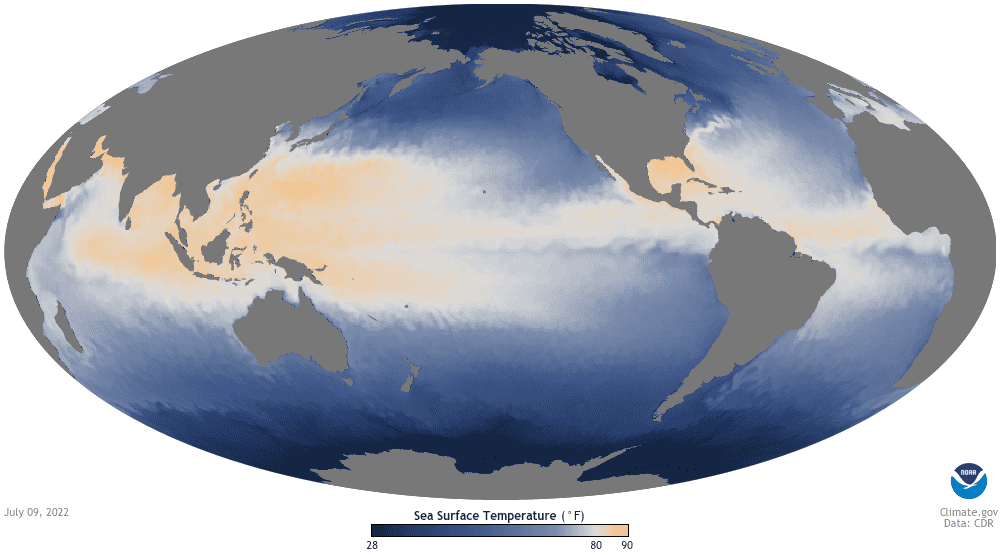

I’m in San Diego this week, gazing out across the Pacific toward La Niña’s cool tropical ocean surface. (I’m not here for Comic-Con, but there are a lot of posters around the city that keep that upcoming event in the forefront.) Just over my horizon, La Niña—the cool phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (“ENSO” for short)—remains in force, despite some warming in the sea surface temperature over the past month or so. Forecasters expect La Niña to continue through the summer and into the fall and early winter.

Ka-Pow!

