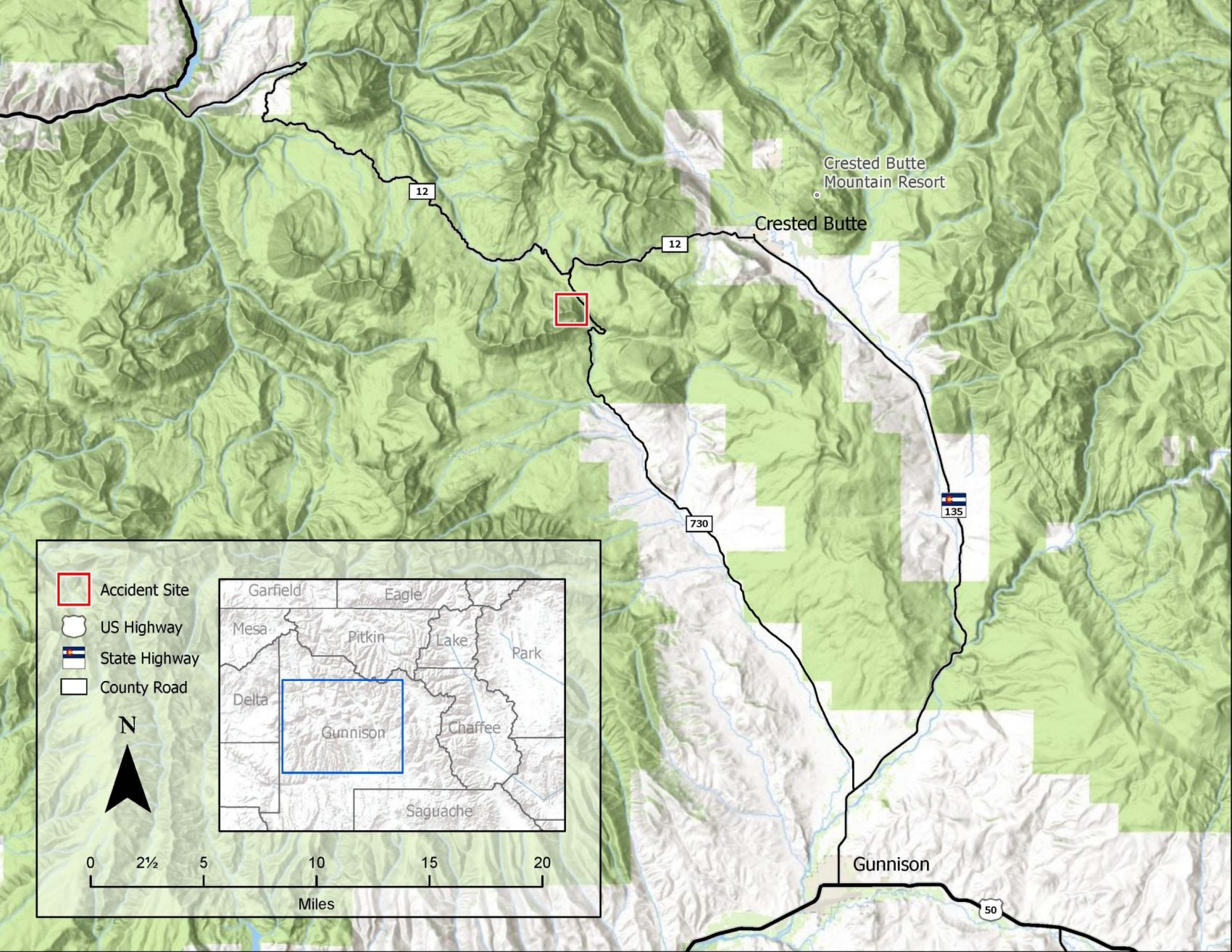

On Friday, December 18, 2020, a backcountry skier was caught, buried, and killed in an avalanche in the Anthracite Range west of Crested Butte, CO. The death was the first avalanche death of the 2020/21 season in the US.

The final accident report is now available for us all to learn from.

