Report from January 11, 2022

“A blonde bitch, beautiful and vicious.” That’s how Montgomery Atwater, one of Alta’s first snow rangers and the father of avalanche research in the United States, referred to 11,045-foot-tall Mount Superior.

Looking at Mount Superior from the town of Alta at the end of the road in Utah’s Little Cottonwood Canyon, it’s the first thing that catches your eye; a big, brutally steep face on a tall peak right off the side of the highway. It looks both dangerous and beautiful.

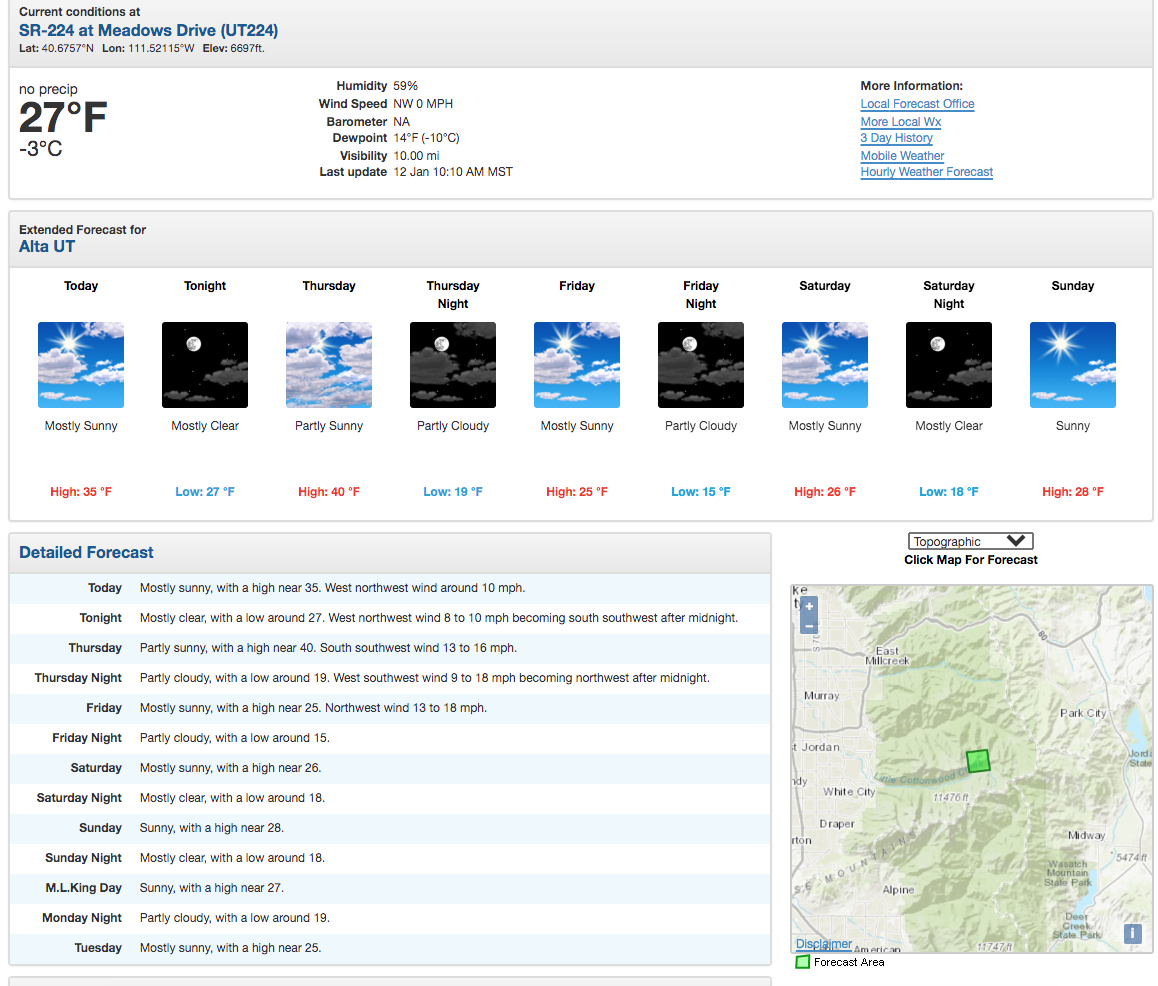

Today I set off to ski the South Face of Mount Superior—one of the 50 Classic Ski Descents of North America and a damn aesthetic line. I left Alta at 10:30 am and slogged up the hill; the skies were clear and blue, there was zero wind, and it felt unseasonably warm.

Hiking up was almost more fun than skiing down. There’s enough snow right now to tour all the way to the top of Black Knob aka ‘Little Superior.’ The skin track up felt like I was following the footprints of a forest spirit, tracking it through twisted trees and lime-green lichen painted cliffs along the knife’s edge of a forboding ridgeline. I was alone in the mountain silence.

From the top of Black Knob, it was about a 45-minute boot pack to the summit. There are a couple of sections here where you have to scramble up rocks and it feels spicy but not too much so. Then in what felt like no time at all, I found myself at the summit.

The views from the top were immaculate. I felt like I could see all of the Wasatch. I looked down and saw the little ant city where I had started way down below. I enjoyed the views for a moment and talked with a friendly local named John who chased me up there. It was his first time skiing the South Face. We were both stoked, even though we knew our south-facing line had developed a prominent sun crust over the past couple of days.

