Brought to you by Hakuba Valley

If you are considering booking a ski lesson on your next snow vacation, consider this: The window price for a full-day private lesson at Beaver Creek in Colorado is a whopping $1,109 (USD). Compare that to Niseko, Japan where you can get the same full-day private lesson for around $500 (USD). Both mountains boast amenities like luxury hotels and Michelin Star chefs when the skiing ends and apres begins. At 2,191 acres, Niseko is slightly bigger than Beaver Creek and receives more average snowfall. So why are ski lesson prices so much different? Niseko has 50 independent ski schools (most of them English speaking) totaling nearly a thousand instructors, all providing a variety of customizable lesson options. Ski lessons in Japan are cheaper than most places in North America because of this market competition.

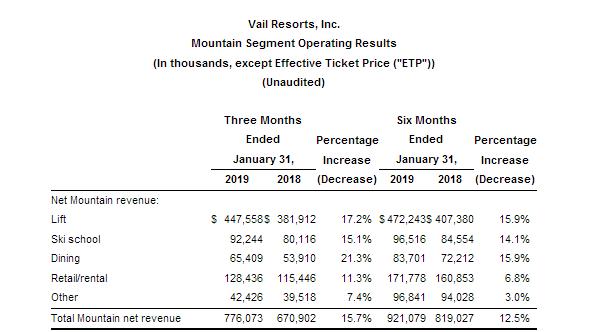

It’s no secret that ski industry giants like Vail Resorts and Alterra Mountain Company have built their snowy empires on much more than lift ticket sales. Control over products like accommodation, on-mountain dining, and ski lessons means every dollar spent by a vacationer adds to their financial success. Lift ticket sales for Vail Resorts in their last fiscal quarter was only slightly above 50% of total company revenue. The other half of their revenue comes from other services like accommodation, food, and beverage, or ski school. Over 10% of Vail revenue comes from the army of blue instructor uniforms. All resorts in North America follow this savvy business model. With so many snowsports instructors the world over, selling lessons is a lucrative business.

Because the American, Canadian, and Australian ski resort business model allows a monopoly of services on a mountain (even when leased from public land), resorts in these places have a captive customer base. Want a quick burger or pizza while on the mountain? So does everyone else. The prices at the mountain-owned cafeteria will likely be double what you would pay anywhere else. The same is true with ski lessons. Enter Japan. In a remarkable business oversight, most Japanese resorts are not run on the same monopoly principle. Much like their European counterparts, Japanese lift operating companies are distinct from other mountain services like ski schools. With multiple independent ski schools all competing for more customers and good reviews, the price of lessons stays competitive, which is good news for consumers. It also means more choices. Some boutique ski schools in Japan offer concierge service at exclusive prices, but there is always a less expensive option.

The Japanese system is not without its drawbacks: since the glory days of Japanese skiing in the ’80s, there has been a decline in domestic skiers within Japan. This has caused some of Japan’s 500 ski resorts to struggle. Without additional sources of revenue from an all-inclusive ski vacation package, the lift operators can only survive if more people buy lift passes. The most successful resorts have been the ones in Niseko and Hakuba that tap into the growing international ski market. Other resorts in Japan are following, some even offering one-day-free deals to international travelers as a way to grow their skier base. At the end of the season, Japan’s resorts have no chance of making it onto Forbes list of fastest-growing ski companies.

But that is good news for consumers of snow. A high supply with a low demand means lift ticket prices and lesson prices stay low. Even in Niseko and Hakuba where demand is high due to international visitors staying in luxury ski-in, ski-out accommodation, competing ski schools offer deals, promotions, and customized lessons to attract aspiring snow enthusiasts. Added to this, the qualifications of English-speaking instructors who work seasonally in Japan’s popular destinations are on average higher than most ski schools in the U.S. Vail Resorts can pay a young, uncertified instructor $72 per day (before tax) while still charging guests over $1,000 per day because aspiring skiers don’t know to ask for an experienced instructor, and veteran instructors are dwindling as wages dwindle. English speaking instructors in Japan, on the other hand, can simply start their own ski school if they feel like their wages with the established ski schools are not fair. Because of this, the bigger international ski schools in Japan often pay experienced instructors nearly double the hourly rate of ski schools in the U.S. or Canada. Mountain-goers can feel good paying less for their lesson knowing their instructor is getting paid more than the US average.

The U.S. and Canadian business model under which ski schools are run in North America tends to increase prices and limit consumer lesson product choices. This monopolized system has been extremely successful from a business standpoint because the resort can cash in on every dollar spent from the moment ski vacationers arrive until they leave. It also offers a convenient one-stop-buys-all vacation package for those looking for a stress-free holiday. In contrast, visitors to Japan’s ski resorts can shop for the best deal from a variety of on-mountain vendors, including ski schools. This keeps lesson prices cheaper, instructor wages competitive, and gives skiers more lesson options.

How can I get in touch with Brian Carpentier?

Funny how perspectives change – I came here trying to find somewhere in Japan that offered lessons at what I would consider a semi-reasonable rate in comparison to Europe. This year I booked 6 days of 2 hour lessons for my 5 year-old for €155 total at a top Italian resort (as bi as anything in whole of N America and bigger than anything in Japan). I couldn’t believe it when I saw prices in Japan at €70+ for a single group lesson (particularly given lift pass prices and accommodation is perfectly reasonable).

I understand your point on monopolies but in Scandinavia they also operate like that and yet offer reasonably priced lessons (particularly when you consider the general cost of living there). So I guess it also comes down to what social demographic skiing is targeted at in each country.