On a frosty morning in Michigan’s Leelanau County, the chairlifts at Sugar Loaf Mountain hang lifeless, and the once-luxurious lodge lies in rubble. It’s a scene echoed in dozens of locations across North America. In fact, nearly 60% of all ski resorts in North America have closed since the boom of the 1960s and ’70s. Economic shifts, warming winters, and management missteps have turned many once-thriving ski areas into ghostly silhouettes on the mountainside. This investigative journey uncovers some of the most compelling of these lost resorts–why they collapsed and what, if anything, remains on their silent slopes today.

Sugar Loaf, Michigan–From Boom to Bust

At its peak in the 1970s and ’80s, Sugar Loaf was the pride of northern Michigan. The resort’s ski school taught generations of locals, hotel rooms and condos brimmed with visitors, and 3,000 to 4,000 skiers would flock to its slopes on a busy day. As the largest employer in the county, Sugar Loaf wasn’t just a ski hill–it was the economic heartbeat of the community. But underneath the happy tourists and snowpack, trouble was brewing. Years of inadequate management drove the resort into the ground by the end of the 1990s. Sugar Loaf faced several seasons of poor leadership and financial neglect before ultimately shutting down in 2000. The lights went out, the snowcats stopped grooming, and the once-booming resort was left to decay.

Locals watched in dismay as Sugar Loaf’s facilities deteriorated over two decades. Windows were shattered, roofs caved in, and vandals left neon graffiti on the walls of the abandoned lodge and indoor pool. By the time demolition crews arrived in 2021 to finally tear down the crumbling buildings, many residents had lost any nostalgia and just wanted the eyesore gone. Interestingly, the destruction of the lodge was welcomed as a relief by locals rather than a loss–a bittersweet end to a place that once brought so much life to the community. Today, all that remains is the bare, grassy ski hill and the memories of powder days that now exist only in photographs and fading recollections.

Mount Whittier, New Hampshire–When Winter Went Missing

In the White Mountains of New Hampshire, Mount Whittier Ski Area was a mid-century gem that met an early demise in 1985. In its heyday, Whittier drew crowds of New England skiers to its steep, challenging trails and its unique gondola that ferried visitors from the highway to the summit. A vintage postcard shows a packed parking lot and skiers schussing down wide-open slopes, a testament to how popular Whittier once was. But the mountain’s very features that appealed to experts–steep terrain and lack of beginner runs–proved to be its undoing. Casual skiers and families opted for gentler mountains, and Whittier’s steeps “repelled less skilled skiers” looking for an easier day on the snow.

The 1980s brought a string of warm winters, and Mount Whittier had no snowmaking system to bail it out. Without reliable snowfall, the area struggled. To make matters worse, a new interstate highway was constructed nearby, funneling would-be visitors toward larger resorts and away from tiny Whittier. A series of unfortunate events culminated in the ski area’s closure after one last sputtering season. Attempts were made in the early 2000s to reinvent the property as an adventure park with mountain biking and summer rides, but that too fizzled out. Nearly four decades later, Whittier’s lifts are rusting relics peeking out from overgrown forests, and its nostalgic trails are now reclaimed by nature. The 800-acre property was recently listed for sale–a ghost resort awaiting a visionary willing to bring this historic ski mountain back from the dead. Whether that happens or not, Whittier is a cautionary tale of a ski area defeated by warmer winters, changing markets, and a failure to adapt.

Berthoud Pass, Colorado–Powder Paradise Turned Ghost Slope

High atop the Continental Divide in Colorado, Berthoud Pass Ski Area was once a skier’s paradise that seemed blessed by the snow gods. Storms reliably buried its slopes each winter, and the area installed the state’s first double-chairlift back in the 1940s to whisk Denverites up to the powder. Berthoud Pass became legendary for deep snow and a die-hard ski culture that attracted adventurous experts and families seeking a day in the mountains. Given such perfect conditions, it’s hard to imagine this ski area ever closing. Yet Berthoud’s history was turbulent: financial woes, legal battles over permits, and ownership changes plagued the area for decades. The ski area would open and close like a stubborn snowdrift shifting in the wind–a few seasons of operation, then a bankruptcy or lawsuit would shutter it, followed by yet another hopeful revival.

By 2001, the lifts at Berthoud Pass stopped for good. Exactly why this powder paradise shut down remains a mystery–even historians scratch their heads at how a mountain with such prime snowfall could fail. One theory is that heavy investment in infrastructure saddled the small area with debt it couldn’t repay, a common downfall in the ski industry. “Gosh, why did it close? They have great snow…You see so many resorts investing so much in lift technology and not being able to pay it off,” reflected Colorado Snowsports Museum curator Dana Mathios, pondering Berthoud’s fate. Ultimately, it was likely the classic squeeze of high expenses and a short season. Running a ski area has always been a precarious business between uncertain snowfall and significant debt.

