Lou Dawson, the first person in history to ski down all 54 of Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks, published his first backcountry ski guidebook in 1985 when he was healing from an injury he sustained in an avalanche. It was titled “Colorado High Routes” and covered backcountry skiing in the Vail, Aspen, and Crested Butte areas. It was well-received. The guidebook was the first of its kind, detailing the 10th Mountain Division Mountain Huts sprawled across the state and was the first Colorado guidebook to ever cover “real” ski mountaineering and modern “European” style ski touring, rather than nordic style skiing on low-angled terrain. But that was only the beginning.

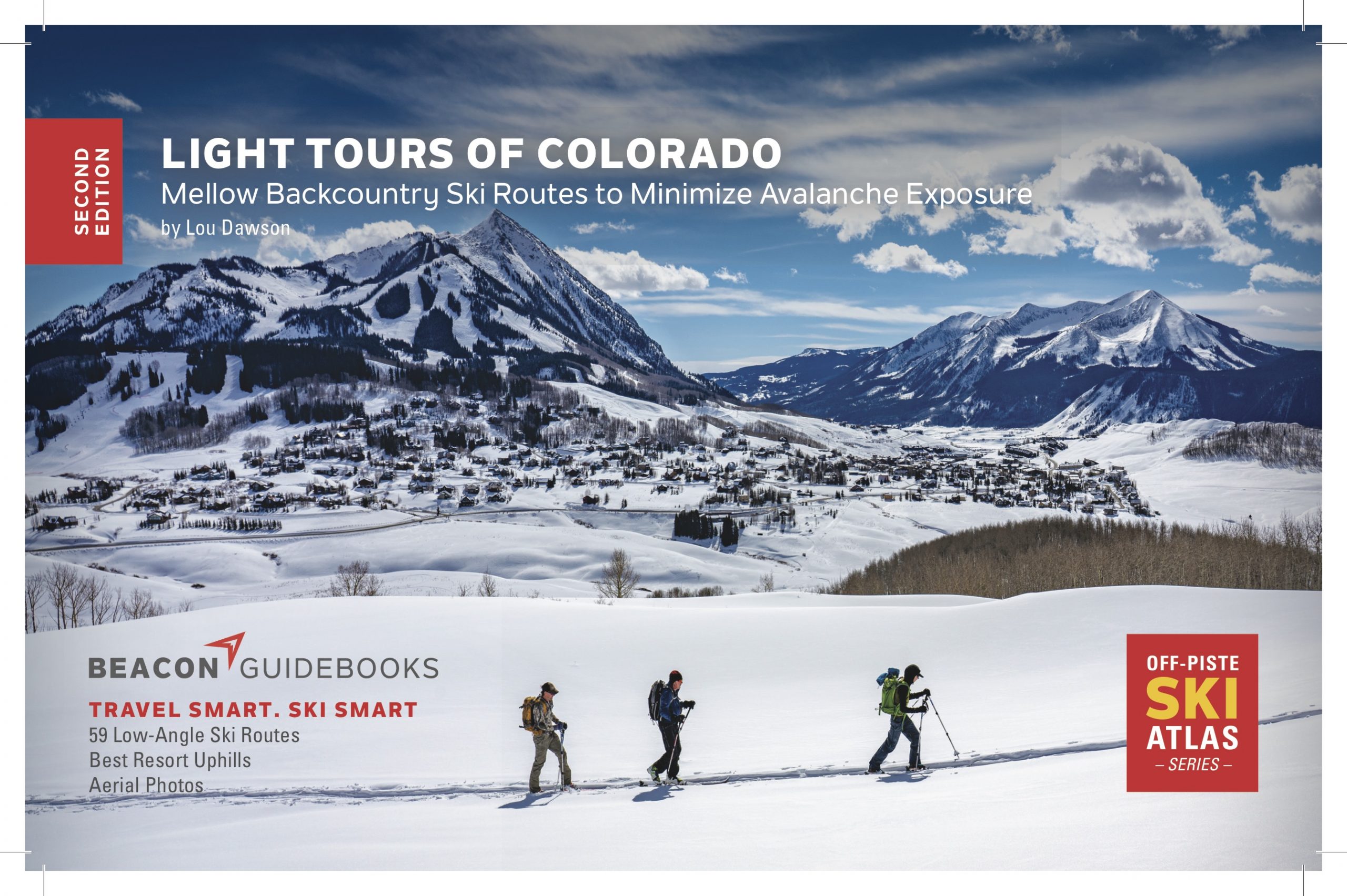

Dawson never quit writing guidebooks since his first one got published over three decades ago. He’s authored several guidebooks over the years, publishing his latest guidebook “Light Tours of Colorado” with publisher Beacon Guidebooks earlier this year. He’s the so-called Godfather of backcountry skiing guidebooks.

“It’s important to have your end result in mind and to start with something you know,” Dawson told me. Guidebooks are a lengthy ordeal and are more of a marathon than a sprint, sometimes taking years to hit the bookshelf in the form of a neatly polished, published book or booklet. A lot of skiing has to happen. Planning—maps, routes, hazards, the works—is key. A ridiculous amount of time has to be spent in the terrain you plan on writing about before you can even start writing, according to Dawson. And don’t forget about the photos.