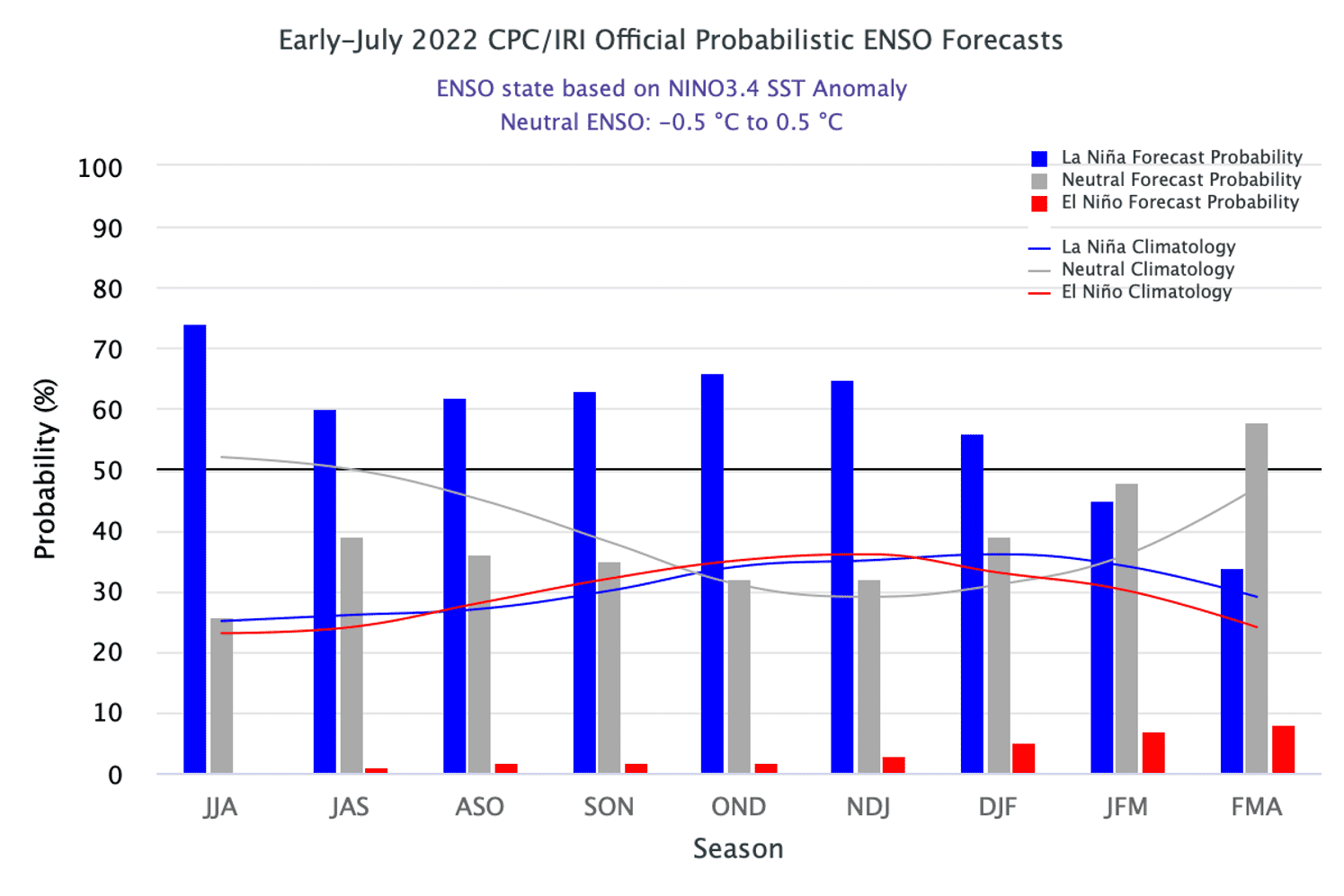

Numbers-wise, there’s about a 60% chance of La Niña through the summer, ticking up a bit to the mid 60%s around 66% by October–December 2022. The second most likely outcome is ENSO-neutral conditions. El Niño is a distant third, with chances only in the low single digits through the early winter. This forecast isn’t much different from the past couple of months.

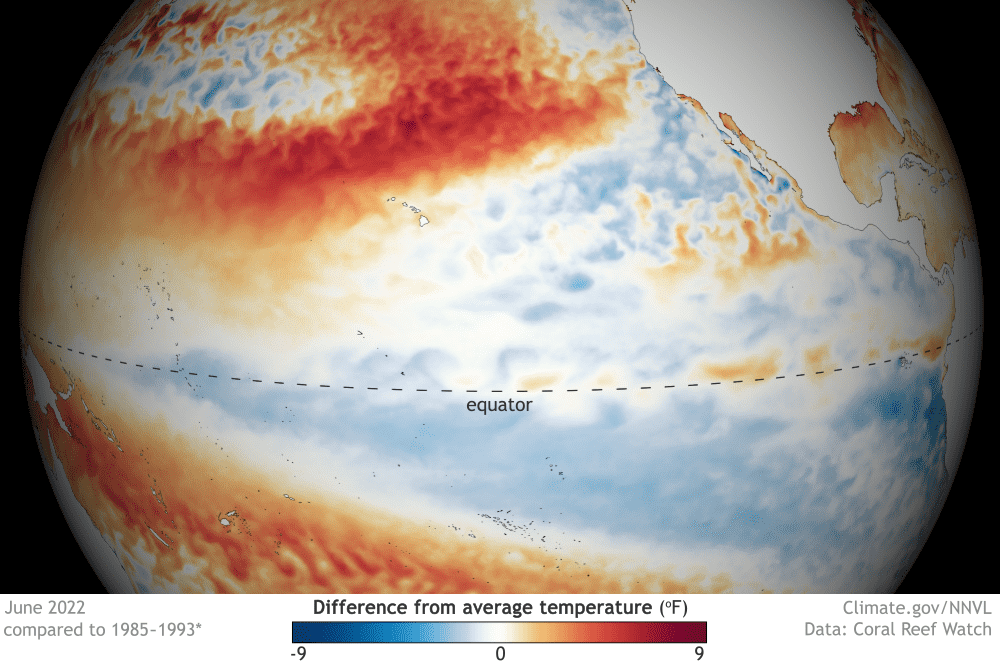

While we’re doing the numbers, let’s see how La Niña measured up last month. As I mentioned above, the cool sea surface temperature anomaly weakened a bit in June, but remained in La Niña territory. (Anomaly = difference from the long-term average, long-term being 1991–2020 here, and the La Niña threshold is -0.5 °Celsius, which is just shy of 1 degree Fahrenheit.) According to the ERSSTv5, our most consistent sea surface temperature dataset, June’s sea surface temperature anomaly in the Niño-3.4 region was -0.8 °C. This is the 7th-strongest negative June anomaly in our 1950–present record.

