A solo skier was caught, carried, partially buried, and injured in an avalanche in Little Cottonwood Canyon on Sunday, February 11, that threw him 1,500 feet over cliffs in terrain that would almost certainly be dubbed as ‘unsurvivable’. Another ski tourer in a nearby party put himself in harm’s way to go rescue the injured skier, where then a rescue helicopter was dispatched. Below are comments from both sides; the victim, and one of the ski tourers who witnessed the event, as shared by the Utah Avalanche Center.

Observer

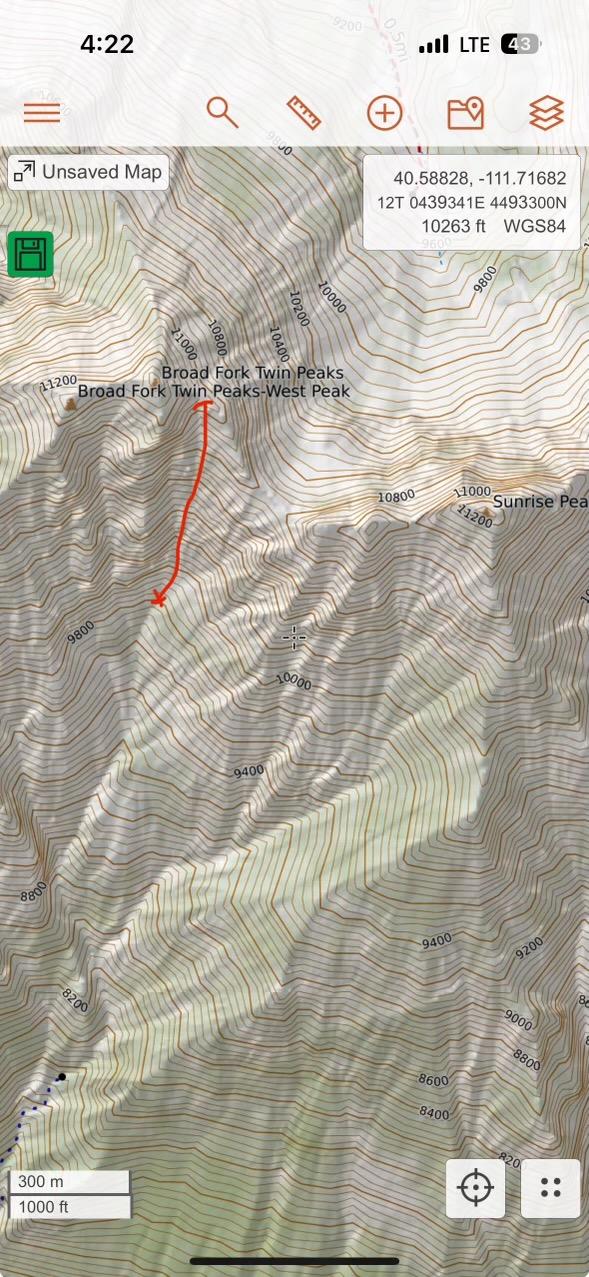

From the East Ridge of BF Twins, we watched a solo skier get caught, carried, and injured in a serious avalanche into south-facing terrain in between Lisa Falls and Jepson’s Folley. This skier followed the track that our group of three set to the col between Sunrise Peak and BF Twins, but never initiated a conversation with us to determine how our plans and theirs lined up. As we were boot-packing up the lower east ridge, this skier traversed below us in the start zone of this path into a small couloir, where they were caught and carried in a small avalanche. They continued skinning up the couloir after this and went out of sight as we continued up the ridge. As we neared the intersection of the couloir and the ridge, we noticed a pillow of wind drifted snow at the top of the couloir. Soon thereafter, this slab released on the skier skinning up the couloir. While we couldn’t see the skier at the time of the avalanche, we moved to a viewpoint where we could see the whole path, and they were not visible. At this point, one skier from our group continued to a lower viewpoint on the bed surface lower down where they made voice and visual contact with the skier in the avalanche, who requested help.

The skiers on the ridge called 911, and the lower skier in our group continued down the path to access the injured skier who was on the surface of the debris, airbag deployed, and critically injured. The skier from our party then called 911 again to provide updated coordinates and patient information. We want to extend a huge thanks to Intermountain Lifeflight and Utah DPS who performed a hoist rescue of the injured skier. As this was occurring, two large natural avalanches ran past our relative island of safety, and the skier in our party requested a hoist rescue as well due to the rapidly changing stability and avalanche activity.

This was a miracle. This avalanche ran through what anyone would consider unsurvivable terrain. PLEASE, PLEASE communicate with others when you are recreating in popular and crowded areas such as this range. If you are going to follow people into consequential alpine terrain, even if you aren’t planning to ski with them, make the effort to communicate with them. We are so grateful that the injured skier is alive, but the skier in our group who descended to help them had to choose to expose themselves to significant hazard for an extended period of time. We are all so lucky to have such incredible access to the backcountry of the Wasatch range, and none of us have any more of a right to recreate than the next person. That said, if we don’t cooperate and communicate, accidents like this will only become more frequent as the backcountry becomes more crowded.

SS-ASu-R2-D2(This avalanche entrained a significant amount of snow, the debris field was that of a D2.5 despite the small initial slab).

Victim

Several poor decisions almost killed me today. I solo toured up Broads Fork planning to look at Bonkers or Sidewinder into Mill B but ended up following the wonderful new snow all the way to the ridge of LCC. Told myself I would either continue to the summit of Twin Peaks and ski it’s east face or reverse my uptrack. A party of three ahead of me triggered a south aspect windslab off the ridge; it had real energy and should have convinced me on the spot to reverse. Instead I told myself I would traverse lower on the south facing terrain in hopes of less wind loading. Given the exposure this was a bad decision on its face but one borne of summit/powder fever. I reached the final south facing couloir between Jepsens and Twin and began skinning up it, noting increased wind loading on its west flank but telling myself I could hang to its east side, as I have in past summits of Twin. 100′ below the ridge a windslab broke wall to wall above and began to carry me.

I deployed my airbag and and self arrested, stopping approximately 300′ down. I quickly put my bindings out of uphill lock and attempted to make a swift ski exit, but another larger slide hit me at that point. I was carried at great speed another 1500′ or so; my face was submerged immediately and my airway filled with snow. While I tried to get my hand in position to clear my mouth I went airborne over a cliff, landed hard, and kept descending. When the slide stopped I remained submerged but managed to dig my face out, breathe, and begin to drag myself up and to the side of the couloir and (relative safety). I likely was concussed or mildly hypoxic from my burial as I kept thinking this was a dream for several minutes. When my head cleared a member of the earlier party of three had skied to me and begun calling for a helicopter evacuation. He helped get me warm and recover my airbag pack and I cannot stress enough that his bravery in going down to me with hangfire above was exceptional. I was barely able to speak let alone call my own rescue in a timely fashion: without his initiative I would have been in much worse shape. I was hauled by helicopter and stabilized by EMS with many broken ribs, broken facial bones, and a hemothorax.

Looking back I do not often tour solo and, when I do, I stick to mellow trees terrain. What possessed me to break that trend to expose myself to severe terrain alone and push past clear red flags is, tonight, baffling and shameful to me. I have been touring about 18 years and thought that experience would help me know better; instead, I fell prey to the restlessness that comes from a long spell of poor snow then stubborn PWL. My patience failed and I took a ride that should have killed me twice over. I deeply hope others stay safe and can wait a little longer than I could to tackle the big lines of the Wasatch.