Avalanche Details

- Location: Near Ohio Pass, Anthracite Range

- State: Colorado

- Date: 2020/12/18

- Time: 12:30 PM (Estimated)

- Summary Description: 1 backcountry skier caught, buried, and killed

- Primary Activity: Backcountry Tourer

- Primary Travel Mode: Ski

- Location Setting: Backcountry

Number

- Caught: 1

- Partially Buried, Non-Critical: 0

- Partially Buried, Critical: 0

- Fully Buried: 1

- Injured: 0

- Killed: 1

Avalanche

- Type: SS

- Trigger: AS – Skier

- Trigger (subcode): —

- Size – Relative to Path: R2

- Size – Destructive Force: D2

- Sliding Surface: O – Within Old Snow

Site

- Slope Aspect: NE

- Site Elevation: 10535 ft

- Slope Angle: 35 °

- Slope Characteristic: Planar Slope, Sparse Trees

Avalanche Comments

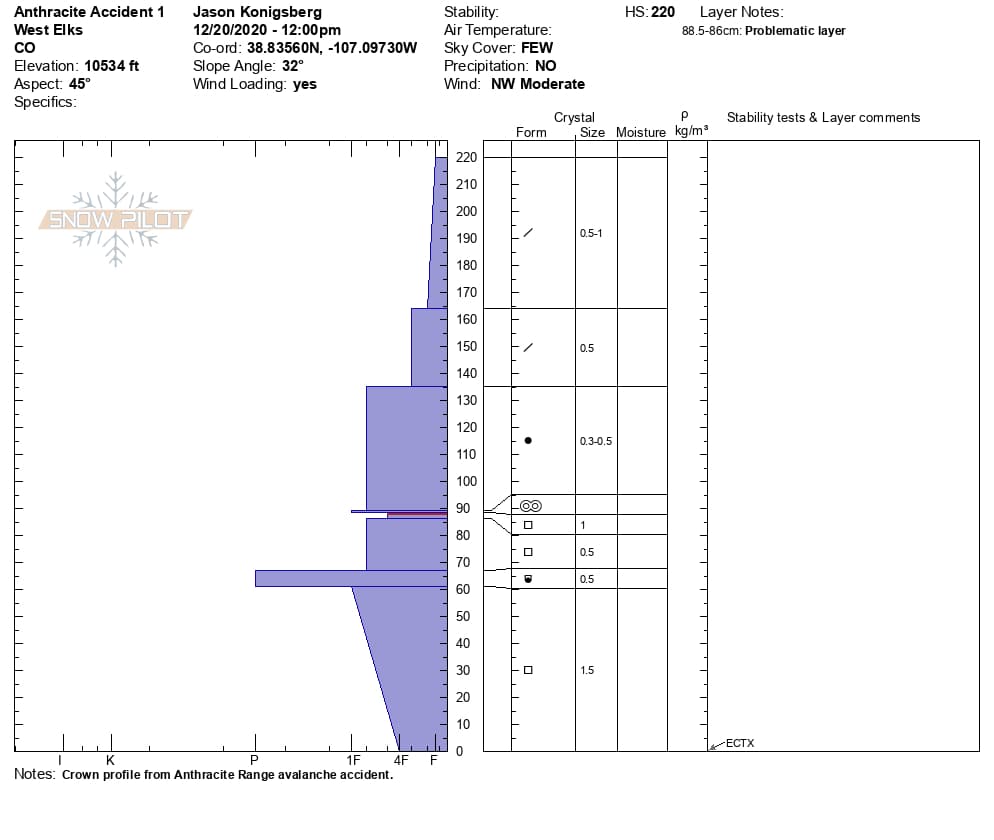

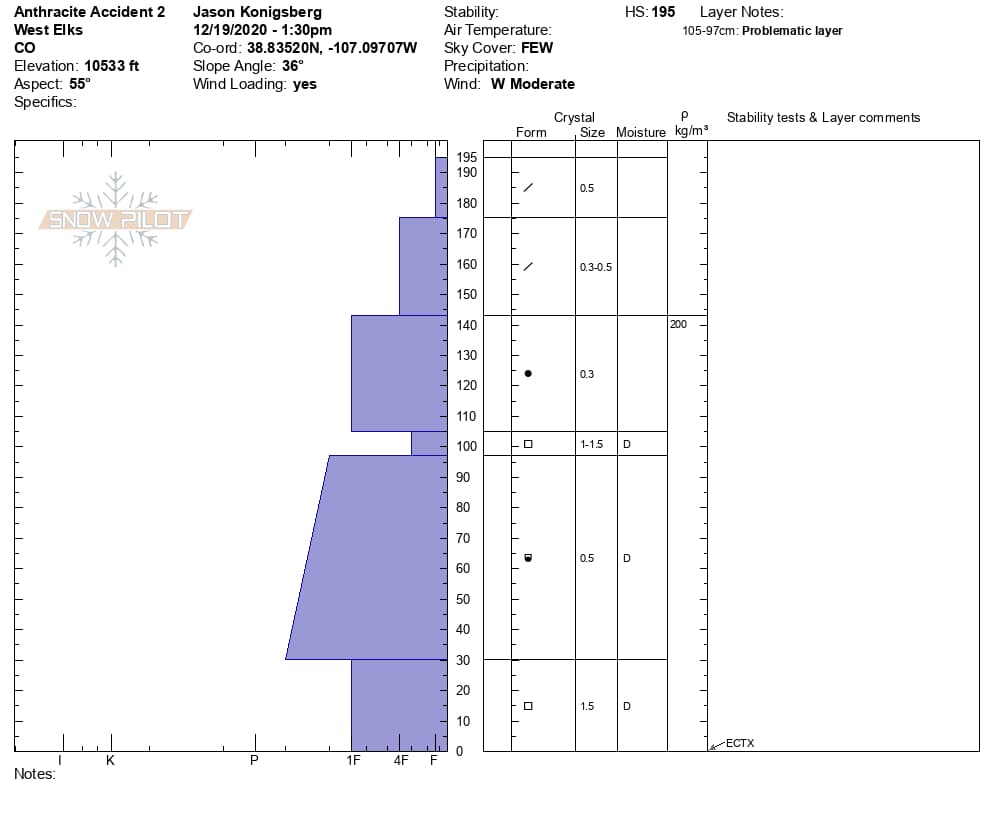

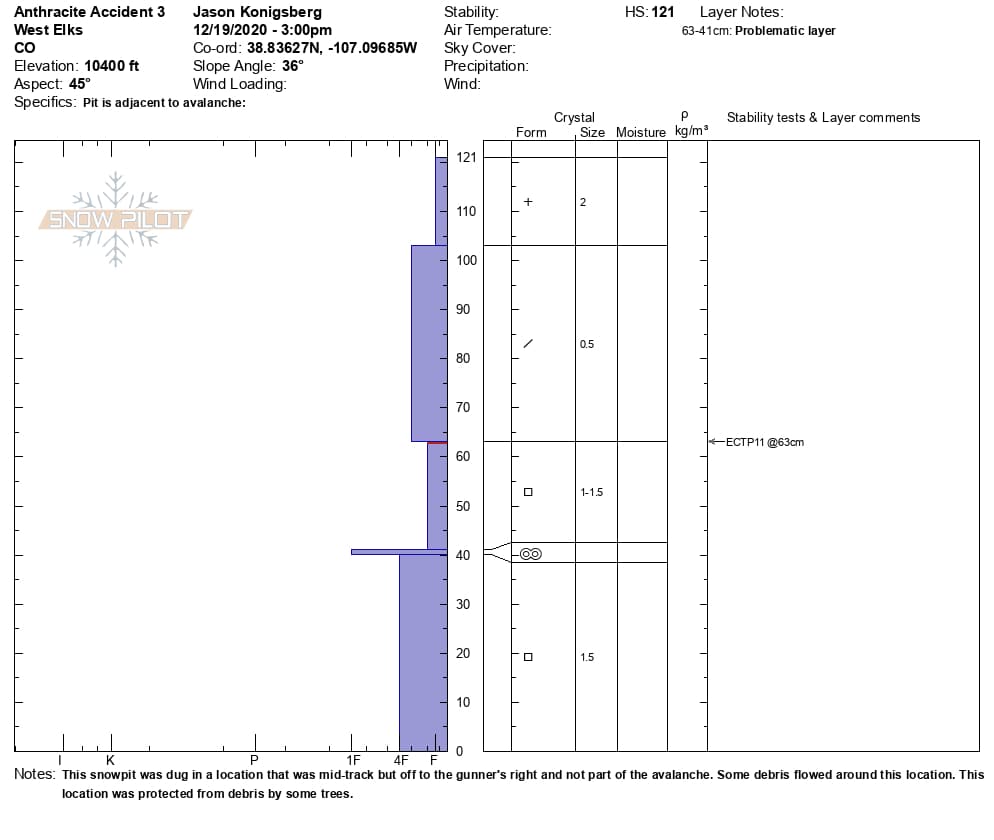

This was a soft slab avalanche triggered by a skier. The avalanche was small relative to the path and destructive enough to injure, bury, or kill a person. The avalanche failed on an old layer of faceted snow (SS-AS-R2-D2-O). The crown face of the avalanche was 3 to 7 feet deep, 400 feet wide, and the debris ran about 400 feet. At the crown of the avalanche the faceted snow layer was three to seven feet below the snowpack surface. One hundred vertical feet down slope from the crown face, the snowpack was shallower, not wind affected, and the weak layer was only two feet from the surface. This was a Persistent Slab avalanche.

