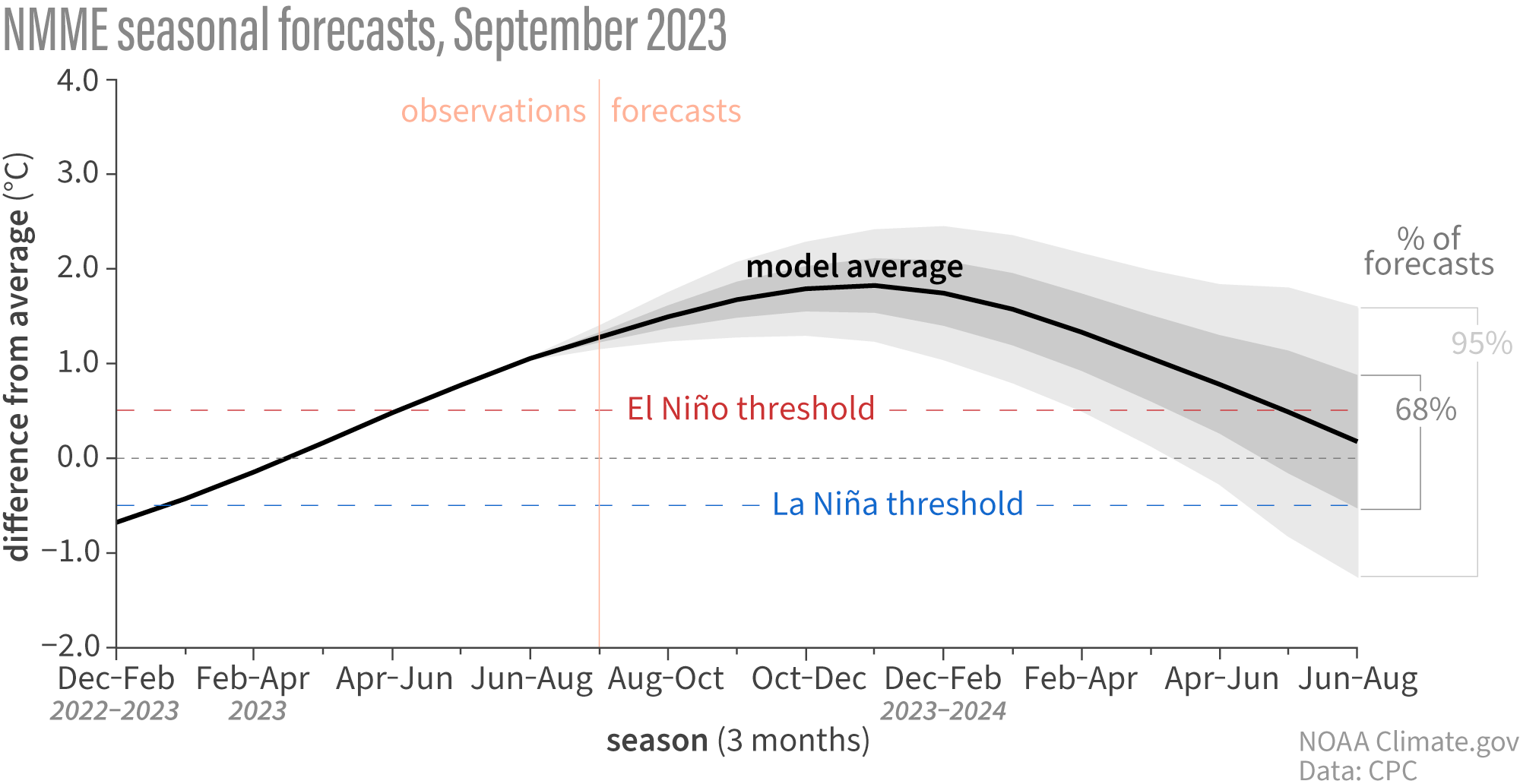

Let’s cut right to the chase. According to the September El Niño-Southern Oscillation (aka ”ENSO”) Outlook, El Niño is expected to stick around (with greater than a 95% chance) at least through January-March 2024. There is now around a 71% chance that this event peaks as a strong El Niño this winter (Oceanic Niño Index ≥ 1.5 ˚Celsius). Remember, though, a strong El Niño does not necessarily mean strong El Niño impacts locally. Instead, it means a stronger chance that El Niño impacts will occur.

Let’s dive deeper into what’s going on across the Pacific in a patented ENSO Blog expert Q&A. And boy, oh boy, are you not going to believe who we were lucky enough to snag. Without further ado, introducing our two “experts”: the Pacific Ocean and the tropical atmosphere.

