James Nestor’s Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art has been widely reviewed and praised for transforming lives. Released in 2019 on the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic, Breath spent eighteen weeks on the New York Times bestseller and has been translated into over thirty-five languages. Nestor previously wrote on freedivers, real-life aqua men and aqua women who go three hundred feet below the ocean’s surface on a single breath of air, in Deep: Freediving, Renegade Science, and What the Ocean Tells Us about Ourselves. In Breath, he elaborates on ancient breathing methods that can help skiers and snowboarders sharpen mental focus, harness breathing, and achieve double-digit gains in athletic performance.

The idea behind an exploration into the lost art of breathing originated for Nestor a decade ago. He was in a funk and consulted with a doctor who recommended he attend a breathing class. That first class, a Sudarshan Kriya practice, which is a rhythmic breathing technique that helps relieve stress, was the catalyst that sparked an exploration into conscious breathing techniques to improve his health and quality of life. Backed by hard science, interviews with conventional medical experts, and devoted conscious breathing practitioners, aka ‘pulmonauts,’ Nestor’s project began with self-imposed breathing experiments at Stanford University, followed by research into the breathwork of many cultures, throughout modern and ancient history.

Breath is an entertaining memoir. It is also a sports science book that can be approached as a guidebook to better health and well-being based on methods going back 5000 years. Beyond improving everyday lung capacity and function, overall health, mood, and longevity, breathing practices elaborated on by Nestor can supercharge cells and unlock unimagined physical potential. Breath makes clear that to ‘just breathe’ is, well, wrong—dangerous, even. How we breathe is vitally important for optimum performance in skiing and snowboarding, and the best way to do this is through our air-purifying nasal passages.

According to Nestor, evolution has not been kind to our jaws, teeth, and noses, at least not in industrialized societies. Our ancient ancestors were nasal breathers, with large, forward-facing jaws, expansive sinus cavities, broad mouths, and straight teeth. Modern humans, on the other hand, are the only mammals who have chins recessed behind their foreheads, slumped back jaws, shrunken sinuses, and some degree of crooked teeth. Through industrialization, the commodification of our food, and resulting passivity, we have evolved—or devolved—to make ourselves sick.

Our incapacity to breathe full breaths has resulted in a glut of modern-day ailments. By opening the door to wisdom outside of conventional medicine, scientists are discovering that certain negative impacts on our health can be reduced or reversed by changing the way we inhale and exhale. Breathing consciously in different patterns is proven to increase lung size and strength. It allows us to hack into our nervous systems, and control immune responses.

A cast of extraordinary characters, some that seem more out of an epic novel than a social science history, pepper Nestor’s writing. Early-nineteenth-century American traveler George Caitlin makes an appearance. Caitlin encountered a tribe in the Dakotas who “stood tall in stature, with luminous blue eyes, snow-white hair, and perfectly straight teeth.” From these ancient Plains people, the Mandan, Caitlin learned that breath inhaled through the mouth sapped the body of strength, deformed the face, and caused disease, and air through the nose was like distilled water.

“If I were to endeavor to bequeath to posterity the most important motto which human language can convey, it should be in these three words – SHUT-YOUR-MOUTH.” – George Caitlin

The key message in Breath can be summed up with Caitlin’s cautionary line. Like any great journalist, however, Nestor investigates his subject from every angle. His study is at times sobering. I found myself turning pages with one hand and holding my lips shut with the other. According to Nestor, the prevailing belief in conventional medicine over the past century or so was that the nose was, more or less, an ancillary organ. That belief has shifted.

Breath Experiments at Stanford

One pioneer bridging ancient wisdom with conventional medicine is Dr. Jayakar V. Nayak, chief of rhinology research at Stanford. Under the observation of Dr. Nayak, Nestor and co-pulmonaut Anders Olsson partake in the experiment that serves as the foundation of Breath. For ten days they live their lives breathing exclusively through their mouths, their nasal cavities clogged with silicone and taped shut, followed by a period of ten days breathing exclusively through their noses. While a proper scientific experiment requires a larger case study, what both men discover from this experience is life-altering.

