APRIL 11, 2019 AVALANCHE FATALITY, RAYMOND CATARACT

By: Mount Washington Avalanche Center

Around lunchtime on Thursday, April 11, 2019, two hikers took a break on the summit of Lion Head. This ridge separates Tuckerman Ravine from a stream drainage to the north known as Raymond Cataract. While on Lion Head, they noted a skier descending into Raymond Cataract, an ephemeral, but recently popular ski descent only possible during winters with a deep snowpack.

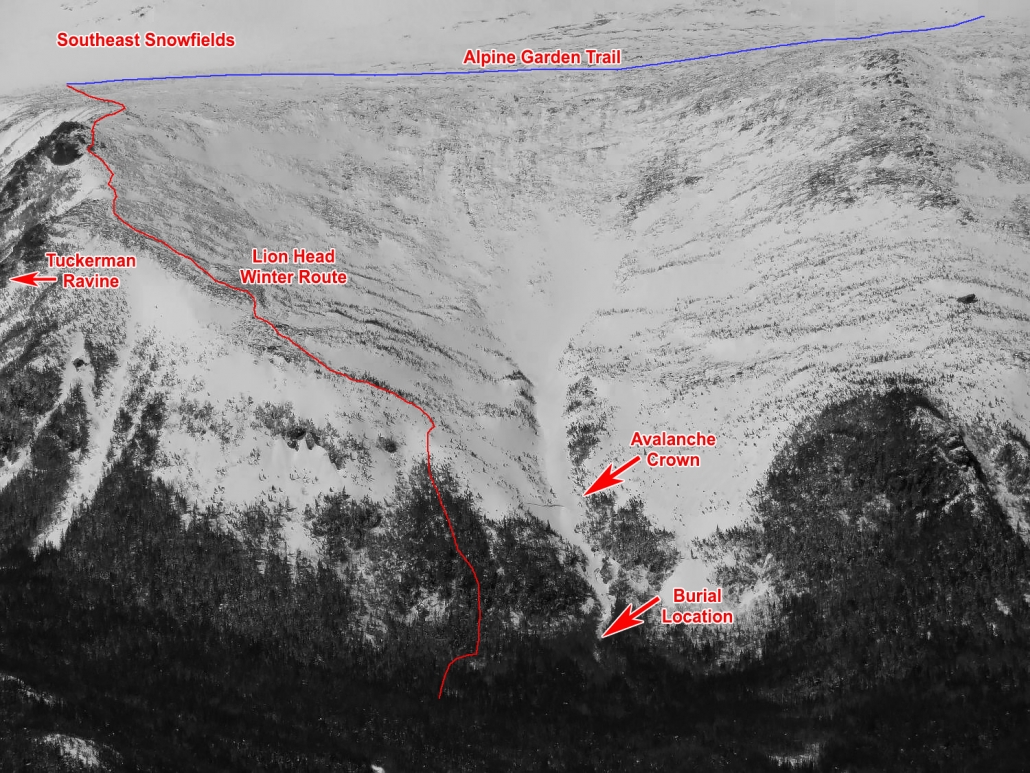

The hikers remarked on the solid and skillful turns the skier was making and watched him descend out of view. At the same time, two skiers skinning up the Tuckerman Ravine Trail watched a solo skier make a couple of turns in upper Raymond Cataract and then returned their focus to skinning. Unknown to anyone, within a few turns of both sightings, Nicholas Benedix would ski over a convex 39 degree bulge and trigger a fatal avalanche.

The crown of the avalanche was 40m wide (130’), up to 1m (3’) thick, with an average thickness of 45cm (18”). The terrain below the fan shaped bowl funneled through a 6m (20’) wide constriction. It then steepened as it became a frozen and snow covered cascading waterfall which was buried by the season’s deep snowpack. The Mount Washington Observatory webcam on top of Wildcat, aimed at the Cutler River Drainage, showed that the avalanche occurred between 1200 and 1205.

At approximately 1330, Lead Snow Ranger Frank Carus stopped to talk to a friend on the Tuckerman Ravine trail close to Hermit Lake. They discussed a new avalanche crown line that the friend had seen earlier. Due to the reported crisp, sharp edges of the crown and the possibility for human triggered avalanches that day, Carus proceeded to gear up with skis and binoculars at Hermit Lake and head back down to a viewpoint to search for clues of human involvement. The urgency of the situation increased when one set of faint ski tracks were observed on the firm snow above the crown. The time was 1353.

At 1405, after calling for the other 2 on-duty snow rangers (Jeff Fongemie and Helon Hoffer) and the Hermit Lake caretaker (Sarah Goodnow) to mobilize, Carus skinned up the Lion Head Winter Route and took a heading through the woods with an intention of intersecting the still unseen avalanche debris field in the stream bed. At 1410, Carus reached the gully near the toe of the debris. A visual search of the untracked snow below the debris confirmed that someone may have been buried. At this point, Carus hoped that they had escaped the flow somewhere above and left the area without reporting the avalanche. This is a common occurrence in the MWAC forecast area as evidenced by a small, human-triggered avalanche, with a 30cm x 15m crown (HS-AS-R2-D1-I) that likely occurred Wednesday afternoon in the Lower Snowfields of Tuckerman Ravine, which wasn’t reported.