ENSO Blog: Let’s start in the water. Pacific Ocean, big fan. Can you go over what “you” have been up to in the last month?

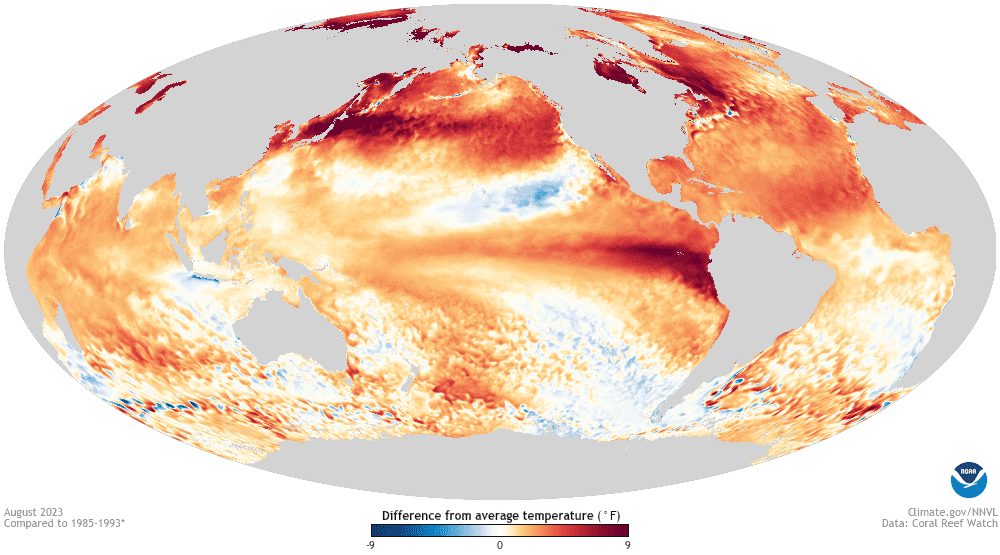

The Pacific Ocean: Hey, right back at you! It’s flattering that you have an entire blog dedicated to things going on in me. But let’s focus on what’s going on at my waist, what you call “the equator.” The main El Niño monitoring metric, the Niño-3.4 index—the average sea surface temperature in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean—was 1.3˚Celsius (2.3˚Fahrenheit) above the long-term average in August, up from 1˚C in July, according to the most reliable dataset, ERSSTv5 (long-term here is 1991-2020.) And the June-August Niño-3.4 index was 1.1˚C above the long-term average, making it the third consecutive three-month period in El Niño territory. And from what I’ve read on your blog, that means you are two more seasons away from an official “El Niño episode” in the historical record (the red in this table.)

Plus, judging from your weekly sea surface temperature datasets of my belly, the Niño-3.4 temperature anomalies are even higher during the first part of September, up to 1.6˚C.

EB: That’s pretty hot!

The Pacific Ocean: I’m pretty hot all over. In fact, my cousins the Atlantic, Indian, Arctic, and Southern Ocean are all pretty hot at the moment. Like record-breaking hot from April till now. So hot that the warmer-than-average ocean temperatures associated with El Niño happening in my central/eastern mid-section do not nearly stick out in the global picture as much as events in the past. It’s bonkers, if you ask me. The whole ocean was over 1˚C above the 20th-century average in August, the first time that’s happened in the 174-yr record. All us oceans have a fever!

EB: As we all know; El Niño doesn’t work if the atmosphere isn’t also playing. So, my next question is for the tropical atmosphere. What’s going on with you?