I picked a line just skier’s right of the summit that followed a miniature spine to cliffs and chutes below. Half of it was shaded and a half it was in the sun. I slashed in the shade where the snow was soft and powdery. Once I got back in the sunshine the crust layer showed itself.

The sun crust made the snow a little harder and weirder to turn in, but not as bad as I had expected. I could still ski with full confidence—it just took a little more effort on turns and the snow was fairly variable the whole run down. Most of the line was crusty and semi-soft but every dozen yards or so I’d hit lovely pockets of soft powder.

After the mini-spine line at the top, I saw some tracks running into a tight chute and followed them. The chute was steep—awfully tight—but went. I went in there and found that the snow was way icier than I had anticipated. I skied the chute cautiously, even sidestepping an ungodly technical section of ice. At one moment I questioned whether I had bit off more than I could chew and promised myself that I’d sharpen my edges when I got home.

After the chute, the snow got significantly better. I arced steep turns on the face, slowly floating to the right as I skied down. The further right I went the more sprinkled powder pockets I encountered and the more fun I had. I surfed into playful gullies with half-crusty, half-soft snow. The ski down felt never-ending, like I was skiing an infinite mountain.

I ended up popping out near the booter to Suicide Chute on the apron. The snow was softer here and I made long, easy turns in accomplishment. At the bottom of this immortal giant, I looked back at her and remembered that I was still in my home of Utah even though it had just felt like I skied a big alpine descent in the Swiss Alps. Humbled and happy, I hitchhiked back to my car knowing that this wouldn’t be the last time I skied the South Face.

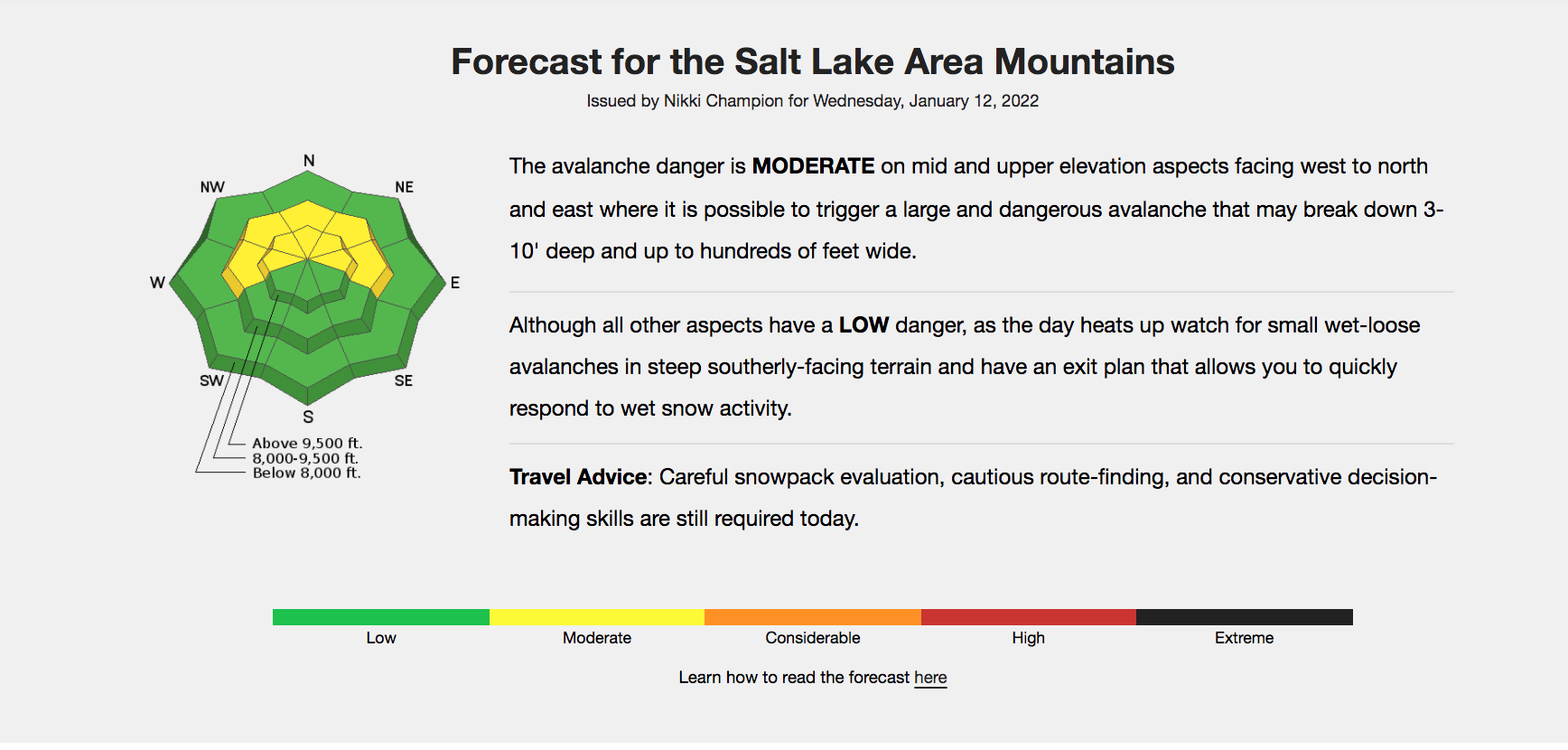

Avalanche Forecast

Weather

Photos