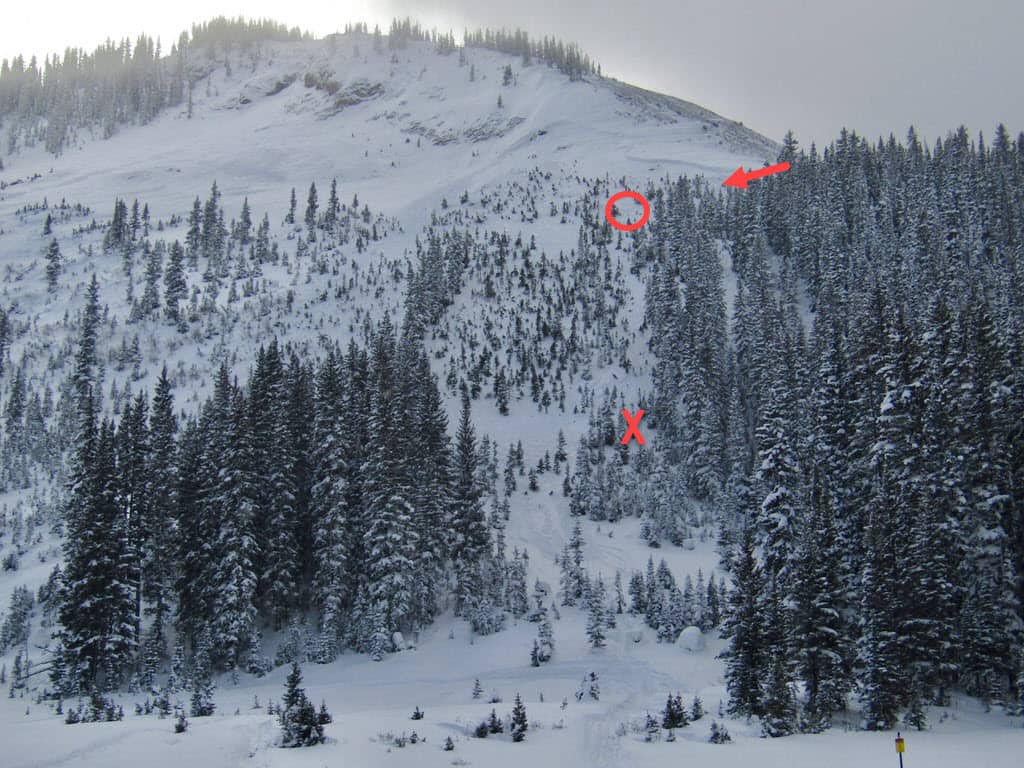

The avalanche occurred on a steep, northeast-facing, below-treeline slope. The terrain characteristics of this slope result in intense drifting of snow onto the slope with northwest winds. The amount of wind-drifted snow that this slope receives is uncharacteristic of similar slopes in this area. On December 19, as investigators conducted a crown profile, the wind was drifting large amounts of snow into the start zone. The investigators did not observe any drifting snow in other surrounding terrain.

Backcountry Avalanche Forecast

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center’s (CAIC) Gunnison zone rated the avalanche danger as Considerable (Level 3) near and above treeline, and Moderate (Level 2) below treeline.The forecast listed Persistent Slabs as the primary problem at all elevations on west through north to southeast-facing slopes. The likelihood of triggering was Likely and the potential size was Small to Large (up to D2). The summary statement read:

Dangerous conditions exist. You can trigger avalanches that break at the ground on a variety of slopes from west through northeast to southeast. In these areas, recent winds drifted snow to create thick slabs 1 to 2 feet deep. The danger is greatest in the western portion of the zone where more snow has fallen over the last week.

Treat any steep slope where you see evidence of recent wind loading as suspect. Obvious signs of recent wind loading are smooth rounded pillows of snow, cracking and collapsing in the surface snow, and small drifts on the lee side of ridges or trees. Investigate all steep slopes carefully before riding. If you trigger an avalanche today it can be large and dangerous.

You can avoid avalanches by traveling on low-angle slopes less than 30 degrees that are not below or adjacent to steeper slopes.

