Marco Siffredi was not your average Joe Shralpinist, especially for his time. He was at the forefront of pushing shralpinism (alpinism with a snowboard descent) to the limits, seeking to descend some of the world’s highest peaks. Snowboarding in some of the world’s most gnarly environments is an inherently dangerous pastime, and with the amount of never-been-done descents that Marco ticked off in his life, the danger level only increased. This thirst for pushing boundaries is both what drove Marco in his pursuits, and is also likely what led him to his eventual demise in the Hornbein Couloir on Mount Everest.

Marco Siffredi was born on May 22, 1979, into a climbing family who were no strangers to the mountains. Growing up in Chamonix, France, Siffredi was quickly exposed to the joys and dangers of a mountain lifestyle. His father was a mountain guide. His brother, Pierre Siffredi, unfortunately, passed away in an avalanche in Chamonix. However, despite the pain of losing his brother, Marco grew up to be quite the mountaineer at a young age and set his sights on first descents.

Siffredi started out bagging first descents on his snowboard in 1996 in Chamonix. This was astonishingly just one year after learning to snowboard, although he had been a skier previously. The following year, he rode Aiguille du Midi, and Chardonnet. In 1998, he made a descent on Tocllaraju in Peru, accompanied by René Robert and Philippe Forte. After making the second-ever descent on the Nant-Blanc face of the Aiguille Verte in 1999 (first snowboard descent, following a ski descent by Jean-Marc Boivin 10 years previous), Siffredi began to set his sights on the Himalayas. That same season he managed to bag a snowboard descent Dorje Lhakpa, which boasts areas of 55-degree slope in which falling is not an option. This marked his first Himalayan summit, and the first time he would have a clear view of the summit of Mount Everest.

