Chances are, if you’ve gone backcountry skiing in the United States recently, you’ve looked at an avalanche center forecast. Regional avalanche centers utilize a mix of professional observers and forecasters, public observations, and weather stations to generate daily assessments and forecasts of the avalanche risk in mountain ranges across the United States. Looming federal budget cuts have forced the Forest Service to institute a hiring freeze this fall for seasonal employees right as many avalanche centers are getting ready to bring on their winter workforce of experts. Though several strategies are being pursued to help mitigate the impacts of this hiring freeze, avalanche centers may not be able to provide the same level of operations this winter that the public is used to.

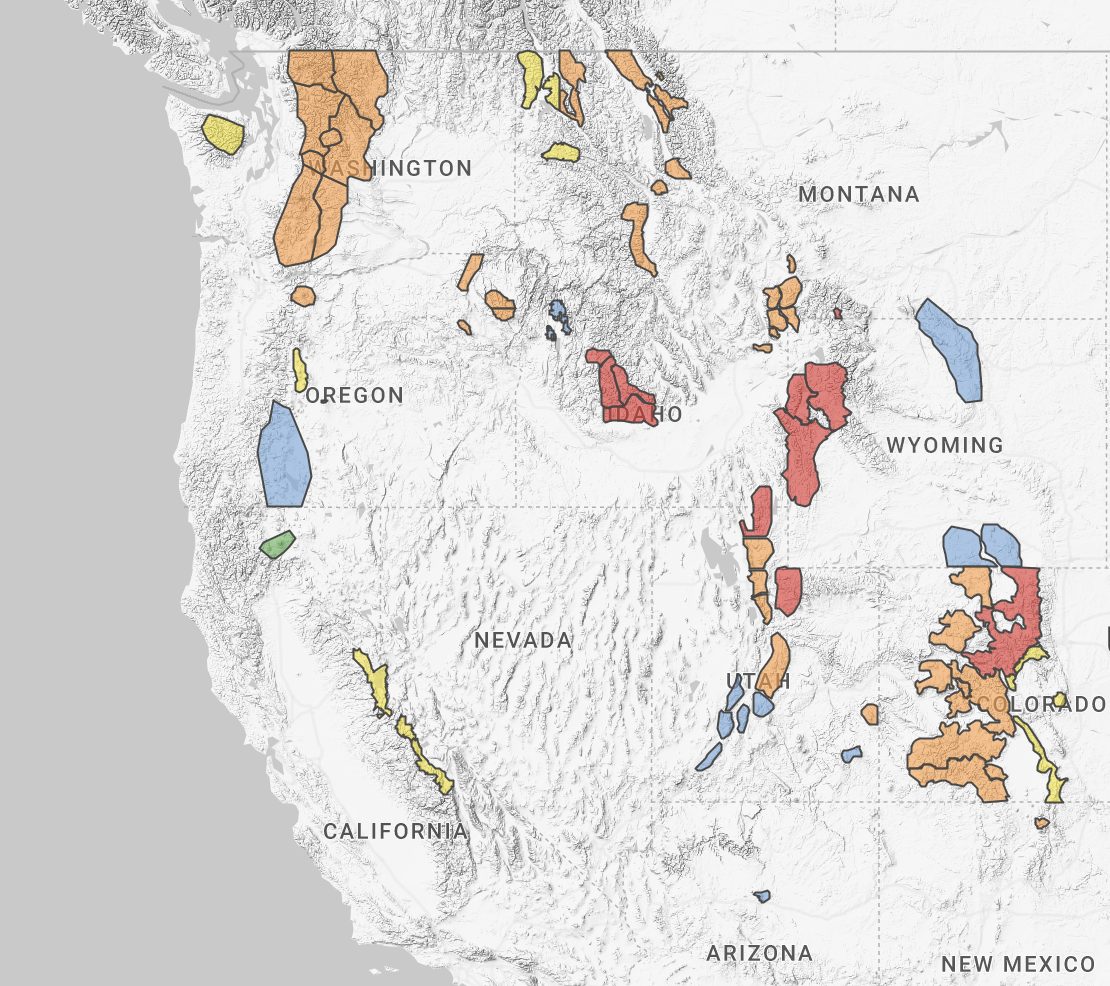

There are 24 backcountry avalanche centers distributed across the United States, 14 of which are operated by the Forest Service. These avalanche centers primarily provide avalanche forecasts to the general public free of charge in addition to public education and outreach. Most avalanche centers rely on a mix of public funding from the Forest Service, donations to nonprofits supporting avalanche centers, and corporate sponsorships to operate each winter. Jayne Nolan, Executive Director of the American Avalanche Association, described in an email how every avalanche center is a public-private partnership with a local nonprofit. On average, the nonprofit group provides half the funding for the avalanche center. The majority of the Forest Service funding goes to paying the wages of field technicians. These avalanche professionals detailed information about the snowpack and its stability and work with avalanche forecasters to compile data from field observations and public observations to assemble the daily avalanche forecast. Outside of avalanche forecasting, Forest Service employees also investigate avalanche accidents and fatalities to inform the public about what caused an avalanche and offer guidance on how the outcomes could have been mitigated. With a seasonal hiring freeze in place, none of these critical positions can be filled.

