After heating up the eastern Pacific Ocean for about a year, El Niño finally died out in May 2024. The natural climate phenomenon contributed to many months of record-high ocean temperatures, precipitation extremes in Africa, low ice cover on the Great Lakes, and severe drought in the Amazon and Central America. As of July 2024, the eastern Pacific was in a neutral phase, but the reprieve may be short-lived.

In tropical latitudes of the eastern Pacific, the ocean’s surface cools and warms cyclically in response to the strength of the trade winds—a phenomenon known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). In turn, the changing ocean disrupts atmospheric circulation in ways that intensify rainfall in some regions and bring drought to others.

In May 2023, easterly trade winds weakened and warm water from the western Pacific moved toward the western coast of the Americas, signs that an El Niño had begun, after three consecutive years of La Niña conditions. El Niño continued to strengthen into December 2023 and then faded by mid-May 2024.

“This was a sizable El Niño, but not the biggest we’ve seen in the last 30 years,” said Josh Willis, an oceanographer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Willis tracks the signature of sea level change across the globe by using satellite measurements of sea surface height. Warmer water expands, raising sea levels, while cooler water contracts, lowering them.

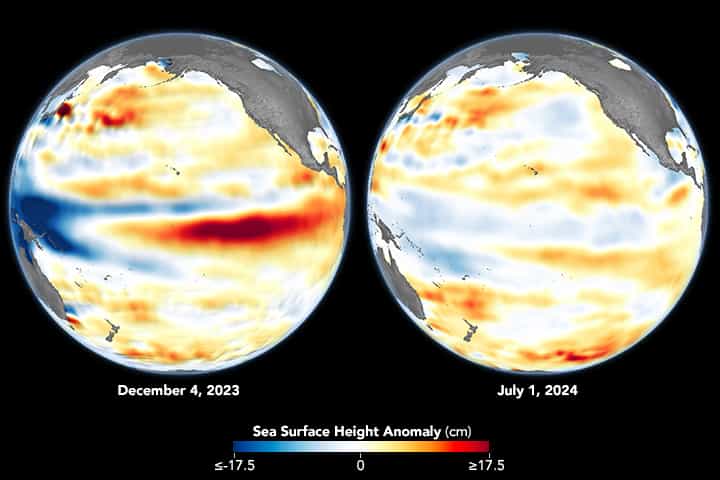

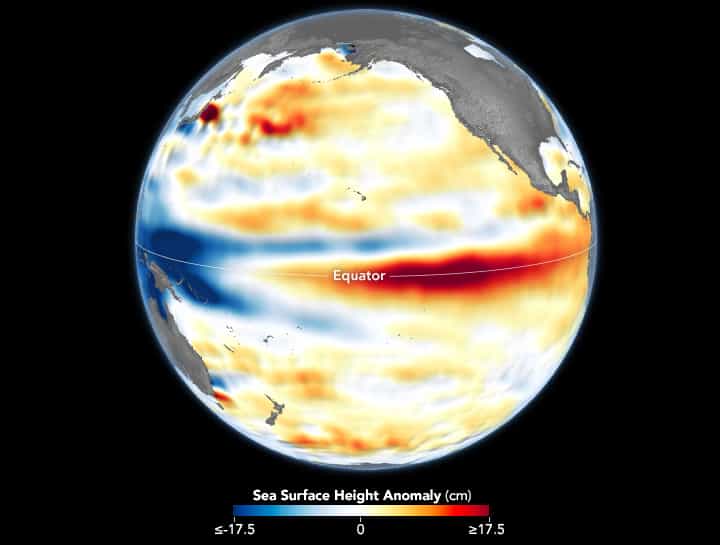

The maps above depict sea surface height anomalies across the central and eastern Pacific Ocean as observed on July 1, 2024 (right), during the neutral phase, compared to December 4, 2023 (left), near the peak of the El Niño. Shades of red indicate areas where the ocean stood higher than normal; blues indicate sea levels that were lower than average; and normal sea level conditions appear white. In a report from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, the sea surface temperatures in December for the key tropical Pacific monitoring region (from 170° to 120° West longitude) measured 2° Celsius above the 1991–2020 average.

Data for the maps were acquired by the Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich satellite and processed by Willis and colleagues at JPL. Note that signals related to seasonal cycles and long-term trends have been removed to highlight sea level anomalies associated with El Niño and other short-term natural phenomena.

Even at its peak in November and December, the intensity of the 2023 El Niño did not match that of the largest events in recent decades. During the previous record-setting events of 1997–1998 and 2015–2016, sea levels were much higher (warmer), and the high sea levels were spread over a much larger area of the central and eastern Pacific.

Even so, this moderately intense El Niño contributed to climate disturbances around the world. Precipitation patterns were disrupted in Africa: southern parts of the country suffered a dry spell that parched almost half the corn grown in Zambia, while the Horn of Africa saw devastating flooding. Severe drought in the Amazon led to huge understory fires in the northern state of Roraima. El Niño also contributed to heat stress in coral reefs, intense precipitation on the U.S. West Coast, low ice on the Great Lakes, and fires in Indonesia.

El Niño often coincides with the warmest years in the global temperature record. Warm sea surface temperatures, on top of the long-term warming trend from greenhouse gases, helped global temperatures jump enough to create a new record for heat in 2023. An analysis by scientists at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) found that May 2023 to May 2024 marked a full year of record-high monthly temperatures—an unprecedented streak. Before the consecutive 12 straight months of record temperatures, the second longest streak lasted for seven months, during the El Niño between 2015 and 2016.

In May 2024, easterly trade winds picked back up, bringing sea surface temperatures (and sea surface heights) back to normal in the eastern Pacific. NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center estimates these neutral conditions will stick around until August. They forecast that La Niña is 70 percent likely to emerge sometime between August and October and persist into the Northern Hemisphere winter.

This post first appeared on NASA Earth Observatory. NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2023) processed by the European Space Agency and further processed by Josh Willis, Severin Fournier, and Kevin Marlis/NASA/JPL-Caltech. Story by Emily Cassidy.