As Carus reached the debris pile in Raymond Cataract, the slope that had avalanched was out of view. Significant hangfire remained above the fresh crown line. Carus made the decision to enter the gully without a lookout and then switched his beacon to receive. He was surprised to find a single beacon signal 24 meters away, making a mental note that the presence of one signal logically indicates a companion and another potential burial victim.

After a fine search (bracketing), Carus’ first probe attempt struck a soft, resilient object 120cm under the snow. This turned out to be the skier’s thigh. He stepped a meter or so downhill and began to dig into the slope towards the probe strike. Digging hard, he soon heard moaning from beneath the snow. More digging allowed him to find an arm and then a helmet (75cm down), as the breathing and moaning grew louder. He reassured the patient and began to ask questions to establish level of consciousness and to determine whether or not another person may have been buried. He cleared loose snow from around the patient’s face (no ice mask was observed), freed one arm, and then paused to recover from the effort to that point.

The time was 1418. Ambient air temperature was in the high 20sF with no wind and clear skies. The summit of Mount Washington temperature was recorded as 18F the previous hour with north wind at 7 mph. Debris at the scene was typical of that resulting from a firm snow slab that has reached turbulent flow, resulting in densely packed loose snow and small blocks.

Radio calls to Hoffer, acting in the Incident Commander role, were made requesting advanced life support. At 1429, LifeFlight departed Lewiston, ME, bound for a landing zone established on the leach field at the Pinkham Notch Visitor Center. Fongemie and Goodnow arrived at the scene along with two members of the public they encountered on the Lion Head Winter Route. Both Fongemie and Carus noted no additional beacon signals nor any visual clues which would have indicated multiple buried victims. Carus and Fongemie continued digging, reassured the patient, and urged him to hang on. Digging was hampered at times for various reasons; an ice block above the victim early on, the need to keep snow from collapsing along the edge of the hole, a branch near the victim’s legs, and the overall total burial depth all worked against the pair of rescuers. The victim was in an upright, seated position with his lower legs and feet buried approximately six feet down. The victim attempted to stand but his right arm was buried and his backpack was encased in snow. Carus cut away one pack strap and the victim quickly stood up. His lower legs were still buried. The snow rangers asked him to stay still and had to dodge his flailing arms as the victim struggled.

As digging continued, Carus made a primary survey for signs of trauma. Negative crepitus or deformity in spine, chest walls, pelvis, or femurs. Skin was cool and wet. The patient stood one more time and collapsed forward at about 1430. Rescuers positioned the victim’s pack under him to insulate from the snow and then worked to free his feet completely from the snow. Carus continued to assess his breathing which was labored and irregular, though clear and accompanied by moaning. Breath intervals diminished further and Carus checked for carotid pulse. Unable to get a pulse, Carus checked again, as did Fongemie. Still unable to find a carotid pulse, they checked for a radial pulse. Finding nothing, they rolled him onto his back, confirmed a clear airway, and Carus began chest compressions at 1434. Moaning continued, pupils were fixed and dilated, but good perfusion was evident in skin tone and lips. After 90 or so compressions, Carus handed off the task to Fongemie and assembled a pocket mask.

Positive ventilations were challenged by continued irregular breathing. The pair rolled him several times between chest compressions to clear fluids from his airway. Based on the coolness of his skin and continued efforts to breathe, Carus thought organ preservation that is a byproduct of hypothermia may provide a small chance for full recovery. Carus relayed this to Hoffer and lobbied for consideration of an ECMO center where blood tainted by the byproducts of metabolism can be removed, rewarmed, cleaned, and returned. Given the patient’s condition, it was clear that rapid transport to advanced medical care was needed and that continuous CPR was the only hope for recovery.

By this time, Goodnow had taken the two volunteers to the Lion Head Rescue Cache and returned with a rescue litter. CPR paused long enough to load him into the litter. To Carus, the best and perhaps only chance for recovery appeared to be rapid transport to an ECMO or at least higher medical care. Since no signs of trauma were evident and the victim was breathing, there was a chance that the lack of pulse was due to a toxic flow of blood to the heart that comes with rewarming or repositioning a deeply hypothermic patient. After sharing this rationale with the 4 others, the rescuers committed to continuous CPR by applying compressions while sliding the litter down the drainage. The streambed had open holes in the snow, rolling terrain, deep snow, and trees, so after exiting onto smoother forested terrain, Fongemie rode in the litter in order to provide better continuous compressions. Soon after, the patient was loaded into the snowcat with Fongemie and Goodnow continuing compression only CPR during the rough ride down the trail. The snowcat arrived in the Pinkham Notch parking lot at 1530 after the 2 mile trip downhill where patient care was transferred to the LifeFlight and Gorham EMS ambulance crew. Advanced Life Support measures were applied aggressively to the patient, including four shocks with a defibrillator, before the Flight Nurse declared death at 1600.

Excellent response by the 1st responders in what sounds like an absolutely trying scenario. My condolences to the surviving family and my heart goes out to the Rangers…I imagine it’s tough to lose a patient. Don’t ski alone in the backcountry, people.

This was a very well written story. Too bad the outcome wasn’t so great. Thank you.