In addition to daily forecasts, avalanche centers provide the public with a thorough analysis of accidents as well as the snowpack conditions and travel decisions that contributed to them. This work is on top of the regular forecasting duties of the avalanche center and is an example of some of the operational capabilities that may be lost with restricted budgets and workforce. As an example, the Utah Avalanche Center did a thorough investigation of the Wilson Glade Avalanche, which killed four people in Millcreek Canyon, Utah, in February 2021. Their analysis included tour details for the two groups involved in the avalanche, rescue efforts on-scene, analysis of the terrain in the start zone and avalanche path, weather data leading up to the accident, and snow pit profiles directly from the crown of the avalanche. These data provide a clear picture of how this tragic accident occurred, as well as how similar accidents may be avoided in the future. In putting together this investigation, accident survivors were interviewed and several avalanche center personnel traveled to the avalanche site to collect terrain and snowpack data. With a workforce potentially stretched thin by Forest Service hiring freezes this winter, investigations of this magnitude and depth will be some of the programs most threatened by short-staffing and restricted budgets.

The first inklings of a budget crisis for the Forest Service came on May 16, 2024, at a meeting of the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. Randy Moore, Chief of the Forest Service, was questioned by Senator Joe Manchin, Senator John Barrasso, and other members of the committee on why timber harvesting and wildfire fuel reduction projects have been reduced despite a growing budget for the Forest Service. Many committee members brought up concerns over closing sawmills in their states because of a lack of harvested timber from public lands and a few openly suggested a significant reduction in the Forest Service budget. Later, on September 17, 2024, Chief Moore announced on an all-hands call that seasonal hiring freezes would be put in place to prepare for a “budget-limited environment.” What do timber harvesting and sawmills have to do with avalanche center operations this winter? Nothing, but that is part of the problem avalanche centers are trying to work through.

Though avalanche centers provide an important public service, they are a tiny part of the Forest Service. One Forest Service employee involved with the avalanche program who wished to be unnamed because of the politicized nature of the budget situation described how many higher-ups in the Forest Service have not even heard of avalanche centers before, and are not aware of the specialized nature of their work. Politicization of the budget situation has complicated problem solving and solution seeking, leading to more conflict within the Forest Service. Many other seasonal employees in the Forest Service work on projects that can be delayed or reduced in scale, but avalanche centers do not have the same wiggle room. Nolan told SnowBrains in an email that “any loss in appropriations directly affects operations.” Since the announcement of the seasonal hiring freeze, people both inside the Forest Service and in partner groups like the American Avalanche Association have been working to secure exemptions to allow for the hiring of seasonal avalanche center staff. On the September 17 all-hands call, Chief Moore recognized that fewer employees would translate to less work getting done, but he encouraged members of the Forest Service to do “what you can with what you have.” However, avalanche program employees within the Forest Service and partner groups like the American Avalanche Association are concerned that without exemptions to the hiring freeze for avalanche forecasters, “doing what you can with what you have” may look like no forecasting without forecasters.

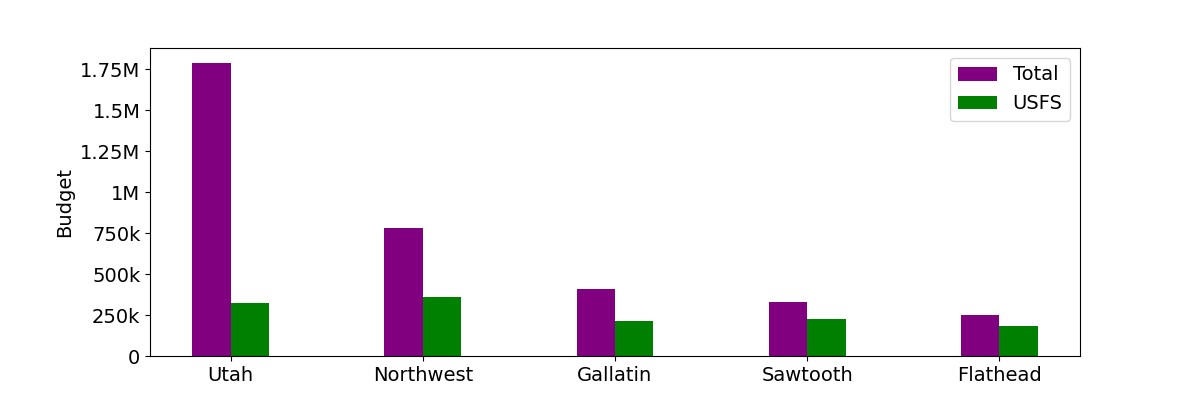

“Nonprofit partner groups have enabled Forest Service avalanche centers to expand staff and programming for their regions and communities by providing additional funding and resources,” Nolan said. According to annual reports from several different avalanche centers, the Forest Service pays for the bulk of forecaster wages and operational expenses. In smaller avalanche centers like the Sawtooth Avalanche Center in Idaho or the Flathead Avalanche Center in Montana, Forest Service dollars make up more than half the budget. On the other end of the scale, public funding accounted for less than 20% of the Utah Avalanche Center budget, which was more than five times larger than the Sawtooth Avalanche Center Budget. Below is a chart showing the total budget of five different avalanche centers along with the contribution from the Forest Service.

