Yesterday the Utah Avalanche Center released its full report from the fatal slide in Pole Canyon, UT, on March 27th, 2023. The findings can be a learning opportunity for all of us.

The full report is below:

Accident: Pole Canyon

- Observer Name: UAC Staff

- Observation Date: Tuesday, April 4, 2023

- Avalanche Date: Monday, March 27, 2023

- Region: Salt Lake » Oquirrh Mountains » Flat Top » Pole Canyon

- Location Name or Route: Oquirrh Mountains, Pole Canyon

- Elevation: 10,400′

- Aspect: East

- Slope Angle: 38°

- Trigger: Snowmobiler

- Trigger: additional info: Unintentionally Triggered

- Avalanche Type: Hard Slab

- Avalanche Problem: Persistent Weak Layer

- Weak Layer: Facets

- Depth: 3′

- Width: 4,500′

- Vertical: 2,250′

- Carried: 1

- Caught: 1

- Buried – Fully: 1

- Injured: 1

- Killed: 1

Accident and Rescue Summary

Two brothers, Ryan and Brett, set out with four friends to ride snowmobiles in Ophir Canyon, on the east side of the Oquirrh Mountains, 45 miles southwest of Salt Lake City, Utah. It was a familiar ride in an area where the family has a cabin and the brothers travel there in both summer and winter.

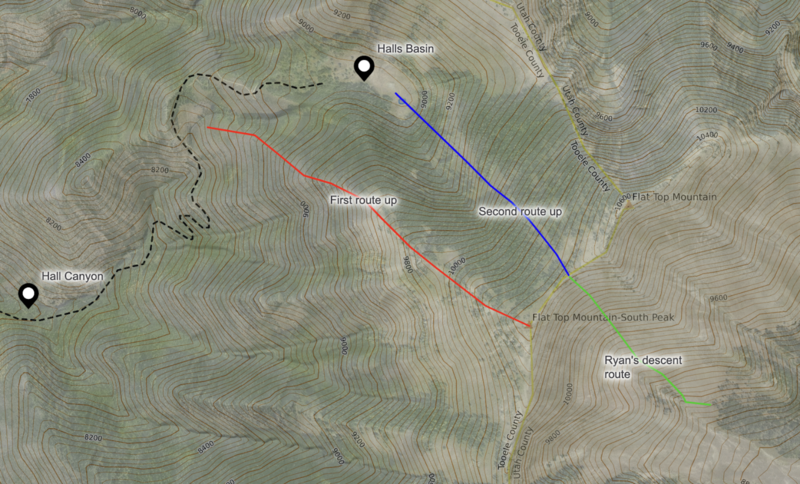

The group of six riders rode north into Ophir Canyon, turned east into Hall Canyon, and eventually rode into Halls Basin under the northwest-facing slopes of Flat Top Mountain. There is an old mailbox on Flat Top Mountain with a summit register where they like to record their visits each season. The group ascended Flat Top Mountain via a northwest ridgeline and descended the same route back into Halls Basin. They made a second attempt directly up a tree-covered, northwest-facing slope at the head of the basin. During that attempt, four people in the group had to leave before reaching the top. Brett and Ryan remained and were able to climb to the top again via the tree covered slope.

At the top, they admired the views and talked about the great day they were having. Brett called his wife while Ryan walked some distance onto the bowl that drops into Pole Canyon to assess the snow conditions. He noticed an old avalanche to the south next to Lewiston Peak. He knew that portion of the bowl avalanches regularly, and it appeared to have happened several days before. He also noticed that there seemed to be less new snow in this bowl compared to where they had just climbed. In years past, they had used alternative routes for descending into Pole Canyon. This time however, they thought the snow had stabilized since the recent avalanche and decided to descend into the bowl.

Ryan began his descent, generally staying to his left (north of) the gully below. He’d had close calls with avalanches before, and as he went over a “hump” he wasn’t feeling good about being in the bowl. He looked over his shoulder and saw a massive powder cloud barreling downhill toward him. He immediately cut to his left to escape the avalanche as was able to ride safely out of the path.

Brett began his descent at some point while Ryan was still moving, and we don’t know where he was when the avalanche happened. From aerial photos, we know that his initial descent paralleled Ryan’s tracks. We suspect he was relatively high on the slope based on his burial location. As the avalanche happened, Brett was initially able talk to Ryan on the radio saying “not good, not good,” and at some point, he deployed his canister style, ABS airbag backpack.