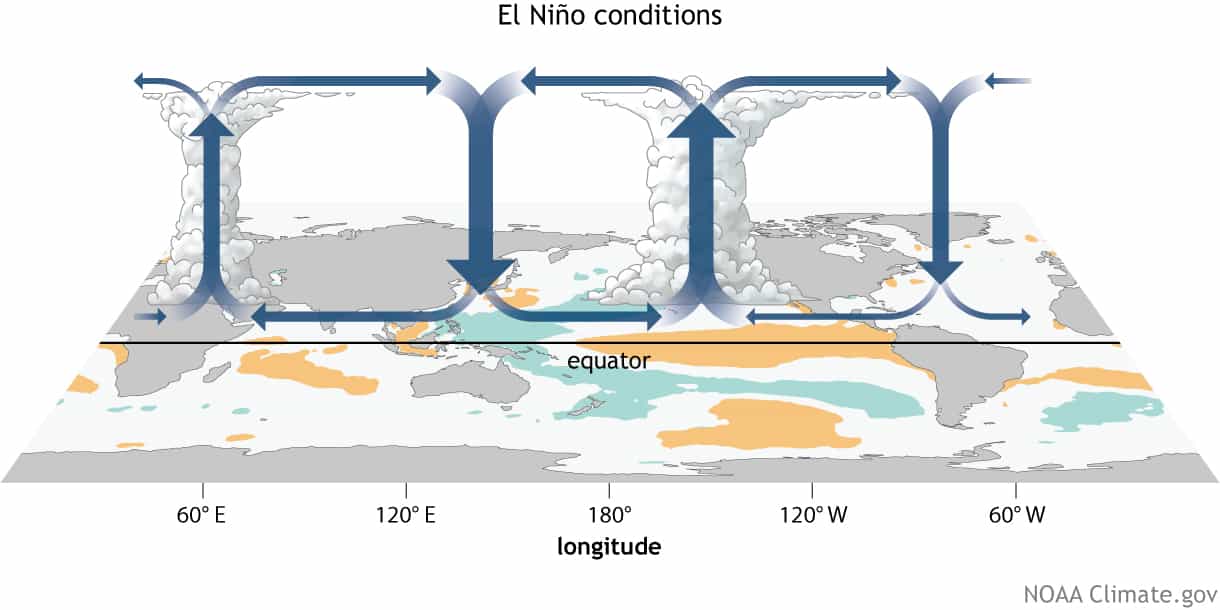

The tropical atmosphere: Thanks for having me. First-time guest, long-time reader. Believe me, El Niño’s got me all topsy-turvy. Normally when my Walker Circulation is acting like a well-oiled machine, there is rising, moist air over the warm western Pacific Ocean, sinking air over the eastern Pacific, and winds connecting those two branches: trade winds blowing east to west at the surface and west-to-east winds high up in the atmosphere. El Niño messes all of that up. And that’s what has been going on.

In August, the trade winds were weaker over the east-central equatorial Pacific. More thunderstorm activity than normal occurred farther east, extending from the international date line to the eastern Pacific Ocean, which is totally not where these storms typically reside. And then two important atmospheric metrics that you humans use, the Equatorial Southern Oscillation Index and the Southern Oscillation Index—which monitor how the surface air pressure changes between the western and eastern Pacific part of me—both were strongly negative in August, indicating an El Niño-like weakening of pressure in the eastern Pacific and higher than normal pressure in the west.