This recent weakening in the Niño-3.4 anomaly—it was -1.1 °C in May—is partly due to a slight diminishment of the trade winds, the prevailing east-to-west winds near the Equator, in the first half of June. When the trade winds weaken, wind-driven evaporative cooling slows and the surface warms. Also, a fairly weak downwelling Kelvin wave, a region of warmer-than-average water under the surface, has been moving from west to east over the past few months , gradually rising toward the surface.

The trade winds re-strengthened over the second half of June, and remain stronger than average as we go to press. This will likely help to cool the surface, and may contribute to an upwelling Kelvin wave, a region of cooler-than-average subsurface water that moves west to east. Along with being a sign that La Niña’s amped-up Walker circulation—the atmospheric response to La Niña’s cooler sea surface—is still present, the stronger trades are a source of confidence in the forecast for La Niña to continue through the summer.

Zowie!

That said, there may well be short-term fluctuations in the Niño-3.4-region sea surface temperature that flirt with the La Niña threshold. For example, the current weekly Niño-3.4 index is -0.5°C. (This uses a different sea surface temperature monitoring dataset, the OISST.) However, as Michelle detailed a few years ago, ENSO is a seasonal phenomenon, meaning we evaluate it using monthly and seasonal averages, not weekly. Most climate models are predicting that the three-month-average Niño-3.4 index will remain below -0.5°C, another source of confidence in the forecast.

Thwack!

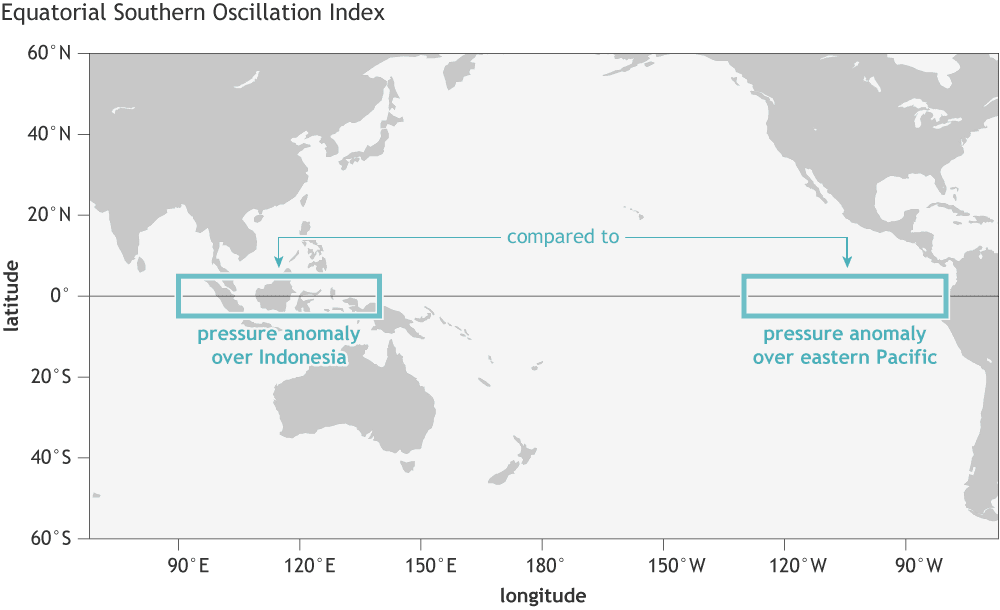

As I mentioned above, the June sea surface temperature anomaly was the 7th-most negative June anomaly on record. Where does the atmospheric response rank? Let’s take a look at the Equatorial Southern Oscillation Index (EQSOI), an index that measures the relative atmospheric surface pressure in the equatorial eastern Pacific versus that in the western Pacific.