One thing that makes self-published guidebook author Matt Gunn’s latest guidebook on British Columbia’s Spearhead Traverse stand out is the quality of his photographs. It’s the third guidebook he’s written and it’s extremely visual, filled with high-quality images taken out the side of a small airplane, which Gunn orchestrated by hiring a pilot and dangling himself out of the aircraft’s flank. Aerial images with annotated ascent and descent paths paired with notes fill his tactile book.

Gunn did everything himself and the project took him over a decade to complete—writing a guidebook on top of work, having a life, having kids, and skiing consistently proves to be a lengthy, time-consuming endeavor. “I really try to have great photos,” he told me. Having strong, annotated photos saves readers the process of interpreting the written information and applying it to the terrain at hand. Nowadays, readers can have a visual image of how to approach and ski a line with GPS maps on their smartphone but back in the day, when Dawson first started making guidebooks, online GPS map-making resources like Gaia, Caltopo, and GIS didn’t exist, making the process much longer—years longer—than it takes today. But what separates a guidebook from a “follow the dots” GPS approach is that a guidebook will actually help with decision-making in avalanche terrain where a map alone doesn’t.

The main difference between Dawson and Gunn’s process was that Gunn made the entire book himself in PDF format and sent the ready version to a printer, whereas Dawson worked with publisher Beacon Guidebooks who organized his information, hired an editor to edit it, published it, and then marketed it. However, both Gunn and Dawson had similarities in their guidebook-writing processes that can be summed up into several key points that serve to make a solid guidebook. In a nutshell, they include:

- Knowing what exactly you want to write about—the mountain range, terrain, ski descents, etc.

- Researching the areas and studying maps, maps, maps. GIS is a great resource but takes time to learn, according to Gunn.

- Going out and actually skiing the lines—the fun part.

- Documenting the areas with extensive notes and photographs, both from the ground and the sky.

- Organizing the notes and photographs into writing—the hard part.

- Extensive fact-checking.

- Conferring with other skiers or professionals who know the area you’re writing about and getting feedback (Sometimes, authors even give out samples of their guidebooks to ski tourers, who they know frequent the area, as a form of product testing).

- Tweaking your work accordingly with that feedback.

- Producing a PDF draft of the guidebook.

- Tweaking and editing all the information again—as thoroughly as you can, as many times as you can.

- More fact-checking.

- Sending the draft to an editor (Or editing it yourself).

- Printing it.

- Selling it.

Unlike Gunn, most guidebook authors use a publisher. Andy Sovick is the owner and CEO of Beacon Guidebooks, a Gunnison, Colorado-based publishing company that specializes in guidebooks. His company has published guidebooks from popular backcountry recreation areas all over Colorado and the West, like Buffalo Pass in Colorado, Snoqualmie Pass in Washington, Loveland and Berthoud Passes in the Front Range, and so forth.

“Organization is the key to freedom,” Sovick told me. His business works by essentially getting information from an author and then organizing it in an easy-to-read, accurate guidebook with topographic maps and lots and lots of photos. He has to make sure that all the maps provided by the author are up-to-date and exact, and that their information is true and easily understood. Fact-checking is the longest part of the whole guidebook-making process and requires maximum patience, according to Sovick.

Once all of the facts are checked and double-checked, and the photos and maps are organized and annotated, it’s time to arrange the book into a finished product and print it. Printing is the most costly aspect of making a guidebook. Once Sovick has a finished product, he sends a final PDF file to a printer, they print it and send him back the product, and then Sovick gets tasked with putting the book out on the shelves and turning a profit—with the author getting a share of said profit. This is often easier said than done. But most of Sovick’s published guidebooks have garnered positive responses in the mountain town shops, libraries, cafes, and other small businesses where they are sold, on top of the online marketplace. Beacon Guidebooks also put its products up for sale in a digital, PDF format that can be accessed and read via the Rakkup app, which Sovick said is gaining increased popularity these days.

At the time of this writing, Beacon Guidebooks recently published Light Tours of Colorado by Lou Dawson, which provides mellow backcountry ski routes with minimal avalanche exposure for beginners or those who aren’t looking to get “steep and gnar,” as Sovick puts it. He went on to tell me how light tours guidebooks are what’s most popular in the guidebook world right now—way more than guidebooks dealing with challenging and technical avalanche terrain. Sovick said that he’s looking to publish a light tours guidebook for every skiing region in the U.S., and is calling for any and all authors who are interested in publishing such guidebooks to contact his company.

So, it all starts with an idea—a vision. From there it takes time, skiing, and work—lots of it. The top two resources you can have when endeavoring to write a backcountry guidebook are “time and good touring partners,” Gunn says. It also takes skilled photography, analytical thinking, detailed note-taking, talking with experts, scrutinous fact-checking, attention to detail, patience, and above all, a love for the mountains.

Dawson’s a self promoting gaper from New Jersey. Why is it that every ‘guide book’ seems to be written by some transplant hell bent on ruining other peoples home area. Weather it’s with a ski guide book, or a fishing, or a hiking guide book. Why can’t easterners and flatlanders comprehend, you don’t give up your secret spots, you don’t tell the world where your secret fishing hole is, you don’t crap in your own backyard. Figure it out for yourself. Look what’s happened to every American mountain town, article after article about these towns being ruined. Thanks guide book mentality.