A man died in an avalanche on Thursday 4th February 2021, in the East Vail Chutes, a popular backcountry area just outside the Vail Mountain, CO resort boundary. The skier left the resort through a backcountry exit gate and was in Marvin’s area when the slide occurred.

Below is the full report from the Colorado Avalanche Information Center:

Avalanche Details

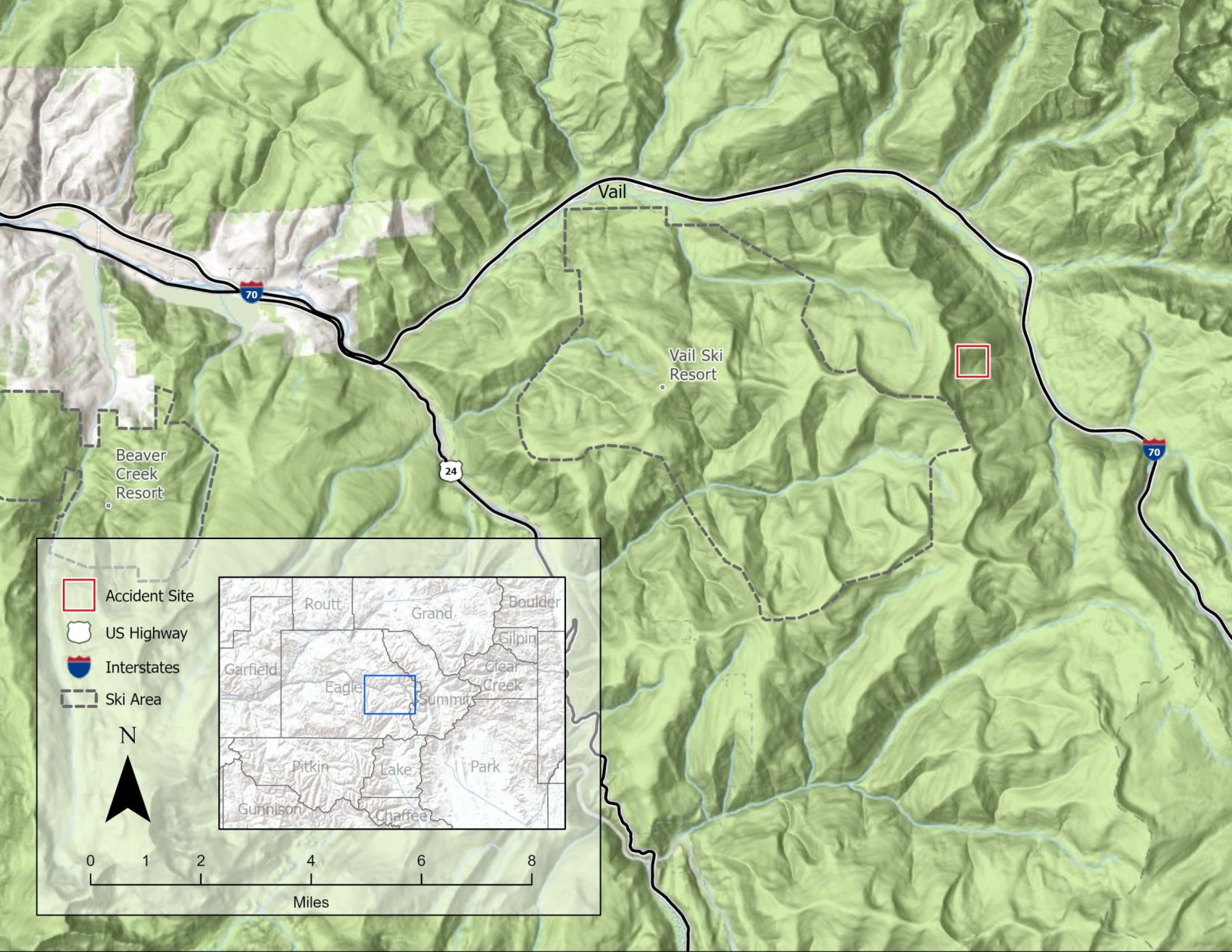

- Location: Marvin’s West, East Vail backcountry southeast of Vail

- State: Colorado

- Date: 2021/02/04

- Time: 11:10 AM (Estimated)