The Backcountry Avalanche Forecast issued by the Crested Butte Avalanche Center (CBAC) rated the avalanche danger as Considerable (Level 3) for all elevations. Their forecast highlighted “Slab avalanches remain reactive to human triggering. More natural avalanche activity is also possible…on wind-loaded slopes at mid and upper elevations. Cautious route-finding and conservative decision-making are key for backcountry recreation. Many slopes…are prime for human triggering.”

Weather Summary

After a series of early season storms, a period of dry weather began on November 23. Apart from one day of light snow showers on December 1, this period was characterized by warm days, cold nights, clear skies, and calm to light winds.

The weather pattern changed on December 10. The first in a series of winter storms brought 19 inches of snow and 1.3 inches of snow water equivalent (SWE) measured at the Irwin Guides Study Plot (3.6 miles north at an elevation of 10,420 feet). West-southwest winds at the Scarp Ridge weather station (4.6 miles north at an elevation of 12,000 feet) averaged between 10 and 20 miles per hour, with gusts into the 30s.

Two weaker storms on December 12 and December 14 added an additional 8 inches of snow and 0.5 inches of SWE. Winds were light to moderate out of the southwest, then became strong from the north. Temperatures were normal for the season, with highs averaging upper teens to low 20’s and lows generally in the single digits. The weather was calm and clear on December 16 and 17. The December 17 daytime high temperature of 33 F was the warmest of the week.

Snowfall started again on the night of December 17, with 10 inches of snow and 0.5 inches of SWE by the morning of December 18. An additional 2 inches of snow fell during the day with 0.1 inches of snow water equivalent. Southwest winds were initially 20 mph, gusting to 40 mph, and decreased to 5 mph with gusts in the low teens during the day on December 18. Temperatures gradually declined overnight and were around 20 F through the day on December 18.

Snowpack Summary

Storms during the second and third weeks of November resulted in a homogenous snowpack approximately two to three feet thick across the accident site. On December 1, a few inches of low-density snow fell without wind, and faceted very quickly. The snow surface during the dry weather developed into an exceptionally fragile layer of near surface facets (Fist hard, 1.5 mm in size). This would ultimately become the failure layer in the avalanche.

Snowfall and winds starting on December 10 formed a slab above the weak, faceted snow. There were numerous natural and human triggered avalanches on similar aspects to the accident site every day between December 10 and 18.

The avalanche starting zone is downwind of an unusually wind-exposed area. Wind-drifted snow across the starting zone was thicker and denser than surrounding terrain. The slab averaged about four feet thick across the starting zone. Further downslope in more wind-sheltered terrain the slab was thinner and softer.