Ryan was lucky to escape the leading edge of this massive avalanche which ran roughly 2,360 vertical feet downhill and out of sight in the valley below. From his position on the side of the avalanche, he reported that it took some time for the debris to stop moving. He also reported seeing debris pile up in the gully below where Brett was buried. He did not know Brett was buried there at the time.

The avalanche was still moving when Ryan called 911 at 6:10 p.m. He knew it was a large avalanche and would need help. The dispatcher had more questions for him, but he hung up to descend and begin his search for Brett. As he began his search, he called the group of 4 who had been riding with him earlier in the day. None of them answered, and he sent a text message saying, “Help in Pole Canyon.” He then began his transceiver search.

During his search, Ryan descended most of the length of the debris pile, occasionally receiving ghost transceiver signals 5 to 6 meters away. He knew snowmobiles could cause interference, but thought that large digital screens now common on the newest machines were the source. He didn’t think that his older snowmobile, with a smaller, simple screen, would interfere. At some point, he realized that his snowmobile was the source of interference.

Ryan restarted his search by assessing the debris for a likely burial location, bringing him back near the head of the debris. To mitigate interference with his transceiver, he would ride approximately 50 meters, step away from his snowmobile, search for a signal, and repeat the process. When he initially acquired Brett’s signal, his transceiver read 50 meters. At that point, he moved on foot, and the lowest (or closest) reading he could get on his transceiver was between 5 and 6 meters. He began probing, but with such a deep burial, he could not reach Brett with his probe. He then began digging, followed by more probing and more digging. One challenge he faced was that the cable inside his probe would stretch or slip when he pulled it out of the very dense avalanche debris.

The Utah County Sheriff’s Office established an incident command post at the base of Pole Canyon with Utah County Search and Rescue (SAR), a Life Flight helicopter, the Division of Public Safety (DPS) helicopter, members of the Utah Avalanche Center, family members, and other groups. The first team of three from Utah County SAR were flown to the avalanche by DPS at 7:30 p.m.

As Ryan continued digging, two cousins (Evan and Eric) from the group of four riding with them earlier that day arrived shortly before the first SAR personnel. The other two friends (Ben and Wade) came a short time after. All four of Ryan’s friends accessed the avalanche by riding up Pole Canyon on snowmobiles.

At 7:40 p.m. another three SAR personnel arrived again via DPS helicopter. The last group of two SAR personnel was shuttled to the accident site at 8:10 pm, roughly two hours after the 911 call. This brought the total Search and Rescue members to eight people, along with the group of four riding partners.

One piece of equipment the group found very valuable was a Pieps iProbe, an electronic probe that can detect a transceiver signal. Without having a probe strike for some time, this tool helped direct their digging efforts.

At 8:26 pm, the friends and rescuers located Brett’s buried snowmobile. After another 22 minutes of digging at approximately 8:48 pm, they located and extracted Brett. He was found face down and partially under his snowmobile just over 4 meters deep (13.2 feet). His airbag backpack was found deflated and appeared to have ruptured at some point from pressure of the avalanche debris. After extracting Brett from the debris, paramedics worked on him for roughly 30 minutes with no success. Brett was declared deceased at 9:18 p.m.

The DPS helicopter began shuttling team members from the accident site back to the incident command center, where family awaited. Ryan and their group of four friends rode their snowmobiles out of Pole Canyon, and all people were off the site by 11:30 p.m.

Terrain Summary

Pole Canyon is located on the southernmost end of the Oquirrh Mountains with Flat Top South Peak (10,420 feet) at the head of the canyon. Pole Canyon mainly runs north and south. It has many steep avalanche-prone slopes that funnel into terrain traps and gullies formed by snowmelt and summertime water runoff. The base of the drainage is Cedar Valley, and there is a small town just east of the canyon in the foothills called Cedar Fork. Most of Pole Canyon is private land with no public access.

This avalanche fractured over parts of a bowl facing east, southeast, and south on Flat Top South Peak. This large, open bowl has very few trees or vegetation on the steep slopes. The avalanche fracture line (crown face) was 4,250 feet wide based on measurements in Google Earth and CalTopo. The avalanche ran 2,360 vertical feet downhill. The avalanche traveled a horizontal distance of 1.26 miles (6,635 feet) from the crown face to the toe of the debris. The runout (or alpha) angle was approximately 20 degrees.