- Summary Description: 2 sidecountry skiers caught, 1 buried and killed

- Primary Activity: Sidecountry Rider

- Primary Travel Mode: Ski

- Location Setting: Accessed BC from Ski Area

Number

- Caught: 2

- Partially Buried, Non-Critical: 1

- Partially Buried, Critical: 0

- Fully Buried: 1

- Injured: 0

- Killed: 1

Avalanche

- Type: SS

- Trigger: AS – Skier

- Trigger (subcode): u – An unintentional release

- Size – Relative to Path: R3

- Size – Destructive Force: D2

- Sliding Surface: O – Within Old Snow

Site

- Slope Aspect: E

- Site Elevation: 11450 ft

- Slope Angle: 38 °

- Slope Characteristic: Planar Slope

Avalanche Comments

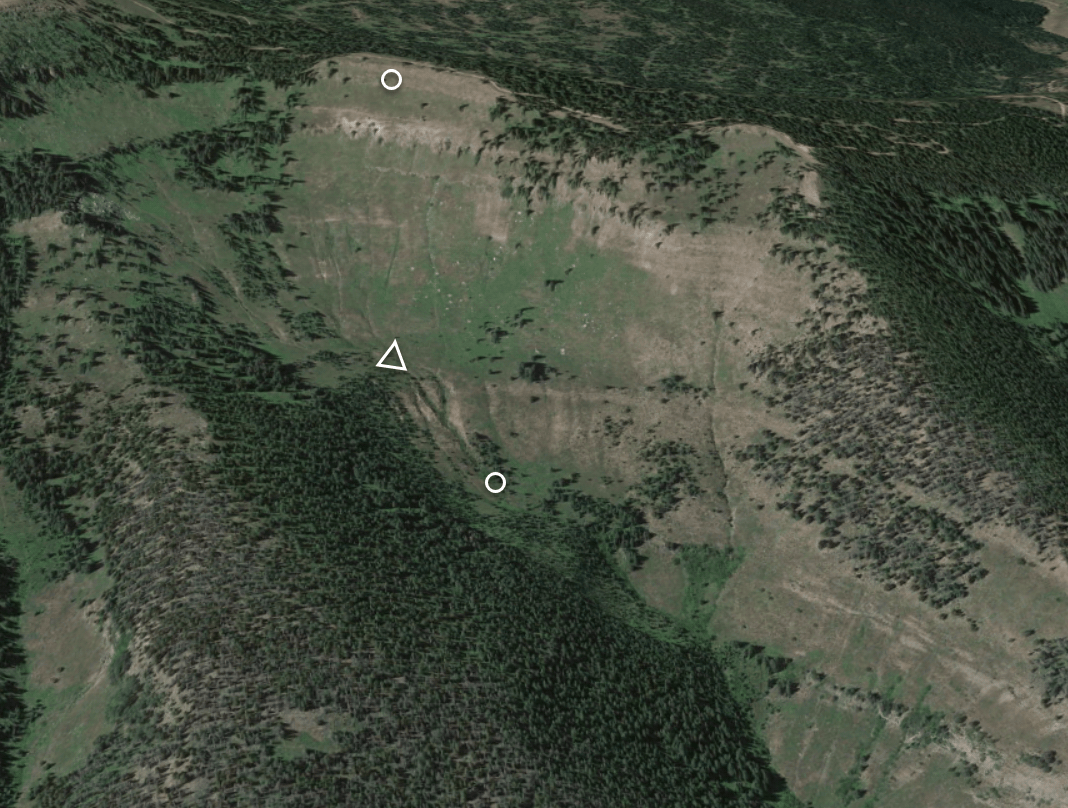

This avalanche occurred in an area locally known as Marvin’s West or Big Marvin. Marvin’s West is a steep, east-facing slope below treeline which is dissected by two cliff bands in the avalanche start zone. This was a soft slab avalanche unintentionally triggered by a skier. It was medium-size relative to the path and produced enough destructive force to bury, injure, or kill a person. It broke into old snow layers. The avalanche broke about 2 to 3 feet deep, 700 feet wide, and ran about 1000 vertical feet (SS-ASu-R3-D2-O).

Backcountry Avalanche Forecast

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC) issued an Avalanche Warning on Thursday, February 4th at 6:00 am for the next 24-hour period. The text in the Avalanche Warning read:

There is an Avalanche Warning for the Vail/Summit County, Sawatch, Aspen, and Gunnison zones. A foot or more of new snow and strong winds have combined to overload our fragile snowpack. Large, wide, and deadly avalanches will be very easy to trigger. Natural avalanches can run long distances. Backcountry travelers should stay off of, and out from underneath slopes steeper than 30 degrees.

