As we previously reported, a local man died after being caught in an avalanche around 1:00 pm Sunday, March 15 in Idaho. The man was around 60-years-old and was skiing in the out of boundaries area near the Pebble Creek Ski Area. The avalanche that killed him was about 300 yards and six feet deep. Ski patrol dug the man out and CPR was performed on him for about 45 minutes. He was irresponsive and was pronounced dead around 4:00 pm.

The avalanche danger near Pebble Creek Ski Area at that time was high and local officials were asking people to stay out of areas that are out of bounds and to use precaution when navigating avalanche terrain.

There have been 27 avalanche related fatalities in North America this season. 19 in the USA this season, and 8 in Canada.

Below is the full report from the CAIC, posted in full as a learning experience for all of us.

Avalanche Details

- Location: North of Skyline Peak

- State: Idaho

- Date: 2020/03/15

- Time: 1:00 PM (Estimated)

- Summary Description: 2 sidecountry riders caught, 1 partially buried, 1 buried and killed

- Primary Activity: Sidecountry Rider

- Primary Travel Mode: Ski

- Location Setting: Accessed BC from Ski Area

Number:

- Caught: 1

- Partially Buried, Non-Critical: 0

- Partially Buried, Critical: 0

- Fully Buried: 1

- Injured: 0

- Killed: 1

Avalanche:

- Type: SS

- Trigger: AS – Skier

- Trigger (subcode): u – An unintentional release

- Size – Relative to Path: R3

- Size – Destructive Force: D2

- Sliding Surface: O – Within Old Snow

Site

- Slope Aspect: NW

- Site Elevation: 8066 ft

- Slope Angle: 40 °

- Slope Characteristic: —

Avalanche Comments

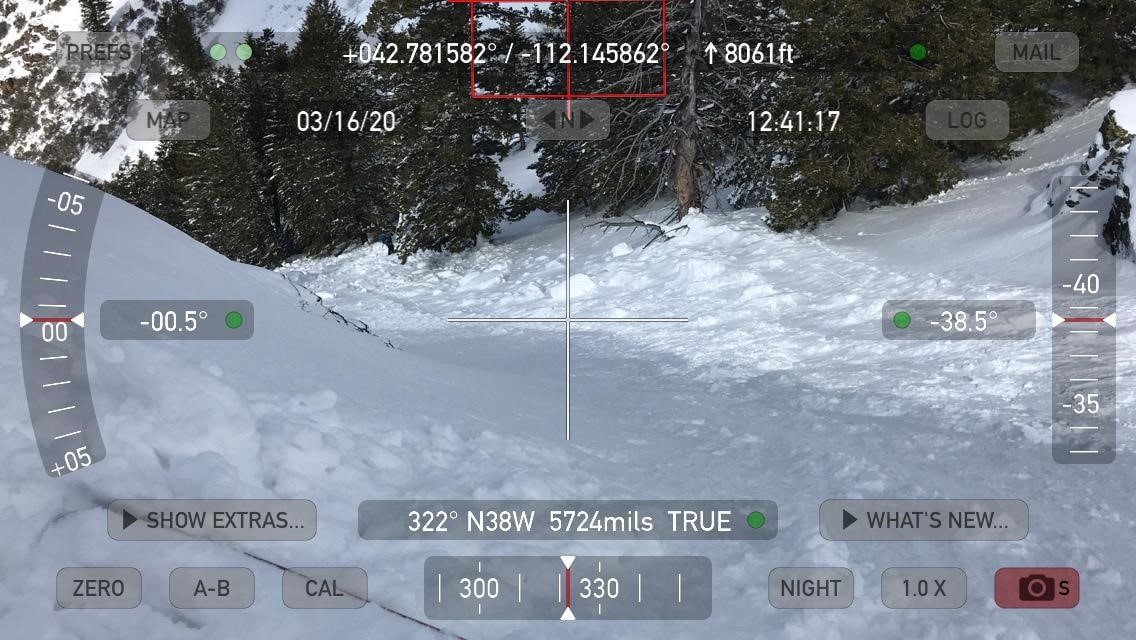

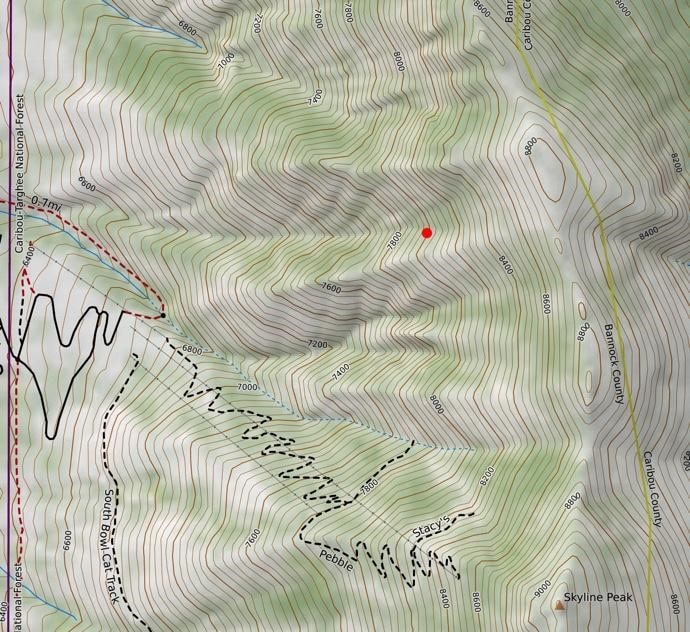

The avalanche occurred in an avalanche path known as ‘First Scary Monster’, a corniced slope entering ‘Canal Street’ on the north side of a prominent sub-ridge in the upper part of the Green Canyon drainage (Figure 1). With a large fetch consisting of a broad open slope to the south and sustained southerly winds in the previous 36 hours, deep wind drifts formed on the concave slope on the northern side of the sub-ridge.

