Record snowfall in recent years has not been enough to offset long-term drying conditions and increasing groundwater demands in the U.S. Southwest, according to a new analysis of NASA satellite data.

Declining water levels in the Great Salt Lake and Lake Mead have been testaments to a megadrought afflicting western North America since 2000. However, surface water only accounts for a fraction of the Great Basin watershed that covers most of Nevada and large portions of California, Utah, and Oregon. Far more of the region’s water is underground. That has historically made it difficult to track droughts’ impact on the Great Basin’s overall water content.

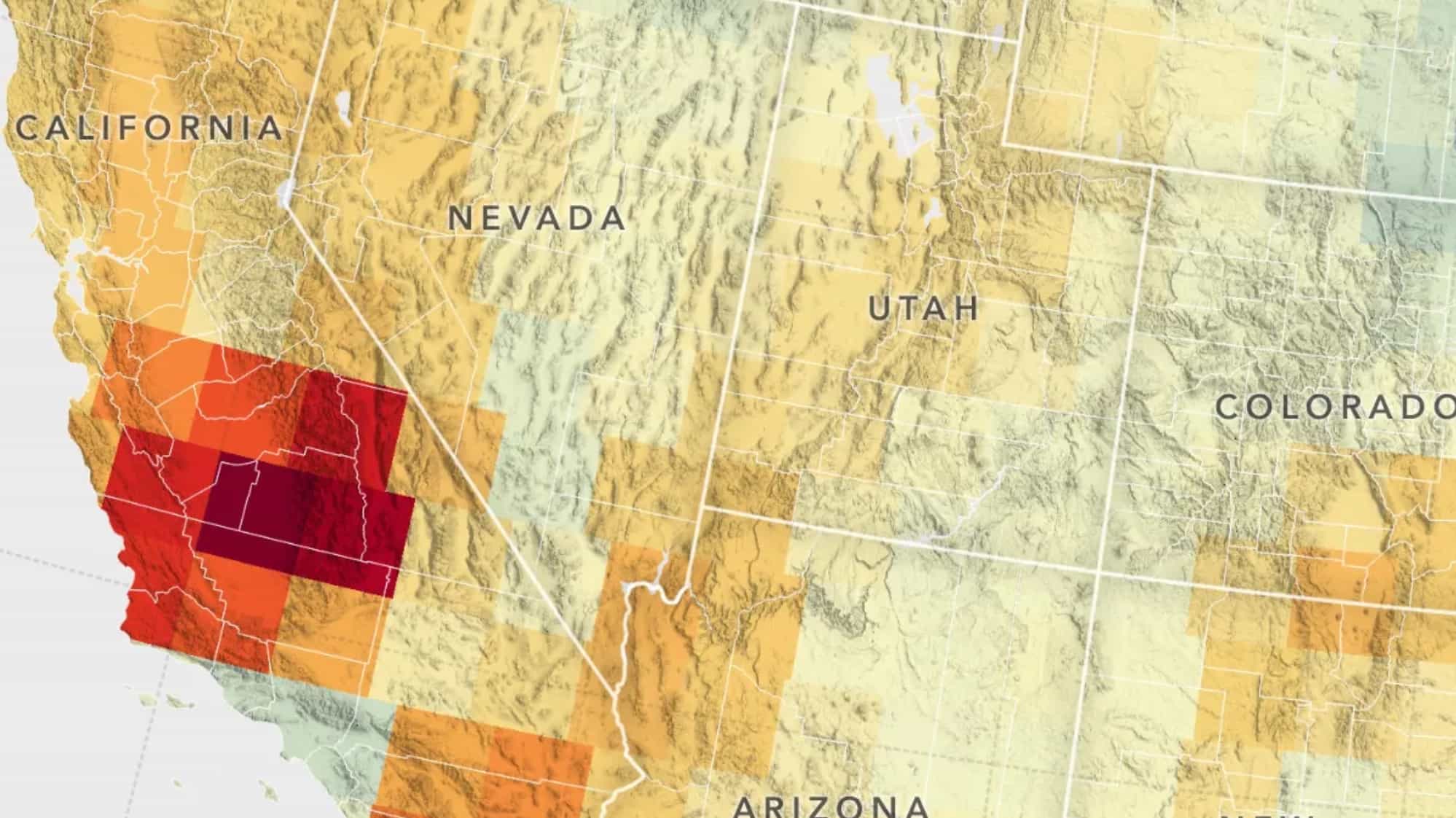

A new look at 20 years of data from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) series of satellites shows that the decline in groundwater in the Great Basin far exceeds stark surface water losses. Over the past two decades, the underground water supply in the basin has fallen by 16.5 cubic miles (68.7 cubic kilometers). That’s roughly two-thirds as much water as the entire state of California uses in a year and about six times the total volume of water left in Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, at the end of 2023.

While new maps show a seasonal rise in water each spring due to melting snow from higher elevations, University of Maryland earth scientist Dorothy Hall said occasional snowy winters are unlikely to stop the dramatic water level decline that’s been underway in the U.S. Southwest.

The finding came about as Hall and colleagues studied the contribution of annual snowmelt to Great Basin water levels. “In years like the 2022-23 winter, I expected that the record amount of snowfall would really help to replenish the groundwater supply,” Hall said. “But overall, the decline continued.” The research was published in March 2024 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

“A major reason for the decline is the upstream water diversion for agriculture and households,” Hall said. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, populations in the states that rely on Great Basin water supplies have grown by 6% to 18% since 2010. “As the population increases, so does water use.”

Runoff, increased evaporation, and water needs of plants suffering from hot, dry conditions in the region amplify the problem. “With the ongoing threat of drought,” Hall said, “farmers downstream often can’t get enough water.”