CAIC’s forecast for Vail & Summit County on February 4th rated the avalanche danger at HIGH (Level 4 of 5) near and above treeline, and Considerable (Level 3 of 5) below treeline. Two avalanche problems were listed for the day. Persistent Slab avalanches with a likelihood of Very-Likely were highlighted on north to east to southeast aspects at all elevations, with size ranging from Large to Very-Large (up to D3). Storm Slab avalanches were the second problem, with a likelihood of Likely, size Small to Large (up to D2), on all aspects and elevations. The summary stated:

Very dangerous avalanche conditions. Avoid traveling in or around avalanche terrain today. Up to a foot of new snow from Vail to Breckenridge, down to Hoosier Pass combined with westerly winds, will overwhelm a fragile snowpack. Wind-drifted slopes facing north to east to southeast near and above treeline are the most likely places to trigger a large and deadly avalanche. Under these conditions, avalanches can fail naturally and break wider or run farther than you might expect. Sticking to low angle slopes well clear of steeper slopes above is the only way to stay safe.

Weather Summary

Extended periods of dry weather in November, December, and the first half of January created a weak base for the snowpack. On January 15, 2021, the Vail Mountain SNOTEL, which is approximately 4 miles to the west of the accident site, recorded 6.5 inches of snow water equivalent (SWE) for the winter. This was only 68% of median SWE for the thirty year reference period, 1981-2010.

From January 16 to 25, the Vail Ski Patrol measured 7.25 inches of snow with 0.65 inches of SWE at Ski Patrol Headquarters (PHQ), which is approximately 2.5 miles west of the accident site. Cold, dry weather with light winds followed through January 27. From January 30 to 31, a storm added 12 inches of snow with 1.2 inches of SWE to the snowpack, well over the forecast snow amounts. The Vail Ski Patrol recorded an additional 12 inches of snow with 0.9 inches of SWE in the 24-hour preceding the accident. Westerly to northwesterly ridgetop winds were in the upper teens and twenties, drifting the new snow to easterly-facing slopes throughout the night.

February 4, the morning of the accident, dawned cold and temperatures did not warm out of the single digits Fahrenheit for the entire day. Winds were calm out of the north. Skies were mostly cloudy with brief periods of blue sky showing through between the low clouds.

Snowpack Summary

October and November were dry months across the Northern Mountains of Colorado. At the end of November, the total snow depth measured at Patrol Headquarters at Vail Mountain was only 18 inches. The snowpack was almost entirely composed of weak faceted crystals.

A few storms in December brought the total snow height to around 30 inches by the end of the month. Periods of dry weather between storms in December kept the snowpack weak without much of a cohesive slab especially in below treeline areas where this avalanche occurred. The CAIC only recorded 11 avalanches in below treeline areas across the entire Vail and Summit County zone in the month of December. Only one of those avalanches was large enough to bury or injure a person.

The first 15 days of January were dominated by a strong blocking weather pattern across the Western US. Skies were clear, winds were calm, with no precipitation. Large diurnal temperature fluctuations created a layer of weak near-surface faceted crystals in the top of the snowpack. The CAIC continued to receive reports of avalanches during this period, but most were small, loose-snow avalanches that were not large enough to injure a person (smaller than D2 on the Destructive Scale). Few of these avalanches occurred on slopes below treeline. Harder slabs developed over the weak snow during periods of unsettled weather in the middle of January. The combination of a slab and weak facets below would result in multiple large avalanches (D2 or larger on the Destructive Scale) in the following weeks.

