On New Year’s Eve last season, I watched my uncle break his femur right in front of me on Alta’s High Rustler, a steep, double-black diamond slope not very far from the base of the Utah ski area. I’m glad it was only a femur because when I saw him slam on the cat track in front of me after helplessly watching him violently tumble 1,000 feet at a not-ok speed, I thought I had literally watched his head explode before my very eyes. I stared, mouth agape, as his limp body rag-dolled a few more yards past the cat track before I unfroze and skied over to him, not knowing if he was still alive.

I didn’t know what to say or do once I got there but somehow managed to let the words “Call ski patrol!” escape and be heard by the nearest bystander, who was already dialing their number. Within moments a team of patrollers was there and I watched them perform a scene size up, making sure they were safe to enter the area, then run through the ‘ABCs’ of their medical training before taking my uncle away in a litter, a portable stretcher that’s easy to operate in a mountain environment such as Alta. Little did I know that this was all something I would later learn about in a Wilderness First Responder course.

Patrol gently skied my uncle away to the medical clinic at the base and as the smoke cleared and the New Year’s Eve fireworks show began popping off in the mountain twilight, I was left with a burning question I already knew the answer to. What would I do if there were no ski patrol in this situation? The answer is ‘not much’, other than call 911.

I try to spend most of my time in the mountains, which, with working a remote position at this point of my life, in my late 20s with plenty of time and energy to expend, equates to a large portion of my waking life spent outside in a remote, wilderness setting. This is great since I love the outdoors and skiing is one of my biggest passions. Still, it’s also a numbers game, meaning that the more time I spend outside in a natural environment that has inherent risks such as slipping, falling, triggering avalanches or rockfall, becoming hypothermic, or a long list of other potentially life-threatening situations, the higher the probability becomes that I will eventually become involved in one of these situations, whether it be my own or someone else’s. Sure, I might do my best to avoid accidents; but I can’t prevent stumbling upon one, especially in an outdoor place as busy as the Wasatch, nestled right next to Salt Lake City, a town of over a million people. What if I did encounter a situation like with my uncle but it was way out in the bush, hours away from a road, and maybe without cell signal, too? This possibility was becoming one I could no longer willingly ignore.

