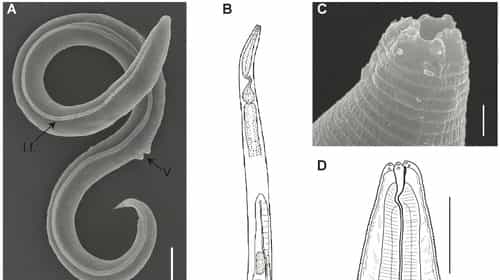

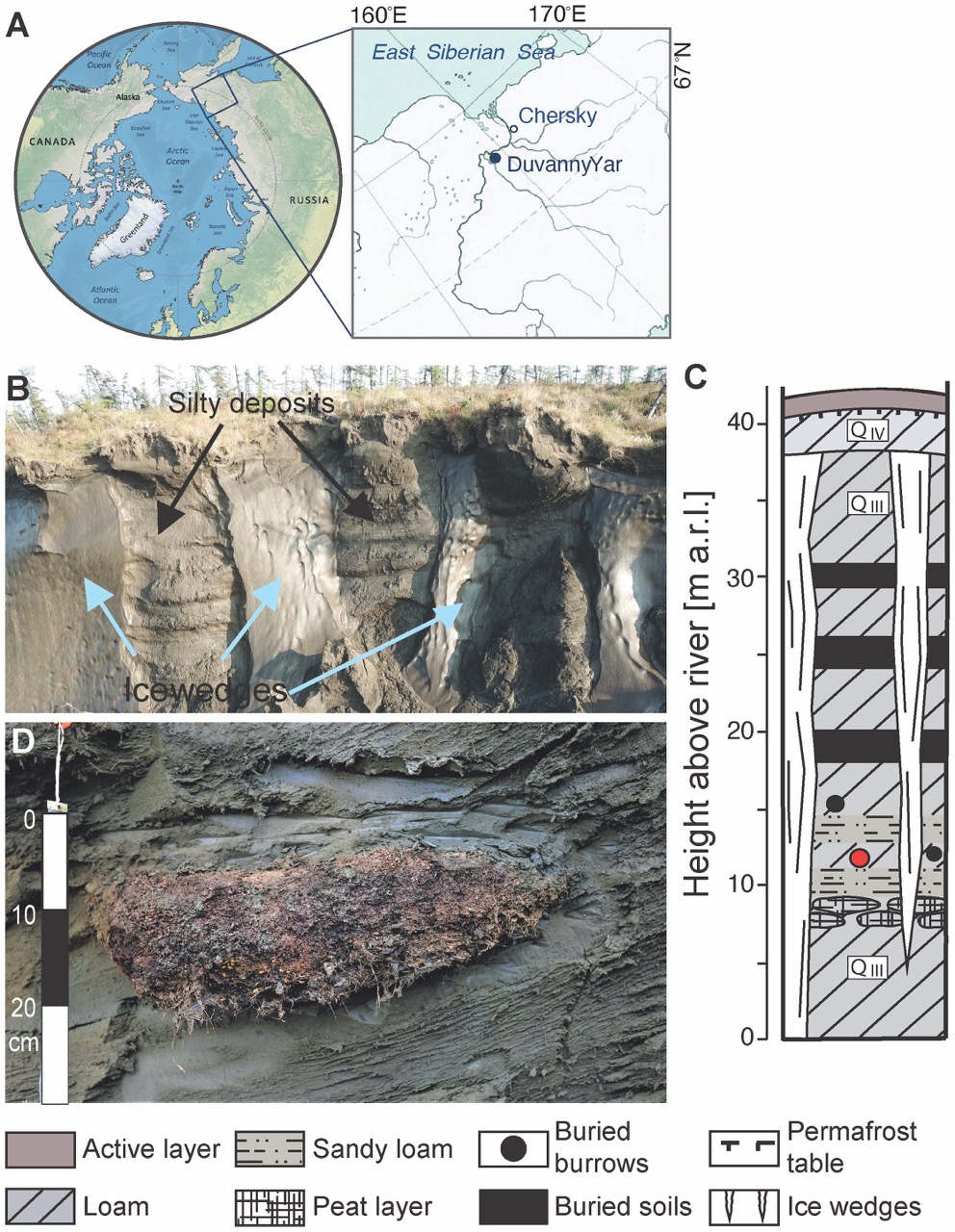

Scientists have successfully revived a 46,000-year-old nematode found in the Siberian permafrost, breaking the previous record of a few decades for a similar event. The female microscopic roundworm, a new species named Panagrolaimus kolymaensis, began reproducing after reanimation. This case highlights the phenomenon of cryptobiosis, like hitting the pause button on life (think Han Solo in the original Star Wars trilogy). When conditions get too harsh, like extreme cold, the nematode slows its body down and waits out. Then, when things get better, it can wake up and start living again. The discovery offers insights into species’ adaptive capabilities and their potential responses to environmental shifts due to climate change.

Nematodes, known for their adaptability, inhabit various environments globally. However, many species are still undiscovered. The roundworm’s endurance is remarkable, considering it lived through the Pleistocene epoch, adding a unique perspective on evolution and possibly redefining our understanding of extinction.

Awakening these organisms is relatively simple: thaw the soil gradually to avoid harm and provide bacteria for nutrition. The nematodes begin to move and reproduce. The species bred through parthenogenesis (i.e., didn’t need a mate), and more than 100 generations have been cultivated from the original specimen.

Research into these organisms could influence strategies to conserve biodiversity and mitigate climate change effects, offering a fascinating testament to life’s resilience and adaptability on Earth. Unraveling the mechanisms of desiccation tolerance and understanding the implications of prolonged survival for evolution remains a focus of ongoing research. Scientists are eager to explore the limits of an organism’s survivability and potential for resurrection.

The nematode’s revival from such an extended dormancy contributes invaluable insights into evolutionary processes, ultimately enhancing our understanding of life’s complexity and endurance. As we face escalating environmental changes, studying these organisms could be crucial in preserving biodiversity for future generations.