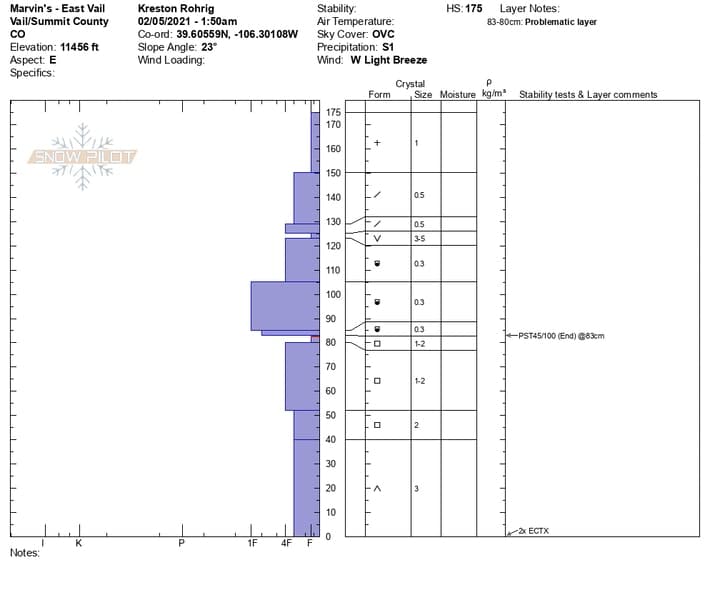

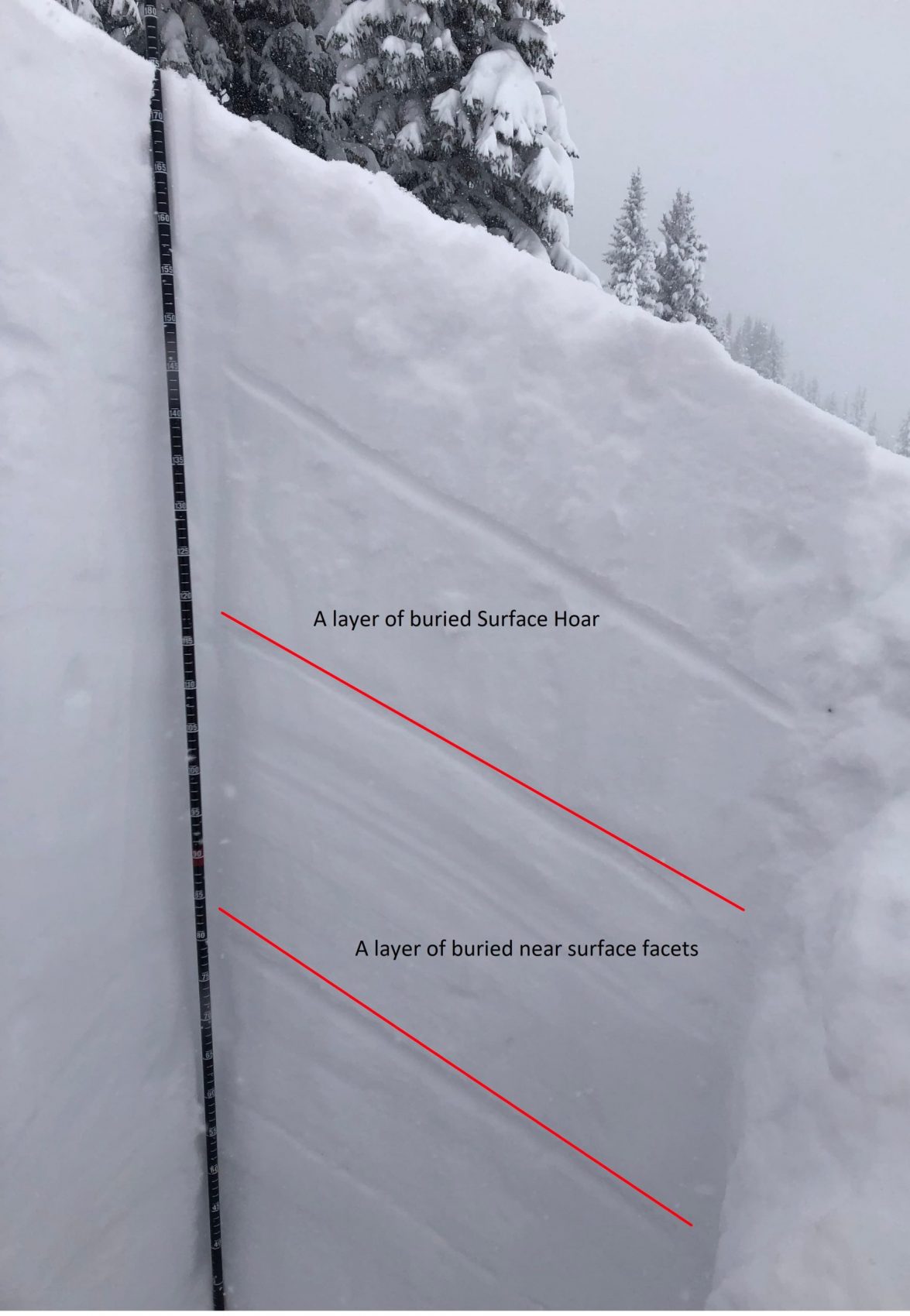

On February 5, the day after the accident, CAIC investigators observed two snow profiles above the crown face. Although another 10 inches of snow had fallen since the accident, obscuring most of the evidence from the previous day, forecasters found two weak layers in the upper snowpack. The first was a layer of small surface hoar buried about 20 inches (50 centimeters) down below the recent storm snow. The second was a layer of near-surface faceted crystal that formed in early/mid-January. This layer was buried about 40 inches (100 centimeters) deep. Neither of these two weak layers showed a high propensity for fracture propagation in snowpack stability tests (ECTX x 2, PST45/100 (End) @ 83cm).