While measurements of the water table in the Great Basin—including the depths required to connect wells to depleted aquifers—have hinted at declining groundwater, data from the joint German DLR-NASA GRACE missions provide a clearer picture of the total loss of water supply in the region. The original GRACE satellites, which flew from March 2002 to October 2017, and the successor GRACE–Follow On (GRACE–FO) satellites, launched in May 2018 and are still active, track changes in Earth’s gravity due primarily to shifting water mass.

GRACE-based maps of fluctuating water levels have improved recently as the team has learned to parse more and finer details from the dataset. “Improved spatial resolution helped in this study to distinguish the location of the mass trends in the Western U.S. roughly ten times better than prior analyses,” said Bryant Loomis, who leads GRACE data analysis at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Hall said the diminishing water supplies of the U.S. Southwest could have consequences for both humans and wildlife. In addition to affecting municipal water supplies and limiting agricultural irrigation, “it exposes the lake beds, which often harbor toxic minerals from agricultural runoff, waste, and anything else that ends up in the lakes.”

In Utah, a century of industrial chemicals accumulated in the Great Salt Lake, and airborne pollutants from present-day mining and oil refinement have settled in the water. The result is a hazardous muck uncovered and dried as the lake shrinks. Dust blown from dry lake beds, in turn, exacerbates air pollution in the region. Meanwhile, shrinking lakes strain bird populations that rely on the lakes as stopovers during migration.

According to the new findings, Hall said, “The ultimate solution will have to include wiser water management.”

This article first appeared on NASA.gov and was written by James R. Riordon, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Groundwater takes years to replenish in the best of times but the aquifers are not like a bank where you can just add and remove at your convenience. Aquifers can handle minor usage and recover but the way water managers deplete the storage during dry periods can cause permanent damage. Google “subsidence” and name your local area and you will see the difference. The Central Valley in CA has areas that have subsided by well over 20′–that is 20′ of storage lost forever. The groundwater levels may return to whatever reference level the water managers want to use, but the volume of water stored will forever be significantly decreased.

I was working in the eastern Sacramento area during one drought event and saw the groundwater levels decrease between 5 and 10 feet over a large area. The groundwater levels had risen just about 2 feet when the drought was declared over. The technical folks working for the water managers had their voices squashed by the politicos and accountants who decide on water usage.