Events Leading to the Avalanche

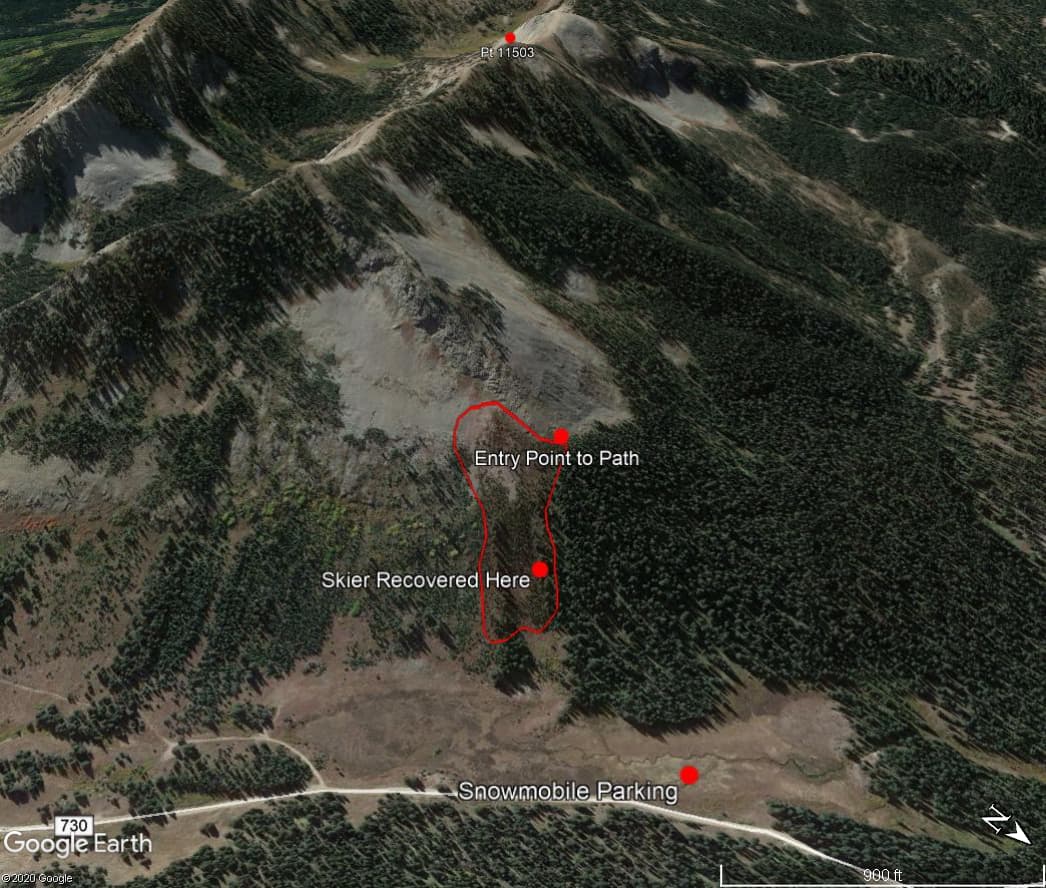

On the morning of December 18, Skier 1 snowmobiled to Ohio Pass and began ski touring some time between 8:00 AM and 10:00 AM. A party of three skiers (Skiers 2, 3, 4) arrived later. Several other parties were also ski touring in the area. Skiers 1 through 4 converged, by chance, around noon at a high point (11,503 ft) southwest of the slope that later became the accident site. Skier 1 told the others that he had already skied three runs. He also told them he planned to ski down to his snowmobile and return to town to go to work.

After encountering Skier 1, the Skiers 2, 3, and 4 skied a run north of the high point. They skinned back to the ridge before descending towards their parked snowmobiles. They looked into the top of a slope locally known as “Friendly Finish” and saw a large, recent avalanche. They descended a densely treed slope to the west of the avalanche. When they arrived back at their snowmobiles, they noticed that Skier 1’s snowmobile was still parked. They thought that something wasn’t right as they knew of Skier 1’s plans to return to town.

Rescue Summary

Skiers 2, 3 and 4 snowmobiled to the bottom of Friendly Finish and then put skins on and began to search for Skier 1. They started a transceiver search in the avalanche debris and located Skier 1 around 1:40 PM. The avalanche buried Skier 1 two to three feet deep. They extricated Skier 1, but tragically he did not survive the avalanche. Skier 4 snowmobiled to the trailhead to call for help.

Skiers 2, 3 and another skier that arrived at the site, snowmobiled Skier 1’s body to the trailhead where they were met by Crested Butte Search and Rescue and local authorities.

Comments

All of the fatal avalanche accidents we investigate are tragic events. We do our best to describe each one to help the people involved and the community as a whole better understand them. We offer these comments in the hope that it will help people avoid future avalanche accidents.

Skier 1 was a very experienced backcountry skier. He also ski patrolled for over 40 years only recently retiring from the job. Skier 1 often traveled by himself. With the amount of experience that Skier 1 had, it is safe to say that he knew the increased risk of traveling alone and accepted that risk. He was wearing an avalanche transceiver and was carrying a shovel and probe. Skier 1’s transceiver did not help him survive this accident, but it did help the rescue party conduct a swift recovery and prevent a large and extended recovery effort. From the timeline of the accident, Skier 1 could have been buried for as long as one hour before being recovered.

Skier 1 entered the slope below the obviously wind-drifted area. He likely triggered the avalanche where the recent snow was shallower and softer. Skiers 2 and 3 noted six ski tracks on the slope to the skier’s left, closer to the denser tree cover. Skier 1’s tracks were the rightmost, furthest from the trees. The avalanche took out all seven sets of tracks.The difference between getting caught in an avalanche and descending a slope without incident can be a matter of feet. The six previous ski tracks were not very far left of where Skier 1 descended. Persistent Slab avalanches are notoriously tricky and often break wider than other avalanches. At times people can travel over them without incident, before someone finds the right spot and triggers an avalanche that takes out the entire slope. Many backcountry users, including avalanche professionals, have been caught off guard by the surprising and unpredictable ways that these avalanches propagate. This type of avalanche problem requires a wide margin for error.

Media

Images

Snowpits