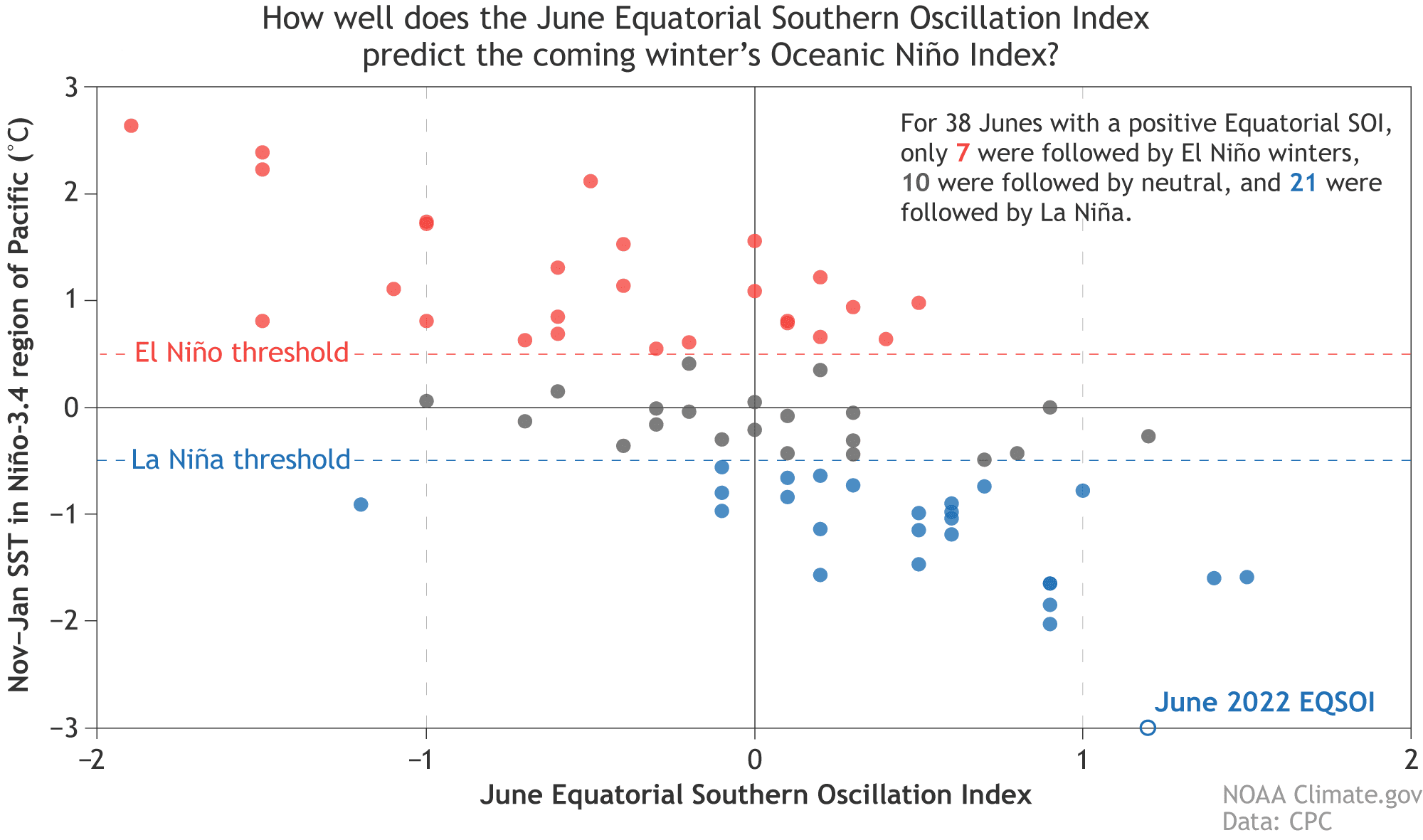

When this index is positive, it means the pressure is relatively higher in the east and lower in the west, indicating a stronger Walker circulation. June 2022 tied for third strongest on record (1950–present), which got me wondering about the relationship between the strength of the Walker circulation in the summer to the Niño-3.4 index in the following early winter.

It turns out that the June EQSOI has a correlation of about 0.7 with the Niño-3.4 index in the following November–January period. This is a fairly strong correlation, but by no means does it guarantee any particular November-January outcome. The other tied-for-third June, 2013, was followed by an ENSO-neutral winter. Most other Junes in the range of the 2022 value were followed by La Niña winters, though.

Blammo!