Throughout the mouth-breathing portion of the experiment, they reported feeling progressively awful. They suffered apnea and dehydration. Nestor’s blood pressure spiked by 13 points—stage one hypertension. With nasal breathing, his blood pressure dropped, his heart rate variability increased by more than 150 percent, and his carbon dioxide levels rose about 30 percent, placing him in the medically normal zone. It took a day of oxygen filtered through his nose for noticeable improvement. From this point, he attempted to heal from whatever damage had been done to his body over a lifetime of mouth-breathing, collecting, and putting into practice several thousand years of teachings.

“The nose is a silent warrior, the gatekeeper to our bodies, pharmacists to our minds, and weather vane to our emotions.” – James Nestor

Confessions of a Mouth-Breather

The nose knows. Working together, different areas of the nostrils heat, cleanse, slow, and pressurize air so the lungs can extract more oxygen with each breath, up to twenty percent more than when inhaled through the mouth. Breath taken in through the nose, Nestor explains, can trigger hormones and chemicals that lower blood pressure, ease digestion, and regulate heart rate. As a mouth-breather myself, this made immediate sense to me. I have had two invasive nasal surgeries to try and improve my breathing and think about how to breathe better often, especially as a snowboarder in middle age.

What helped me wasn’t the surgical removal of cartilage from my nasal passages in my teens. I have done some kind of endurance sport most of my life, and this has developed my lung capacity to a degree, but what radically changed my health and how I experienced my sport, physically and mentally, was pranayama breathing. In the 90s, I started a regular yoga practice. I also went through a period where progression in snowboarding eluded me and it stopped being fun. I had read translations of ancient texts as part of my yoga training and knew that slow, controlled, abdominal breaths quieted the mind, which could only improve my riding. Putting this into practice, I noticed immediate improvements in my posture, and speed, which I attributed to my breathing technique lifting my anxiety. Conscious breathing can lead to an all-encompassing sense of calm and quiet confidence.

I thought I’d unlocked a secret of how yoga could improve snowboarding, but athletes and their trainers have tapped into the power of conscious breathing to enhance performance for millennia. Skiers and snowboarders, pushing against boundaries of what the human body and spirit are capable of, at high elevations, often in harsh environments, are a natural audience for this book. Nestor, himself a cyclist and runner, profiles pulmonauts in Breath who have made massive gains in sport. His breathing experiment at Stanford was inspired by John Douillard, a trainer of elite athletes and an expert in ayurvedic medicine who became convinced mouth breathing was hurting his clients.

Elite Athletic Training & the Wim Hof Method

Douillard put a group of cyclists on stationary bikes and monitored their heart and breathing rates while slowly increasing resistance on their pedals. During the first part of the trial he instructed the athletes to breathe through their noses, then repeated the experiment while the athletes breathed through their mouths. He discovered that with mouth breathing as the intensity of the exercise increased the rate of breathing increased, whereas with nasal breathing the rate of breathing decreased, with one subject mouth breathing at a rate of 47 breaths per minute, and nasal breathing at a rate of 14 breaths per minute. Douillard concluded that by nasal breathing athletes could cut total exertion in half and make huge gains in endurance.

In the 1970s Phil Maffetone discovered most standardized workouts could be more injurious to the Olympians, ultramarathoners, and triathletes he was training. Why? Because everyone is different. A pioneer in training endurance sports athletes and inventor of the MAF method, Maffetone was able to personalize training to focus more on the metric of heart rates to ensure his athletes, through conscious breathing, stayed within a defined aerobic zone, burned more fat, and recovered faster. Nestor gives the reader Maffetone’s method to determine the best heart rate for exercise: subtract your age from 180; the result is the maximum your body can withstand to stay in any aerobic state.

Carl Stough was originally a choir director. In the 1940s Stough began investigating how to obtain optimal breath for singers. He applied the knowledge he gained about diaphragmatic breathing to patients with lung disease, dancers, actors, and in 1968 the United States Olympic Track and Field Team. Under Stough’s guidance, athletes learned how to apply conscious breathing techniques at the event’s high-altitude Mexico City venue, winning more medals than ever before in the team’s history.