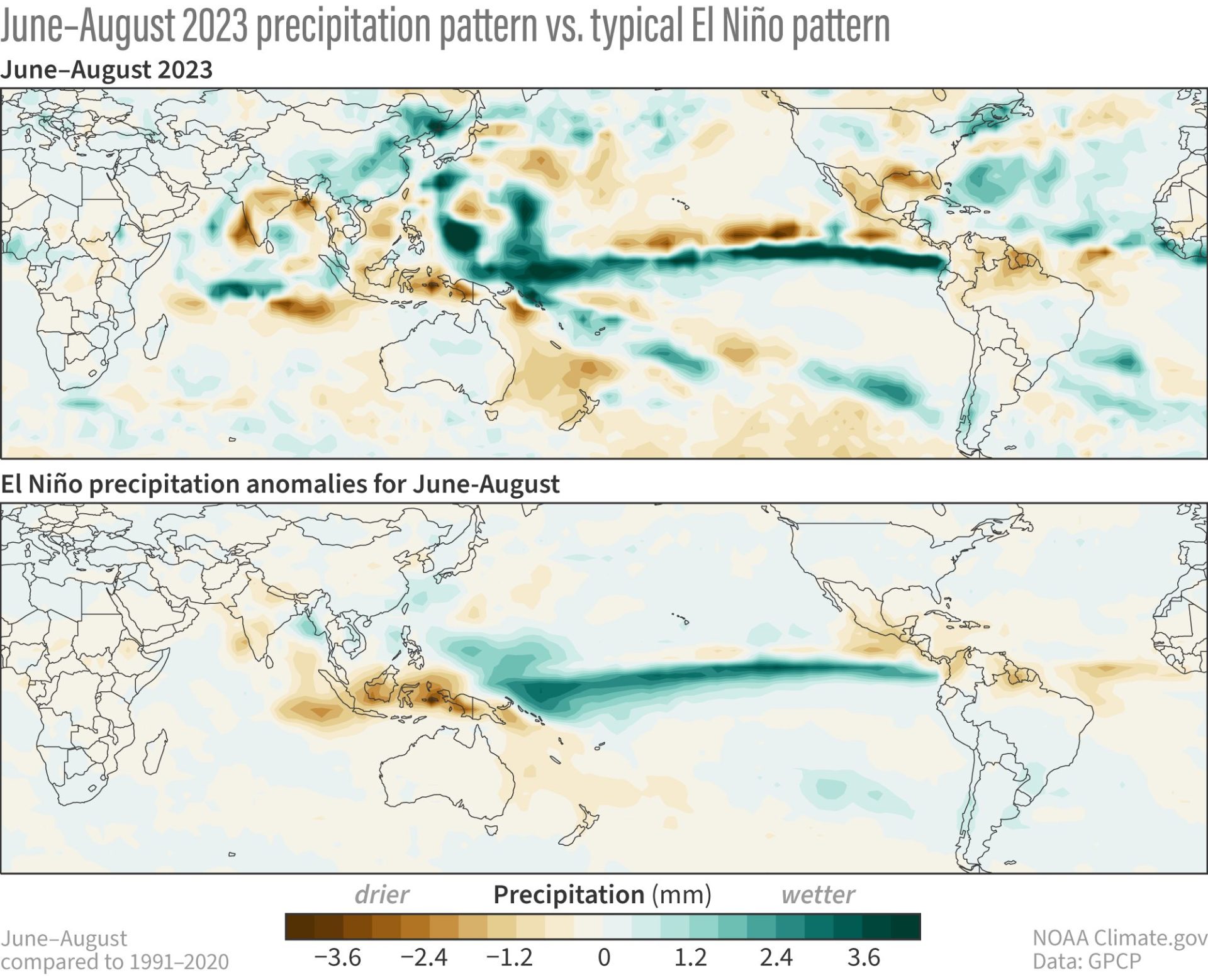

EB: How similar have recent precipitation patterns been to El Niño?

The tropical atmosphere: Take a look at these images comparing the global precipitation anomalies from June-August 2023 to how I typically behave during El Niño. Oh, I’ve been very El Niño-like! Not only has precipitation been above-average across the equatorial Pacific Ocean, but it has also been below-average over northern South America, Central America, and parts of Indonesia and India.

Now, it’s not a perfect match. I know, I know…you’ll call me unreliable. Flighty. Chaotic, even. I prefer to say that I, the tropical atmosphere, never repeat myself. I give each El Niño its own special touch. Still, this year’s rainfall patterns are pretty close to previous years’ El Niños. In fact, based on a measure of pattern similarity between these two images, out of the 11 El Niño summers on record, June-August 2023 was the third-best match to what you all call the classic El Niño pattern (footnote #1). Only the summers of 1997 and 2015 were more like El Niño. Remember those events? Pretty big El Niños. So yeah, you could say that El Niño is having an impact on me.

The Pacific Ocean: How about we ask you a question now? ENSO Blog writer Tom, what can we, the Pacific Ocean and tropical atmosphere, expect from El Niño for the rest of the year?

Tom: Well, that’s a first. But great question! The global climate models we rely on are pretty certain that the currently observed warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures will last and even strengthen through winter 2023–24. After which, this El Niño event is expected to weaken, which is normal for these types of events.

The continued model confidence is one reason why forecasters have odds of over 70% that the current event will peak as a “strong” El Niño (Niño-3.4 index values greater than 1.5˚C) for the November-January average. There is even a 30% chance that Niño-3.4 values exceed 2.0˚C by this winter, which would put ocean temperatures in a tier with some of the strongest El Niños since 1950.

But to our readers, a few reminders from the ENSO Blog archive.

- You cannot blame EVERYTHING on El Niño.

- No two El Niños are alike, and the same goes for their impacts. And,

- Just because a strong event is forecasted does not necessarily mean strong impacts. Instead, El Niño can increase the chances for certain types of extremes.

That about does it for this month’s post on the ENSO Outlook. A special thanks to the Pacific Ocean and tropical atmosphere for taking some time out of their chaotic days and answering a few of my questions.

The Pacific Ocean: Of course! [waves goodbye]

The tropical atmosphere: An honor to be invited. [Blows a kiss]

Footnote

- If you look at the spatial (pattern) correlation coefficient between the two images, the coefficient is ~0.6, meaning that about 36% of the global spatial variability is explained by El Niño. This is a pretty large number as far as these things go!

This post first appeared on the climate.gov ENSO Blog.