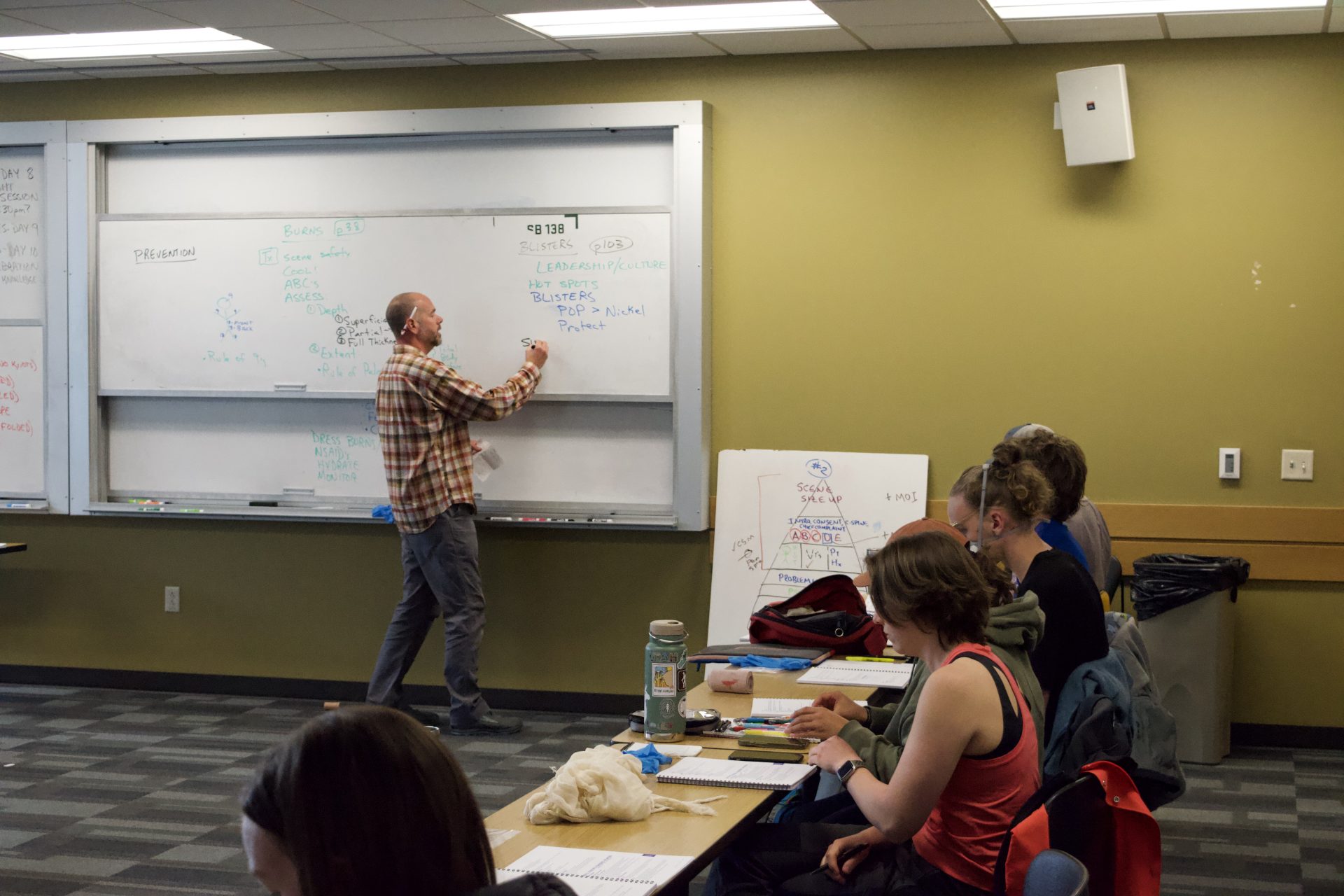

So I enrolled in a NOLS Wilderness First Responder (WFR) course, which I took in person, in Utah in May. It was a game-changer. I learned so much, with the course properly equipping me with essential skills and knowledge for handling medical emergencies in remote environments. I feel much more competent being out in the wilderness and like I can ‘not die’ when being out there, which is the first and most important thing after having fun—to make it home safely.

These are some key takeaways from the course that have significantly enhanced my preparedness and confidence in the wilderness:

1. Comprehensive Emergency Response: The course provided thorough training on assessing and managing a wide range of injuries and illnesses that can occur in the wilderness. From broken bones and sprains to hypothermia and heatstroke, I learned how to stabilize patients and provide critical care when professional medical help is hours or even days away.

2. Effective Patient Assessment: One of the most valuable skills I acquired is the ability to conduct a systematic patient assessment. This involves quickly evaluating the scene for safety, performing a primary survey to identify life-threatening conditions, and conducting a secondary survey to gather detailed information about the patient’s condition. This structured approach ensures that no critical aspect of the patient’s health is overlooked.

3. Improvised First Aid Techniques: In the wilderness, medical supplies can be limited, so improvisation is key. The course taught me how to use available resources to create splints, bandages, and other medical aids. For example, using clothing and sticks to stabilize a fracture or creating a makeshift litter to transport an injured person. These skills are crucial for effective wilderness first aid.

4. Leadership and Decision-Making: Wilderness emergencies often require quick thinking and decisive action. The WFR course emphasized the importance of leadership in crisis situations, teaching me how to prioritize tasks, delegate responsibilities, and make informed decisions under pressure. This training is invaluable for ensuring the safety and well-being of both the patient and the entire group.

5. CPR and AED Use: Learning how to perform CPR and use an Automated External Defibrillator (AED) is a fundamental part of the WFR curriculum. These skills are vital for responding to cardiac emergencies, which can be life-saving in remote areas where advanced medical care is not immediately available.

6. Environmental Awareness: The course also highlighted the importance of understanding the environmental factors that can impact a patient’s condition. This includes recognizing the signs and symptoms of altitude sickness, identifying poisonous plants and animals, and understanding weather-related health risks like drowning, avalanche burials, or hypothermia. This knowledge helps prevent emergencies and enhances overall safety in the wilderness.

7. Teamwork and Communication: Effective communication and teamwork are critical in wilderness settings. The WFR course provided practical exercises in which I worked with others to solve complex medical scenarios. These experiences showed me the importance of clear communication, cooperation, and trust within a team, especially when dealing with high-stress situations that you often have to deal with when things go south in the backcountry.

9. Managing Minor Injuries: The course also covered the management of minor but common injuries such as blisters, cuts, and splinters, which are the most common ailments you encounter in the wilderness. This aspect of wilderness medicine seems small but it’s a huge aspect that can make or break a trip. I learned how to properly clean and dress wounds to prevent infection, treat blisters to avoid further discomfort, and safely remove splinters. These small yet important skills ensure that minor injuries do not escalate and compromise the safety and enjoyment of outdoor adventures.

One of the highlights of the WFR course was the creative and engaging scenarios we participated in, which is something that NOLS is known for with its wilderness courses. These simulations were not only highly educational but also incredibly fun. We found ourselves immersed in realistic wilderness emergencies, which made the learning process dynamic and enjoyable. I can’t tell you what these scenarios were exactly because I don’t want to spoil the fun for those enrolling in a WFR course but know they are clever, engaging, intense, fun, and rewarding. It spices the course up from a regular classroom-type setting and makes it playful and memorable. These hands-on experiences were invaluable in helping me apply theoretical knowledge in practical settings, ensuring that I am well-prepared for real-life emergencies.

Taking a WFR course increased my competence as a backcountry ski partner and overall outdoorsy human. The rigorous training instilled in me a deeper understanding of avalanche safety, cold-weather injuries, and emergency evacuation techniques. I also learned how long it takes on average to get rescued from a winter backcountry setting, and it’s always hours. You need to be able to handle yourself in the event of an emergency out in the snow because Search and Rescue won’t get there for a long time, even if you feel like you are still seemingly close to civilization. By taking this course, my ability to assess risks and respond effectively to potential emergencies has improved, making me a more reliable and confident companion in the backcountry.

Overall, a Wilderness First Responder course has been a transformative experience, providing me with the skills and confidence to handle emergencies in remote areas. Whether I’m leading an outdoor expedition in the mountains, skiing a sick line at the resort, or simply enjoying a hike with friends, I now feel prepared to respond effectively to medical emergencies and ensure the safety of everyone involved. I can confidently say that I can do my best in the event of an emergency and increase the chances of survival for me or anyone involved—something I could not say before taking the course. I can’t recommend getting a WFR enough for anyone who spends much time in the mountains and it is something that I will look for in my partners from now on when deciding on who to do epic missions with.

One thought on “How Taking a Wilderness First Responder Course Made Me a More Valuable Ski Partner”