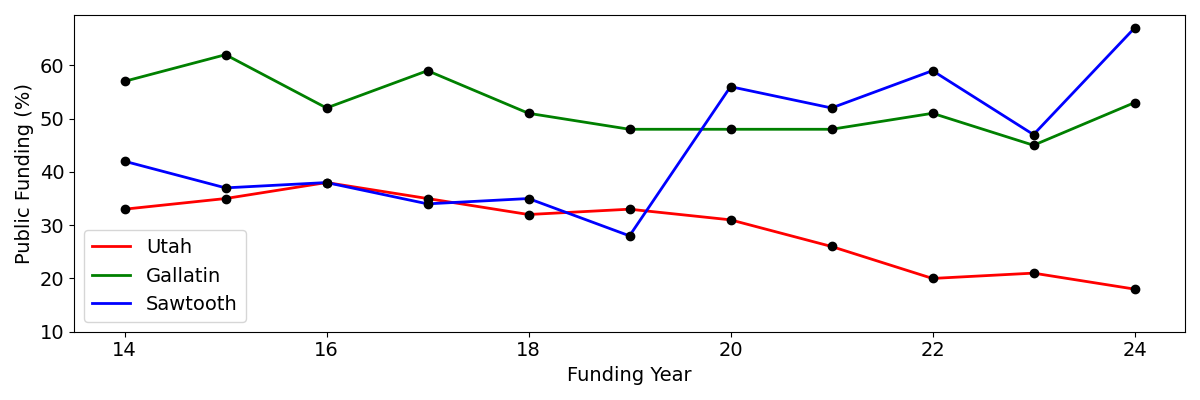

Forest Service funds typically cover pay for forecasters and some equipment costs, with nonprofits typically picking up the other items in the budget like education and outreach. In many cases, nonprofit partners also contribute to forecaster wages. While the Forest Service budget and their contribution to each avalanche center varies from year to year, nonprofit funds can often fluctuate quite a bit more, based on how successful fundraising campaigns are. Thus, the total share of an avalanche center’s budget that comes from the Forest Service can fluctuate over time. The graph below shows the public funding share of the expenses for three different avalanche centers, based on financial information in their annual reports. The Utah Avalanche Center has steadily decreased its reliance on the Forest Service for funding over the last ten years. Prior to 2020, the Sawtooth Avalanche Center was following a similar trajectory, but between 2019 and 2020 money from the Forest Service substantially increased along with its overall budget. In many cases, Forest Service funds are matched dollar for dollar with money from the community and in some cases, Forest Service funds are more than quadrupled.

Even though avalanche centers benefit a great deal from community support and nonprofit funding, avalanche forecasters are still Forest Service employees and are subject to Forest Service hiring rules. While it should be easy to obtain exemptions to the seasonal hiring freeze for positions that are not paid out of the Forest Service coffers, exemptions still are tricky to obtain and take time, especially when many of the people with the power to grant exemptions are not aware of the avalanche program within the Forest Service. Yet, progress is being made. The same unnamed Forest Service employee I spoke to for this story said that exemptions have been obtained for a majority of the seasonal forecaster positions and that efforts are underway to secure the rest of the seasonal positions for the upcoming season.

What is clear from the tremendous levels of community funding across the United States is that the backcountry skiing community places an extremely high value on their avalanche centers. These small operations, which provide life-saving forecasts and information, may not be a significant part of Forest Service operations on a national scale, but they have been swept up in a national budget crisis and are now looking at one of the most uncertain starts to the season in memory. Advocacy efforts from within the Forest Service and from partner groups will determine if avalanche centers have the staff they need to operate at the level the public has come to expect. The first facets of the season are already growing. The coming weeks will determine if there will be enough forecasters to find them.

More from Zach Armstrong:

- The Battle Over The Future Of Palisades Tahoe

- How the Fatal GS Bowl Avalanche at Palisades Tahoe, CA, Happened and Why it Could Happen Again

- Public Money Gets Funneled into Massive Deer Valley, UT, Expansion

- Inside the Ski Industry’s Post-Pandemic Boom

- How Eldora, CO, Ski Patrollers Finally Got Their Union

One thought on “Forest Service Budget Challenges Threaten Avalanche Center Operations Nationwide”