The avalanche was a hard slab that piled debris deeply on specific terrain features like the steep gullies and flat benches, where we found debris greater than 20 feet deep. In areas where the debris fanned out, it was generally less than 5 feet deep. While there is little historical data for this area, conversations with one resident helped us classify this avalanche as HS-AM-D4-R4-O. This large avalanche fractured over an extensive area and broke relatively deep, creating a massive volume of snow that funneled into the deep gully below.

Weather Conditions and History

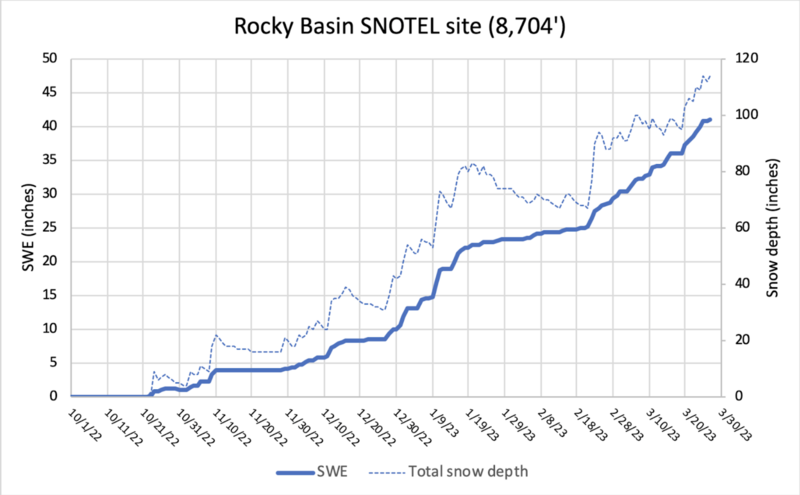

The Utah Avalanche Center does not forecast the Oquirrh Mountains, and we have minimal data for the mountain range. The nearest precipitation data comes from the Rocky Basin-Settleme SNOTEL site, which is 5.8 miles to the north-northwest.

From March 20-27th, 2023, the week leading up to the accident, this SNOTEL site recorded 3.8 inches of snow water equivalent (SWE) and total snow depth increased by 11 inches. There is no high-elevation wind data for this area; however, prevailing winds generally blow from the west-southwest (pre-frontal) and the west-northwest (post-frontal). Either case would load (add additional snowfall) this starting zone that faces mainly east-southeast.

Snow Profile Comments

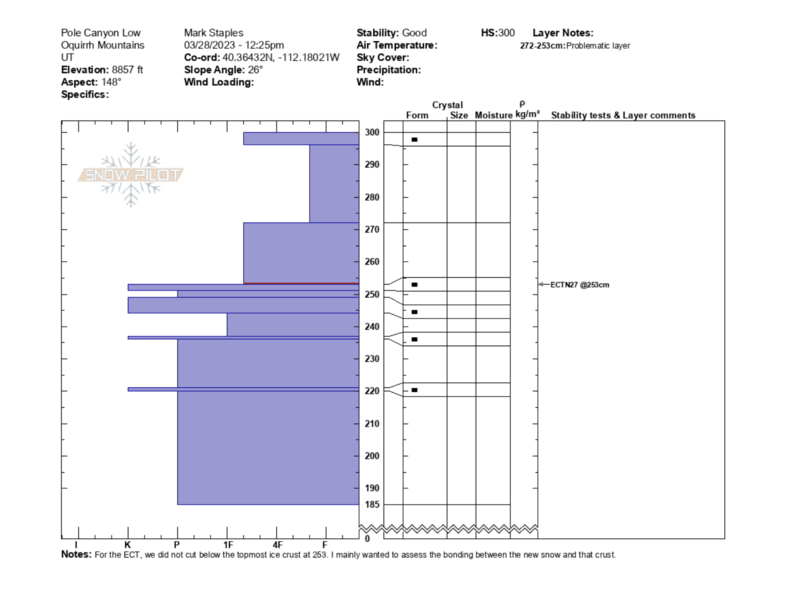

Utah Avalanche Center forecasters visited the site on Tuesday, March 28th, and recorded two snow profiles. The first profile was taken on a southeast-facing slope at 8,857 feet about 500 feet north of the avalanche track where we recorded a total snow depth of 3 meters (9.84 feet).

