Report from May 19, 2024

Mount Hood presides over the city of Portland, Oregon, from 11,249 feet— the highest point in the state. Summiting Mount Hood is a feather in the cap of any Pacific Northwest mountaineer or backcountry skier. On Sunday morning, I met two riders from Washington— Adam Pikielny and Moses Lurbur— in the Salmon River Lot of the Timberline Ski Area to try our hand at the summit.

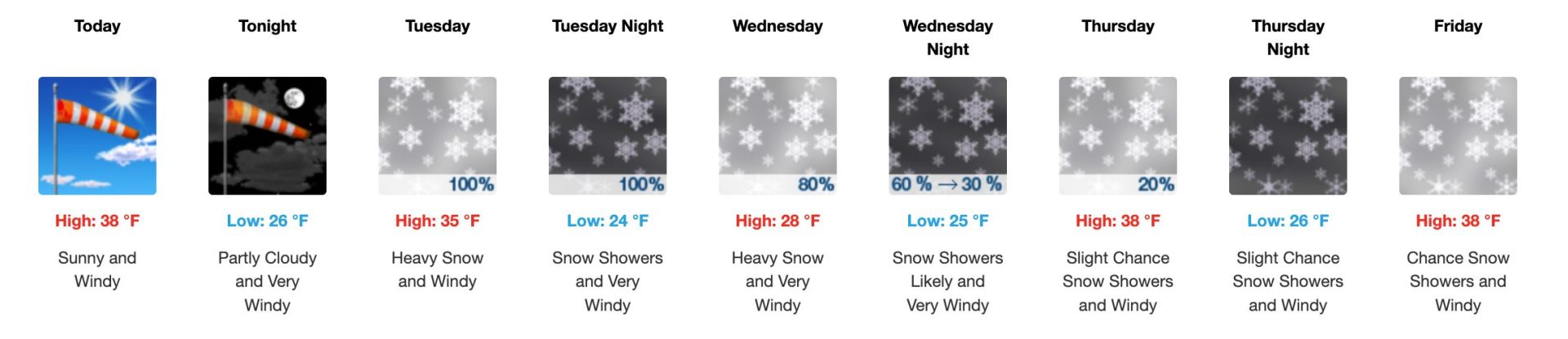

We knew we had a fairly narrow weather window. Driving through Government Camp, Oregon, at 4:30 a.m., there was widespread blowing snow and about an inch already in the trees. The parking lot was blustery with snow in the air. We also knew that another storm was due by the late afternoon.

We embarked around 5:25 a.m. and quickly realized the snow surface was very firm. Unperturbed, we made quick work of the ascent to the top of Palmer, stopping briefly to add ski (and splitboard) crampons. Then we poked out toward the Zigzag Glacier, to see if the snow conditions were a bit softer out west. And they were, occasionally— it was a mix of about 85% ice and 15% windswept snow deposit. Around 9,000 feet, we threw our planks on our backs and transitioned to boot crampons for efficient vertical travel. Notably, between the low temperatures and the biting wind, it was absolutely frigid below Crater Rock.

We arrived at the Devil’s Kitchen to discover the weather was inverted and the bowl was sunny. About the time we arrived, a U.S. Forest Service Ranger also arrived. He gave us a quick breakdown on the changing conditions over the past couple days. On his information, we were stoked to continue. Then, a group descended and told us they had turned around at the bottom of the Old Chute because they noticed shooting cracks and slabs. We were crestfallen; the news contributed to our fateful decision to scout the summit pitch without our planks.

With light loads, we scurried up and took the One O’Clock Couloir to the summit. We crossed under the traditional route to avoid the bergschrund. Instead, we crossed the Hot Rocks section, full of belching sulfur. Once we were above the clouds of billowing sulfur, we eyed the final pitch which was crowded from a couple guided groups. Fortunately, considering how cold the lower mountain was, we were in no rush. Notably, we noticed no significant signs of avalanche danger and were comforted that the weather was sufficiently cold to assuage concerns about rock/ice fall.

We arrived on a still summit around 11:30 a.m. to enjoy views of the North side, Washington, and the volcanoes beyond. As we relished our altitude, we noticed clouds beginning to gather. Familiar with Mount Hood’s inclination to gather clouds and build a cap, we opted to begin our descent. Importantly, we spent the whole descent from the summit wishing desperately that we had brought our skis— the best turns of the day would have been found above 10,000 feet.

Arriving back to our skis, we opted to ski out Zigzag, instead of testing the White River Headwall. The snow conditions were, as expected, still about 85% ice (with intermittent pockets of snow) until around 8,500 feet. It was chattery to the point where the clasps that held Adam’s splitboard together kept unlocking.

During our descent, the next storm began to arrive. By the time we reached the top of the resort, between the clouds and fresh snow falling, it was hard to see. As visibility worsened, the snow surface improved. The last couple thousand feet of turns were relatively creamy. Moses’ right heel binding was nonfunctional, so he was busy making free-heeling (on one plank) look good. Adam entertained himself with some knuckle dragging on the fresh snow and popping over of the exposed rocks. To cap off a wonderful day, we skied straight back to the car— no need for a single extra step.

Weather Forecast

Photos