Wim Hof is the pulmonaut most likely known to high-level endurance athletes today because of the development of what is known as the Wim Hof Method. Hof, an amateur athlete—through yoga, meditation, and conscious breathing—unearthed the ancient technique of Tummo breathing, related to Kundalini yoga, and designed to move energy throughout the body. He simplified Tummo for the masses, promoting its powers through record-breaking stunts, including running a half marathon in snow and ice above the Arctic Circle while shirtless and barefoot. He violated the rules of conventional medicine drastically and yielded results that made scientists pay attention.

Cliffnote instructions for the Wim Hof method are this: lie on your back with your head supported, relax your shoulders, chest, and legs, and breathe into the pit of your stomach; let the breath out quickly and breathe this way for thirty cycles, each breath like a wave, inflating the stomach then the chest and exhaling in the same order. At the end of thirty breaths exhale, leaving about a quarter of the air in your lungs, and hold this breath as long as possible. Once you have reached your breath-hold limit take one huge inhale and hold it for another fifteen seconds. Gently move this inhale of oxygen around the chest and shoulders, then exhale and begin the heavy breathing again, repeating the pattern for three or four rounds and adding in cold exposure, such as exposing your naked skin to snow.

This method of heavy breathing with regular cold exposure, science discovered, releases adrenaline, cortisol, and norepinephrine, on command. The burst of adrenaline releases immune cells, the spike in cortisol helps downgrade short-term inflammatory responses, and a jolt of norepinephrine directs blood to the muscles, the brain, and other areas of the body essential in stressful situations. With Tummo/the Wim Hof Method, skiers and snowboarders can control their heart rates and temperature and stimulate the sympathetic nervous system by turning on stress specifically to turn it off again.

Tummo heats the body and opens up the brain’s pharmacy. It floods the bloodstream with self-produced dopamine and serotonin, forcing it into high-stress mode one minute and extreme relaxation the next. The body becomes more adaptable and flexible and learns that physiological responses can come under our control. We learn to control our nervous system so we bend and don’t break.

Real-Life Applications for Alpine Athletes

Much of what skiers and snowboarders accomplish in the mountains begins with mindset. Huck and pray. Breathing slowly and methodically calms the nervous system. It allows the parasympathetic to do its thing before the sympathetic—the one we use for quick bursts of extreme athletic activity—kicks in. The only way I know how to keep calm and take my riding to the next level is through breath.

Bridging science and history is no easy task. With some background in yoga, I’m not a blank slate but I do feel like an amateur pulmonaut. This is what I learned: Our bodies operate most efficiently in a state of balance, between action and relaxation, the yin/yang of ancient wisdom. The body makes energy in two ways, with oxygen–aerobic respiration, and without it, anaerobic respiration, which is generated by glucose and is quicker to access but inefficient.

When we run our cells aerobically we gain something like sixteen times more energy efficiency over anaerobic. With air purifying nasal breaths that can increase by another twenty percent. How I feel while fully conscious of my breathing on my snowboard is buoyant, like flying or floating on the surface of the mountain. With controlled breathing, combined with a daily yoga practice, I can lap for hours and still have energy afterward.

Breath has its critics. Detractors call the book anecdotal, and Nestor himself—who is an investigative journalist, not a scientist or medical expert—underqualified to inform others on such a vital topic. But journalists are by their nature truthseekers, and Nestor has unearthed and shared with the world a wealth of information anyone, at any age and state of health, can apply in some way to improve their life.

There is something for every skier and snowboarder in Breath. Conscious breathing can increase overall health, physical strength, and endurance, as well as help guide us toward the ultimate goal: progression. MAF and Tummo/the Hof Method are two methods elaborated on here; there are many others. Buteyko breathing, for example, includes techniques that train the body to breathe in line with its metabolic needs. For most of us, this means breathing less, a beneficial skill in high altitude, high performance, low-oxygen alpine environments.

