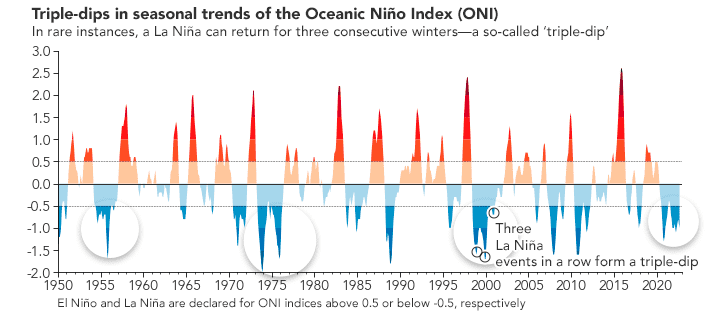

In December 2022, Earth was in the grips of La Niña—an oceanic phenomenon characterized by the presence of cooler-than-normal sea-surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific. The current La Niña, relatively weak but unusually prolonged, began in 2020 and has returned for its third consecutive northern hemisphere winter, making this a rare “triple-dip” event. Other triple-dip La Niña’s recorded since 1950 spanned the years 1998-2001, 1973-1976, and 1954-1956.

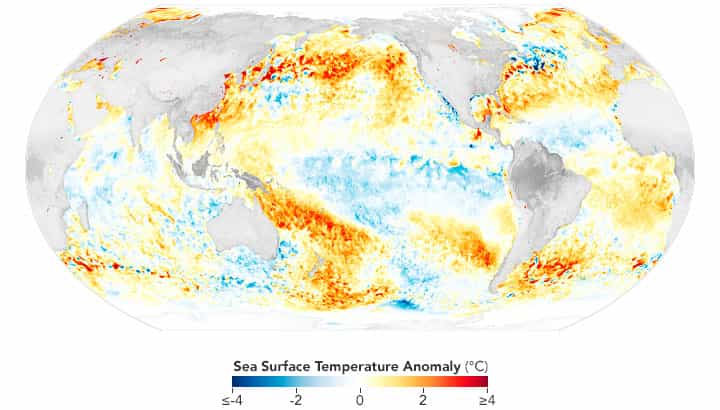

The map above shows sea surface temperature anomalies on November 29, 2022. The signature of La Niña is visible in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean as areas of cooler-than-average water. From the South American coast to the international dateline, surface waters on this day were roughly 1°C (1.8°F) cooler than usual.

Water temperature anomalies that range from -0.5°C to -0.9°C are classified as a “weak” La Niña, -1°C to -1.5°C are “moderate,” and -1.5°C and beyond are “strong.” The data are from the Multiscale Ultrahigh Resolution Sea Surface Temperature (MUR SST) project. MUR SST blends measurements of sea surface temperatures from multiple NASA, NOAA, and international satellites, as well as ship and buoy observations. (Scientists also use instruments floating within the sea to project underwater temperatures.)

“Triple-dip” La Niña events take their name from the seasonal dips that show up in charts of La Niña’s strength. Dips typically occur around December when water reaches its coolest. The Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) chart above is a three-month running mean of sea surface temperature anomalies in a patch of the topical Pacific used for monitoring La Niña (and El Niño) conditions.

Much like El Niño, La Niña events affect weather across the globe. “When the Pacific speaks, the whole world listens,” explained Josh Willis, a climate scientist and oceanographer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). “Their strongest impacts are on either side of the Pacific Ocean. Floods in northern Australia, Indonesia, and southeast Asia are common in La Niña years, as is drought in the American southwest.” Meteorologists have linked the current La Niña to a variety of natural disasters, including drought and food security problems in the Horn of Africa, flooding in Australia, and drought in the U.S. Southwest.

Part of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation cycle, La Niña appears when energized easterly trade winds intensify the upwelling of cooler water from the depths of the eastern tropical Pacific, causing a large-scale cooling of the eastern and central Pacific ocean surface near the Equator. These stronger-than-usual trade winds also push the warm equatorial surface waters westward toward Asia and Australia.

The cooling of the ocean’s surface layers during La Niña affects the atmosphere by modifying the moisture content across the Pacific. It alters global atmospheric circulation and can cause shifts in the path of mid-latitude jet streams in ways that intensify rainfall in some regions and bring drought to others.

In the western Pacific, rainfall can increase dramatically over Indonesia and Australia during La Niña. Over the central and eastern Pacific, clouds and rainfall become more sporadic, which can lead to dry conditions in southern Brazil, Argentina, and other parts of South America and wetter conditions over Central America. In North America, cooler and stormier conditions often set in across the Pacific Northwest, while weather typically becomes warmer and drier across the southern United States and northern Mexico.

La Niña tends to change in sync with the seasons. Both El Niño and La Niña tend to be at their strongest in December. “Then in the spring, the tropical Pacific resets itself and starts building toward whatever is going to happen in the following winter,” explained Willis. “The best bet right now is that this La Niña will last through the winter. Then next spring, we’ll be back in wait-and-see mode for what happens in winter 2023-2024.”

According to NOAA forecasters, there is a 76 percent chance that La Niña will persist through winter 2022-2023 (December through February) and a 57 percent chance that the Pacific will transition to neutral conditions in the spring (February–April).

This post first appeared on NASA Earth Observatory. NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data from the Multiscale Ultrahigh Resolution (MUR) project and data from the Climate Prediction Center at NOAA. Story by Adam Voiland.