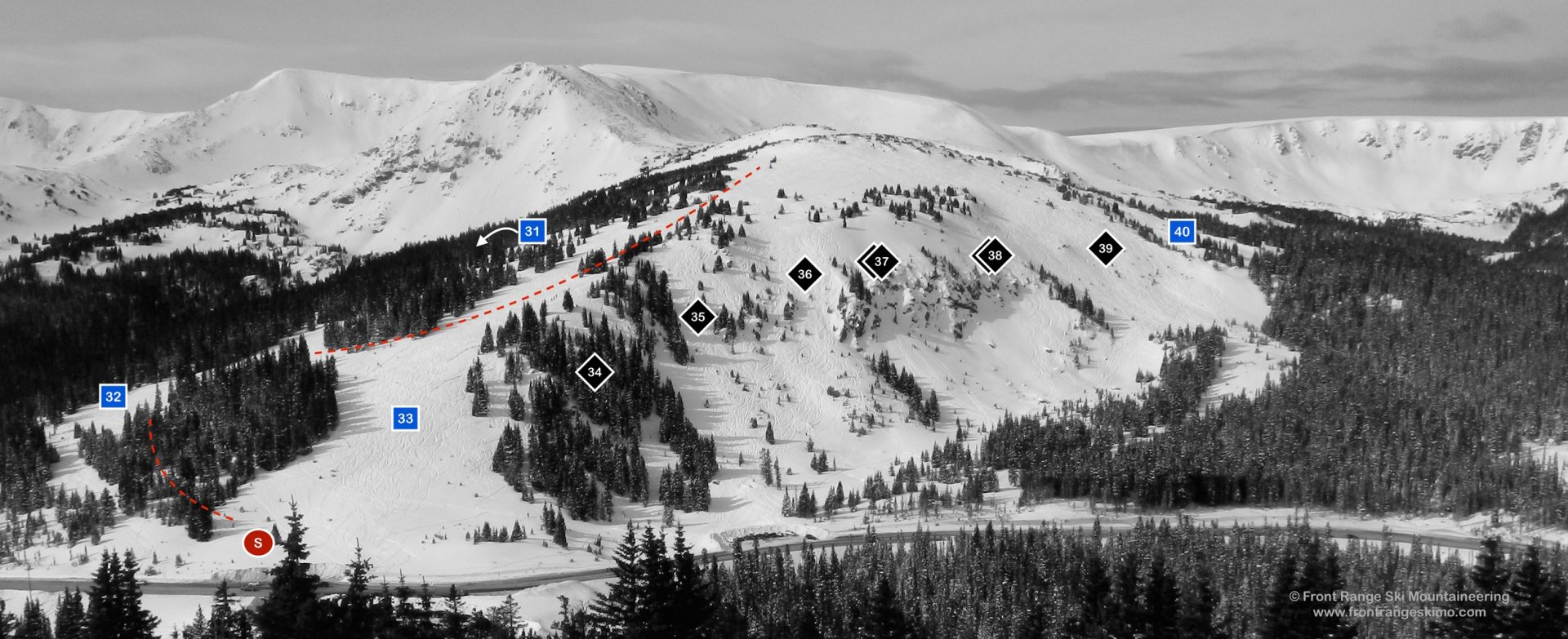

Today, Berthoud Pass is a mecca for backcountry skiers rather than a traditional resort. The old lodge and lifts are gone, but the slopes remain accessible to anyone willing to hike or skin up. On a bluebird day, it’s not uncommon to see dozens of skiers climbing these ghostly runs to carve fresh lines, keeping Berthoud’s spirit alive in a grassroots way. The mountain that once rang with the clank of chairlifts now echoes with quiet breezes–and the swoosh of skis in powder from those who remember that some ski areas don’t need running lifts to thrive in the end.

Cuchara Mountain, Colorado–Ambition and Mismanagement at 10,000 Feet

In the rugged Sangre de Cristo range of southern Colorado, Cuchara Mountain Resort is a study in boom-and-bust on repeat. This small ski area opened in 1981 with big ambitions–out-of-state investors, grand expansion plans, and an eye on becoming a destination resort. Cuchara grew fast, adding multiple chair lifts and new runs by the mid-1980s, but the growth was built on shaky finances. The initial funding from a Texas savings and loan dried up, and by 1986, Cuchara ran out of money mid-season and abruptly closed, angering skiers who held worthless season passes. It was a pattern that would repeat. A new owner reopened the mountain in 1987, only to face a winter of scant snowfall and low visitor turnout–the rookie operators didn’t have the experience (or the snow cover) to succeed. Cuchara went dark again for several years.

Hope returned in the 1990s with a succession of Texas businessmen at the helm, each vowing to make Cuchara work where others failed. For brief moments, it almost did–a massive blizzard in 1997 brought epic conditions and record attendance. But even good fortune was squandered. In one instance, the operators were caught running the chairlifts without proper state permits, a serious safety violation that forced yet another shutdown by authorities. Finally, by 2000, after yet another short-lived revival, Cuchara’s last owner closed the slopes and walked away. The U.S. Forest Service, which controls the land, terminated the resort’s permit in 2001, effectively ending any further attempts. Mismanagement, regulatory troubles, and a few lousy snow years had accomplished what no mountain could–Cuchara was left to the weeds and wildlife.