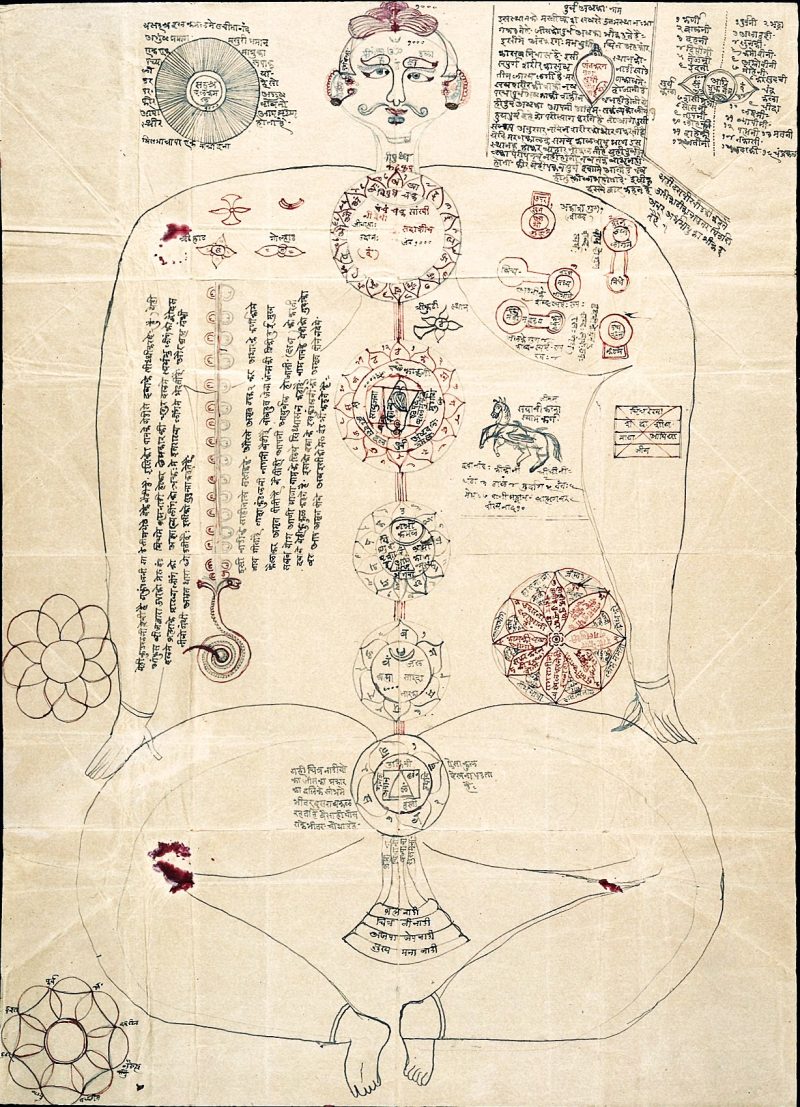

Ancient Yoga

Nestor’s work includes an appendix of the methods he discovered (and he continues to share his knowledge on his website). Lessons in conscious breathing are available from a variety of sources, and Breath is a solid entry point that can be built on over a lifetime. One takeaway is this: quiet your mind and keep your mouth closed as much and as often as you can; nasal breathing trains muscles and begets more nasal breathing (one technique involves sleeping with a small piece of tape holding your lips shut). Inhale oxygen deep into your diaphragm through your air-purifying, hormone-unlocking nasal passages, slowly releasing CO2 (to a count of 5.5). Don’t ‘just’ breathe.

Breath ends where it starts: with a lesson about ancient yoga. Yoga then is not the series of poses and life markers it is known as today. The first mention of the word ‘yoga’ in the ancient Sanskrit text Rig Veda translates as ‘breath’. Ancient yoga was conceptualized as very specific breathing methods, done seated, as a path towards accessing unimaginable mental and physical human potential and enhancing athletic performance. This was long before contemporary living and modern medicine. Conscious breathing techniques could one day be big business, as commodified as bottled water, but the stripped-down approach to achieving physiological balance through breathwork will always cost nothing; it can be done wherever, whenever, and you can take the journey as far as you’re willing to go.