The 2020-2021 avalanche season has been significant on multiple levels. Most notably, it has had a historic death toll of 36 people in the United States as of March 31. Avalanche incidents have become popular in the mainstream media, and survivors face a dilemma in sharing their incidents. Reporting observations, accidents, and incidents are primary ways avalanche professionals advance the science and help save more lives.

According to the Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC),

“Over the last 10 winters an average of 27 people died in avalanches each winter in the United States. Almost every fatal accident is investigated and reported, so the CAIC can present fatality data with some certainty. There is no way to determine the number of people caught or buried in avalanches each year, because most non-fatal avalanche incidents are not reported.“

There are two sides to sharing about your avalanche incident on social media: 1) the person who shares and 2) the viewers. The person sharing has the opportunity to keep their incident to themselves even though sharing could save others’ lives. The viewers have an opportunity to like, comment, or share incidents with their personal opinion attached.

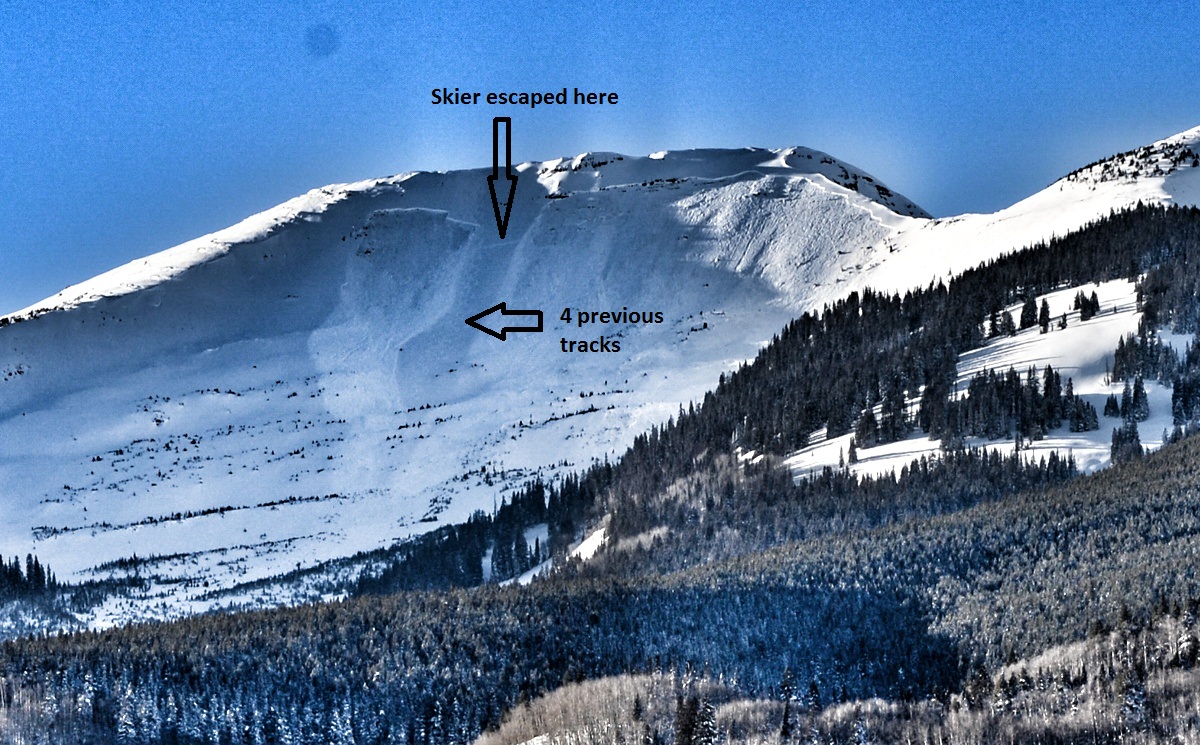

You and your regular touring partner decided to go out for a ski tour, make some controversial decisions, and end up triggering and getting caught in an avalanche (R2D2). One of you is buried up to the waist, and the other is not caught – both of you ski away slightly shaken up. After debriefing, you now can see some red flags in your decision-making process and feel sharing your story could help others not make the same mistakes. You share your incident with the CAIC and are unsure if you should share it on social media. You and your tour partner are apprehensive due to the comment superstorm of why they made bad decisions. You decide it is worth posting and put your reputation on the line. The comment superstorm soon follows, criticizing your decision-making rather than thanking you for sharing or giving polite, constructive criticism.

We must share as many incidents and close calls as possible. Many likely go unshared due to the “social media comment superstorm.” I believe part of the solution to get more individuals to share is changing the persona of comments from (generally) insulting to informative and educational. If you choose to comment, comment something polite, constructive, and informative. It does not help anyone to shame others for their risk management decisions. What could avalanche centers learn if all avalanches were reported?

Drew Hardesty, a forecaster at the Utah Avalanche Center, discusses “Shame and the Social Contract” in the Utah Avalanche Center Podcast. The podcast says:

“For most of us connection, being part of the fabric of the community, is important. We yearn for the trust and respect of our backcountry partners, friends…even loved ones. And this is central – even foundational – to how we see ourselves and dare-I- say-it, “where we fit and stack up in the community.” Reputations take a lifetime to develop, and only a few minutes to destroy. One of the things that rips apart the fabric of the community is something called Shame. What is Shame? The TedX darling and PhD-holding social worker Brené Brown describes Shame as “the intensely painful feeling or experience in believing we are somehow flawed and unworthy of acceptance and belonging.”

Given how people feel shamed for making a mistake, it makes sense if you do not want to share. We are all human and have all made mistakes.

The “Human Factor” of traveling in avalanche terrain can be thoroughly dissected to provide more insight into most avalanche incidents. Much of the time, something in this category is what individuals are bullied for – falling into a heuristic trap. Often avalanche centers analyze different heuristic traps and can point out where and when they occurred. Someone could have been exhausted at the top of a peak and subconsciously took one of these decision-making shortcuts. These are honest mistakes we should learn from, not shame.

Bruce Tremper’s Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain chapter on “The Human Factor” quotes:

“We are imperfect beings. No matter what you know or how you operate 95% of your life, you’re not a perfect person. Sometimes those imperfections have big consequences.”

-Mary Yates, widow of a professional avalanche forecaster who, along with three others, was killed in an avalanche they triggered in the La Sal Mountains of southern Utah.

As an online audience, it can be difficult to avoid judgemental conclusions regarding decision-making and risk management. Should a seasoned avalanche professional be judged by one mistake they made in their successful career? By shaming others’ mistakes online without putting yourself in their shoes, you fall into the attribution bias.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1jBAetCVYwc

According to Science Direct, “attributional bias refers to negative interpretations of other people’s behaviors, and the tendency to assign malevolent causality to ambiguous interactions.” Keep situational factors and intrinsic human nature in mind before you leave your next harsh comment.

Humans inherently make mistakes. The most seasoned avalanche professionals have had close calls and admit their mistakes. If we treat commenting as we treat the debrief, it will be much more effective. Continue to make good decisions in the backcountry, although if you end up making a bad call share it. When someone shares their close call, thank them for doing so.