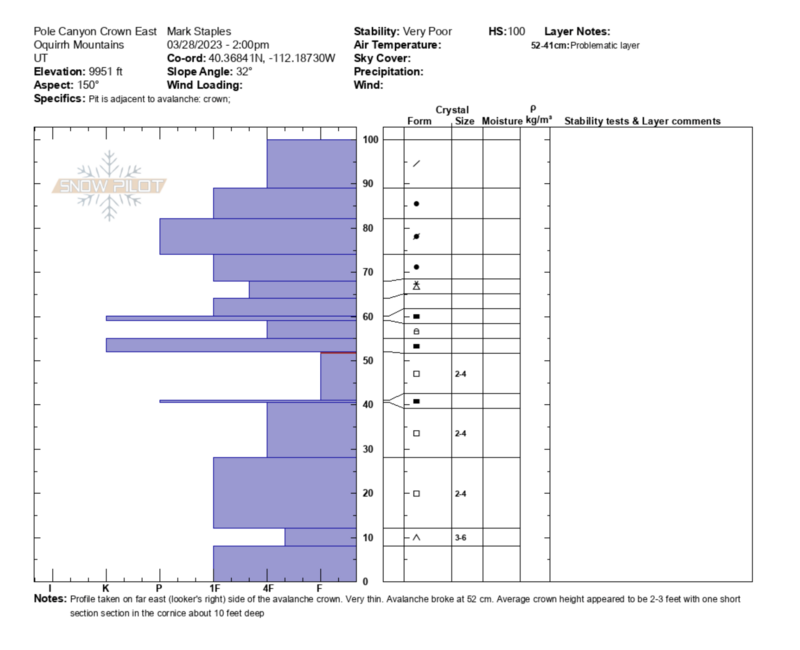

The crown profile (see overall video below) was surprising with at total snow depth of only 1 meter (3.28 feet) while it had been 3 meters deep at a lower elevations. With most parts of Utah having above average snow, 1 meter of total snow is very shallow at that elevation.

This avalanche failed on a fist hard layer of layer of faceted snow grains 50 centimeters up from the ground. The snow grains were 2-4 millimeters in size with striations usually seen on well developed depth hoar. We believe this avalanche path likely avalanched once, twice, or many times earlier in the winter, or strong winds may have stripped snow from this bowl. Scouring winds or previous avalanches or both may have contributed to a shallow snowpack. Having a shallow snowpack likely contributed to the development of this weak layer.

The slab thickness (height of the crown) measured 50 centimeters (1.64 feet) in this location, but average slab thickness was closer to 90 centimeters (3 feet deep) and had maximum depths of 10 feet where fractured into a large cornice. The bed surface revealed many rocks and bushes, further evidence of shallow snow prior to recent storms. If the snowpack had been deeper in this bowl, we would have expected to find either a thicker slab or more snow on the bed surface.

Comments

We aim to learn from accidents like this and offer comments to help others avoid future accidents. All of us at the Utah Avalanche Center has had our own close calls and know how easy it is to make mistakes. Here are some take-a-ways from this accident:

- Both brothers carried an avalanche transceiver, shovel, and probe, along with airbag backpacks and radios for communication.

- Snowmobiles are very useful tools during an avalanche rescue because they allow someone to cover long distances quickly; however, they also cause electro-magnetic interference with transceivers. Identifying and mitigating this interference is crucial. The current recommendationis to be 3 meters away from a snowmobile when searching. They can be used in the signal search phase of a rescue, but you need to stop occasionally move 3 meters away from the snowmobile. If there is no signal, return to the sled and change locations.

- Avalanche airbags can limit burial depth but are much less effective in terrain traps. Additionally, terrain traps tend to cause deep burials because the avalanche debris often accumulates deeper than it would otherwise. Deep burials are very hard to survive.

- Avalanche probes are delicate pieces of equipment and most are generally less than 3 meters long. One piece of equipment the group found very valuable was a Pieps iProbe, an electronic probe that can detect a transceiver signal. Without having a probe strike for some time, this tool helped direct their digging efforts.

- Always only to expose one person to avalanche terrain at one time. It was very lucky in this case that both riders were not buried.

Comments

We are deeply saddened by the loss of Brett Howard Warner. We hope this report can help others stay safe in the mountain by learning from it. Thank you, Ryan (Brett’s Brother), for being open and honest with us and sharing your story. Our sincerest condolences and thoughts go out to all the family, search and rescue members, and others affected by this tragedy.