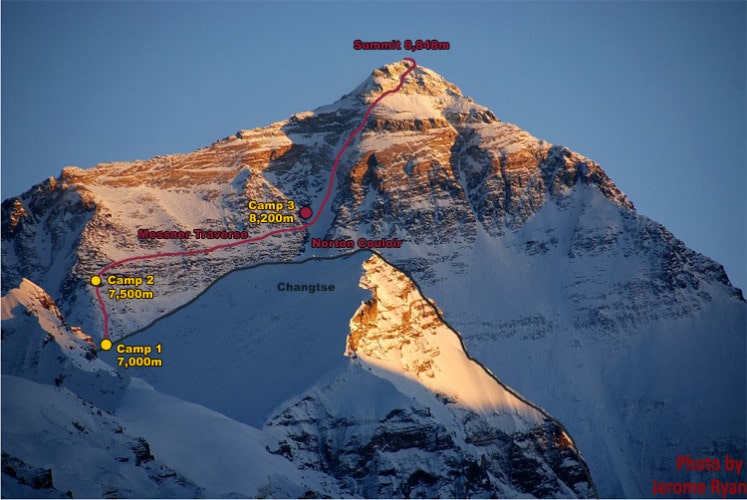

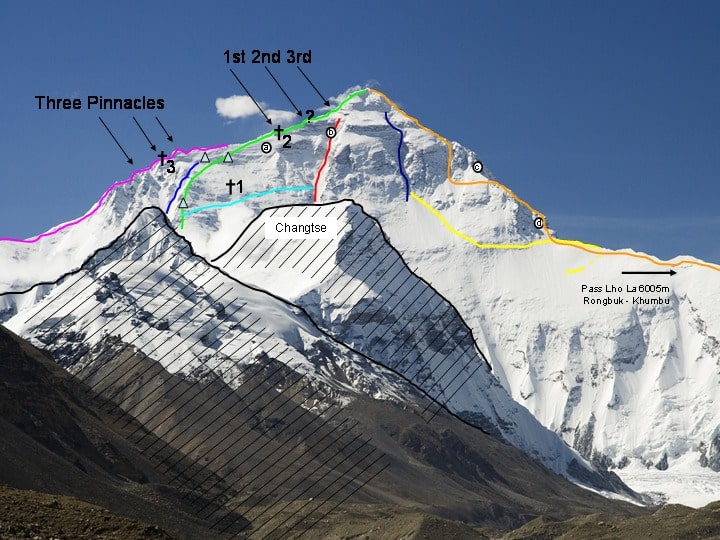

Continuing to bag peaks in the Himalayas, Marco Siffredi felt he was ready for the ultimate shralpining challenge: Mount Everest. He headed out in the spring of 2001 to peak out on Everest and descend on his snowboard via the Hornbein Couloir. Unfortunately, spring on Everest means better climbing conditions (less snow) but not a lot of opportunity for a skinny line like the Hornbein Couloir to be in. While ascending Everest, Siffredi quickly realized he would have to descend via the Norton Couloir with the Hornbein Couloir not being filled in with enough snow. After peaking out at 29,035 feet, the highest peak in the world, Siffredi shredded all the way back to Advanced Base Camp at about 20,800 feet.

It is a controversial topic whether Marco Siffredi was the first to snowboard down Everest. His descent was on May 23, 2001. Just one day before, however, Austrian mountaineer Stefan Gatt summited and snowboarded down Everest. There is a caveat to Gatt’s descent, which is what makes things messy here. Gatt encountered extremely hard-packed snow for a portion of his descent, and took his snowboard off for about 3,000 feet of the descent. Siffredi may have been a day late, but he managed to descend all the way to Advanced Base Camp without taking off his board.

Looking for a new record, Siffredi decided to head out later in the year when he would come back to take a shot at becoming the first person to descend the Hornbein Couloir via snowboard. By going later in the year, this would give Everest a chance to accumulate more snow to open up Hornbein Couloir as an option for descent. Unfortunately, the additional snow made the climbing much more difficult.

In August 2002, Siffredi set out with his snowboard to again summit Mount Everest and descend via the Hornbein Couloir. The final trek from Camp 3 to the summit takes a grueling 12-and-a-half hours, spanning three times longer than when he had bagged it in the spring of 2001. This is when things start to feel off for his crew. According to snowboarder.com, one of the Sherpas on his team, Phurba Sherpa, summited first and greeted Siffredi at the top, asking “Where are we?'” to which Marco Siffredi replied, “At the summit, but tired.” Phurba did a little dance. “Summit! Summit!” he exclaimed, but Siffredi responded with, “Tired. Tired. Too much snow. Too much climbing,” clearly not sharing the revelry.

Despite Phurba and the other two Sherpas that comprised his team warning him not to go and that he was too tired, Siffredi would not be stopped. He pushed on after resting for an hour at the summit. This would be the last time Siffredi would be definitively seen or heard from. While his Sherpas were packing up at Camp 3, they each saw what they believed to be a man standing up, and sliding silently down the mountain on the North Col, just above Advanced Base Camp. Siffredi had seemingly made it through the Hornbein Couloir if this was him. However, when they arrived at the North Col soon thereafter, they saw no evidence of tracks and assumed Marco Siffredi to be deceased.

Almost a month later, there was a memorial service held for Marco Siffredi at Everest Base Camp. Family, friends, and his girlfriend Stephanie all gathered to celebrate his life. Siffredi’s tracks could still be seen a month after his epic descent, a sign he was with them that day.

Although it is likely Marco Siffredi passed away on Everest that day, his body still has not been recovered, and no evidence of him has been found except for the tracks that could be seen leading off the summit of Mount Everest. He could have lost an edge and died of trauma, he could have been caught in an avalanche and died of asphyxiation or trauma, or he could have succumbed to the nasty weather that exists atop Everest in his vulnerable and tired condition that fateful day. Some, like Marco’s sister Shooty, speculate he may be still alive and living in secrecy in order to fully focus on pursuing new never-been-done lines. For now, Siffredi’s fate remains a mystery, but one thing is for certain. Siffredi was one gnarly dude and one of the best shralpinists to ever do it. His astonishingly quick progression, an undying commitment to the mountains, and the bravery it took to shred lines no one else had before, solidified him a place in snowboarding history for years and years to come.