we’ve recently had a pretty substantial slowing down of the trade winds in the central and eastern Pacific—one of the strongest such episodes during September/October since 1979, when our real-time reanalysis data records begin.

This slowdown in the winds has already allowed the surface to warm, and will help to reinforce the warmer subsurface waters that have been developing since August. The temperature anomaly in the upper ~1000 feet of the central-eastern Pacific, elevated since the spring, has increased over the past month.

Elsa and Anna

The development of El Niño in the late fall isn’t unusual, with nine El Niño events since 1950 starting in August–October or later in the fall. Of these, only one (1986-87) had a peak Niño3.4 Index greater than 1.0 degree; all the others were weaker events. Since El Niño events peak in November or December, there probably isn’t enough time for sea surface temperature anomalies to grow very large.

The strength of El Niño doesn’t necessarily indicate the strength of its impacts on global weather. But a stronger El Niño can increase the likelihood that impacts of some kind will happen. The Climate Prediction Center’s winter outlook will be released next Thursday (October 18th), so stay tuned to see what effect El Niño may have on U.S. winter weather. We’ll also have a post here at the ENSO Blog on that outlook.