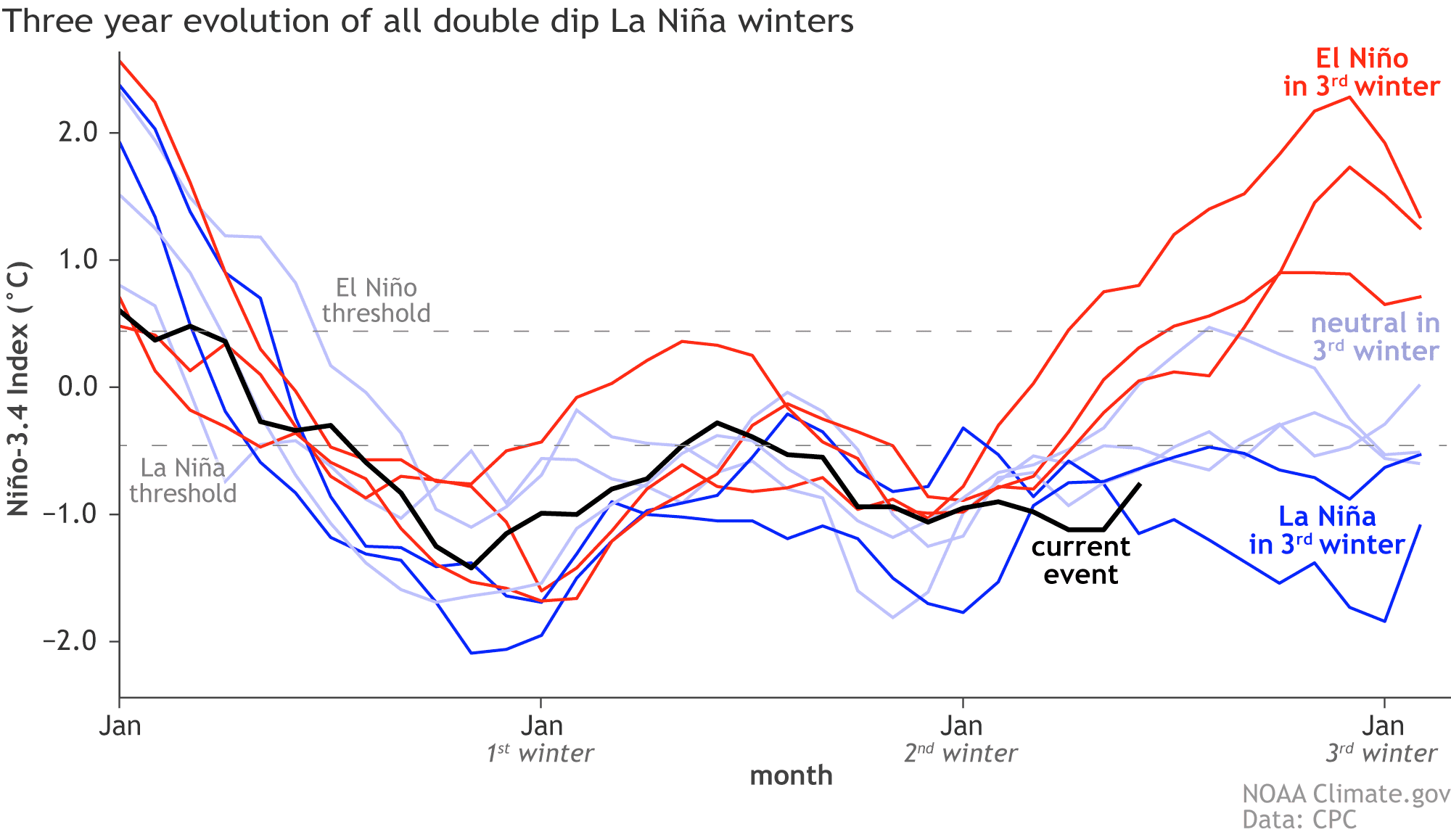

Given all these sources of confidence, why isn’t the probability of La Niña higher? First, while a majority of the climate models do predict continued La Niña, there is still a pretty wide range of potential outcomes. Also, as I mentioned above, the subsurface temperature in the eastern half of the tropical Pacific is a bit warmer than average. If this anomaly is large—much cooler than average, or much warmer—it has a stronger relationship with the eventual Niño-3.4 index. However, when it is pretty small, as it was in June 2022, the outcomes are more varied. Finally, as we’ve covered extensively, a triple-dip (three-peat!) La Niña is a pretty unusual occurrence.

That’s all, folks! I’m going to go dip my toes in the Pacific.

This post first appeared on the climate.gov ENSO Blog and was written by Emily Becker.