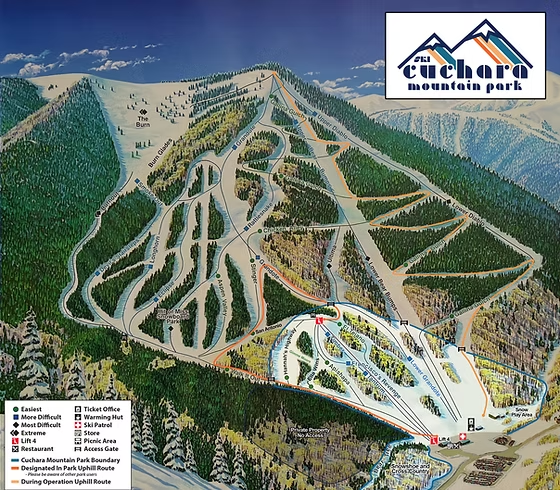

Yet Cuchara refuses to vanish entirely. Locals loved their ski hill so much that they rallied to give it a second life. Huerfano County acquired the base area in 2017 and converted it into Cuchara Mountain Park–a community-run venue for “human-powered” skiing and recreation. There are no operating chair lifts today, but backcountry skiers and snowboarders are welcome to hike up for turns, much like at Berthoud Pass. On winter days, you might see a handful of people skinning uphill, passing silent lift towers that once whirred with Texan-funded optimism. The base lodge has been repaired as a day-use shelter, preserving a piece of the resort’s past. Cuchara’s story is an alpine saga of big dreams repeatedly dashed by reality–an embodiment of how passion alone can’t overcome poor planning and patchy snowfall. Just over the New Mexico state line, its sister resort, Ski Rio, followed an almost identical arc: huge vertical and big plans undone by minimal natural snowfall, financial issues, mismanagement, and tough competition from nearby Taos. Both are reminders that Mother Nature and sound management have to ride in tandem in the ski business.

Fortress Mountain, Alberta–A Sleeping Giant of the Canadian Rockies

Not all ghost ski areas are victims of low snow or small stature–one of the most storied lies high in Canada’s Rockies, blessed with powder and big terrain. Fortress Mountain in Alberta was a beloved ski destination known for its dramatic alpine bowl and a famed curved T-bar lift. After it closed, it even starred as a backdrop in Hollywood films like Inception and The Revenant. In the late 20th century, Fortress drew crowds from Calgary and beyond, but behind the scenes, its corporate owners faltered. As newer resorts invested in fast lifts and snowmaking, Fortress’s infrastructure aged. Ultimately, failing to invest in the mountain during its final decades led to its demise. By 2006, operations ceased, and Fortress became another entry in the ledger of lost ski hills.

Unlike many ghost resorts, Fortress Mountain isn’t entirely abandoned to nature–it’s paused in time, awaiting a revival that always seems just over the horizon. In recent winters, the only skiers on Fortress’s slopes arrive via snowcat as part of a backcountry skiing operation that now uses the terrain. The chairlifts and lodges still stand, preserved in the dry, cold air, lending an eerie Mary Celeste vibe–as if the ski area might roar back to life at any moment. The current owners have long promised to rebuild and reopen Fortress as a modern ski resort and have even garnered government support to extend leases and enable development. However, a key ingredient is missing: substantial investment. Until a deep-pocketed investor arrives, Fortress Mountain remains a snow-covered ghost, proof that even a mountain with excellent snow and scenery cannot escape economic gravity.

The tales of these vanished ski areas–New England to the Rockies–reveal how fragile a ski resort can be. All it takes is a string of warm winters, a recession, an overzealous expansion, or a few bad decisions at the top, and a once-thriving mountain can go quiet. Climate change is an ever-looming threat in this mix, gradually squeezing lower-elevation hills that can’t reliably keep snow on the ground. Economic upheavals and industry consolidation have also played a role, favoring mega-resorts while mom-and-pop ski hills fight uphill for survival. And when management falters—neglecting maintenance, skimping on safety, or piling up debt—even abundant snow and loyal skiers can’t keep the lifts turning.

What remains today are ghostly reminders: a tumble of concrete where a base lodge once stood, lift towers looming quietly over regrown forests, or simply an open bowl of snow where adventurous skiers still leave tracks in homage. In some cases, communities are finding creative ways to repurpose these slopes–as parks, hiking areas, or backcountry hubs–keeping the spirit of the ski hill alive even without chairlifts. Each lost resort has its own story of rise and fall, but they all speak to the larger narrative of an ever-changing industry.

When Sugarloaf was sold to lawyer Jeff Katofsky that was the end of the resort. This guy had no intention of keeping it as a ski area. It should have been sold to local or major ski operator. Like I always say what to you call a lawyer at the bottom of the ocean, a good start. Another Michigan treasure gone. And thank you Ross Satterwhite for your actions in letting this ski area go to this douche bag.