Events Leading to the Avalanche

Skiers 1 and 2 exited the Vail ski area through a backcountry access gate around 10:15 AM. They hiked east for about 30 minutes to an area locally known as Benchmark at an elevation of approximately 11,800 feet. Then they descended along the ridgeline to the north to the top of a large open bowl locally known as Marvin’s West or Big Marvin. They arrived at the top of the bowl around 10:55 AM. Skier 1 skied down through a series of cliff bands to a bench about 800 vertical feet below the ridge and waited for Skier 2.

Accident Summary

Skier 2 began her descent. She had skied about 300 vertical feet down to a narrow opening through a cliff band when she triggered a large avalanche that broke above her. She tried to escape to the trees on the skier’s right side. She managed to stay upright and came to a stop on the apron below the cliff band buried to her knees in avalanche debris.

Rescue Summary

Skier 2 uncovered her skis and descended the debris field. She looked and saw that Skier 1 was not at their planned rendezvous point and noticed that the avalanche had run over and well past the bench where he was supposed to be waiting. She switched her transceiver to receive and began to search. She headed in the direction of the rendezvous point where Skier 1 was supposed to be waiting. Skier 2 located her partner and began digging. Skier 1 was buried 2.5 to 3 feet deep. Skier 2 cleared the snow from around Skier 1’s head and shoulders. He was not breathing. It took Skier 2 approximately 10 minutes from the time of the avalanche to uncover her partner’s head.

Skier 2 called Vail Ski Patrol at 11:20 AM to report the accident. Cellular reception was not sufficient for the ski patrol dispatcher to understand all of the call, but it was clear that there had been an avalanche accident in East Vail.

Three other sidecountry tourers (3 Riders) were riding in an area just east of Marvin’s West. They saw Skier 1 and 2 each begin their descent, but could not see the bench where Skier 1 was buried. Eventually, the three heard Skier 2 calling for help. They traversed through the trees and saw Skier 2 below. They descended the debris field to help.

The three riders helped dig Skier 1 from the avalanche debris. At 11:30 AM one of the Riders called Vail Ski Patrol dispatch. They reported that CPR was in progress, sent the dispatcher the coordinates of the accident location and confirmed that there was one victim. At 11:35 AM the ski patrol dispatcher notified Vail Police and the Eagle County Sheriff of the accident. At 11:40 AM two Vail Ski Patrollers were dispatched to the ridge above Marvin’s West to see if they could get a better idea of what was going on. The ski patrol closed the ski area’s access to the backcountry east of the ski area to make sure nobody triggered any more avalanches onto the accident site. At approximately 12:35 PM Skier 2 and the 3 Riders discontinued resuscitation efforts.

At about 1:45 PM five Vail Ski Patrollers conducted avalanche hazard mitigation for the rescue effort. About an hour later the five patrollers arrived at the burial site with a rescue toboggan. The patrollers recovered Skier 1 and transported him to authorities at Interstate 70.

Comments

All of the fatal avalanche accidents we investigate are tragic events. We do our best to describe each one to help the people involved and the community as a whole better understand them. We offer these comments in the hope that they will help people avoid future avalanche accidents.

Avalanches and avalanche involvements throughout Colorado prior to this accident demonstrated that backcountry travelers could trigger avalanches from a distance or low on a slope. Observers reported avalanches breaking wider and running further than many had seen previously.

Skiers 1 and 2 made a plan to ski Marvin’s West based on their previous experience in the terrain. Skier 1 stopped in a place he felt was safe because he had never seen an avalanche run that far before, and because that was a common rendezvous point for other people who frequent the East Vail backcountry. Travel habits developed during usual conditions do not always work during periods when avalanches are breaking wider and running further than you have previously witnessed.

Vegetation and terrain can be more reliable than recent memory to determine safer areas. You can identify safer areas by looking for the trim lines of the avalanche path. These are the areas where larger trees are still standing. You can also look for trees that are flagged. Only the downhill branches are attached to the tree and all of the uphill branches have been ripped off by successive avalanches. If you look at the area where Skier 1 was standing you will see that there are only small sparse trees. The trim lines are far away, which means that historically avalanches have overrun this area. We know this path is capable of large avalanches because in the early 1990s an avalanche ran the entire way to the valley bottom and put avalanche debris on Interstate 70.

Safe travel techniques include regrouping outside of avalanche run out zones, particularly when large avalanches are likely. In some situations that may mean leapfrogging your partner in small sections, or deciding not to ride in a specific area because there are no safe places to wait or regroup. In this particular avalanche path, there are not many safe places to stop and regroup. This is not a safe place to travel when the avalanche danger is CONSIDERABLE (Level 3 of 5).

Vail Ski Patrol contributed to this accident investigation. We greatly appreciate their assistance.

Media

Video

Images

Snowpits