The wind slab avalanche is classified as SS-ASu-D2-O. It released on a north-northwest facing slope at 8070 feet in elevation, fractured 1 to 3 feet deep and approximately 180 feet wide, and ran approximately 400 vertical feet through a moderately forested slope. The slope angle was 39 to 40 degrees at the crown (Figures 2 [above] and 3). The slope angle gradually decreased below the start zone. The debris averaged 2-4 feet deep but piled up deeper on the uphill side of trees (Figure 5 below). The victim was buried about 130 vertical feet below the crown on the uphill side of a tree with his arm wrapped around it (Figure 4 below). The surviving skier was partially buried about 50 feet below and in the same fall line as the victim. According to Pebble Creek Ski Area staff, this avalanche was larger than any slide in that avalanche path in many years.

Weather Summary

Heavy snow started falling in the Portneuf Range on March 14, and it was drifted by sustained south winds. The nearby Sedgwick Peak SNOTEL site at 7850 feet reported 2.3 inches of Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) in the 36 hours previous to the accident. On the day of the accident, Pebble Creek Ski Area reported 20 inches of new snow from the storm. Light snowfall continued to fall on the morning of March 15. The ski area reported south-southwest winds blowing 10 to 15 mph in their morning weather reports on both March 14 and March 15.

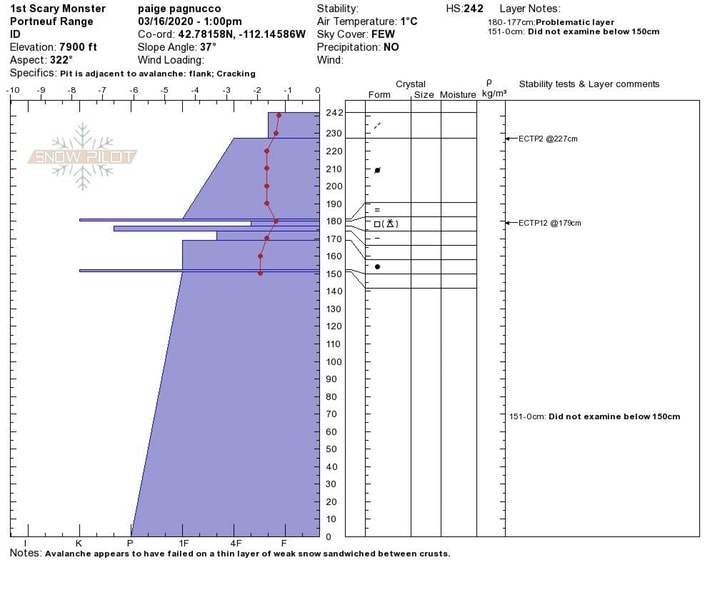

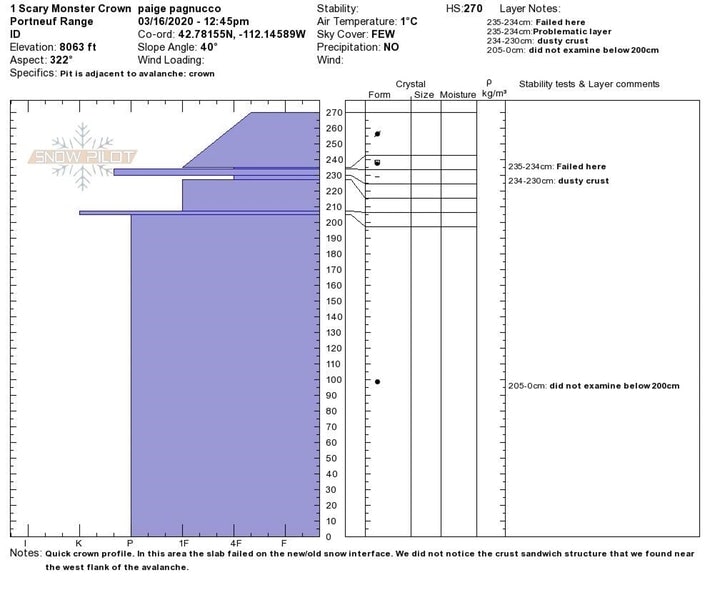

The slab avalanche involved wind-drifted snow that appears to have failed on a thin layer of small-grained faceted snow and graupel sandwiched between crusts. The weak snow and crusts were likely formed/deposited during fair weather in early March and were located immediately below the March 14-15 storm snow (Figure 8). An extended column test (ECT) performed the day following the avalanche near the western side of the slide yielded unstable results (ECTP 12). The thin crust on top of the facets and graupel was not apparent at the avalanche crown; there, the avalanche appeared to fail on facets and graupel overlying a crust (Figure 9).

Accident Summary

On 3-15-2020 around 1:00 PM, a party of four skiers crossed a rope line marking the northern boundary of Pebble Creek Ski Area and entered the backcountry (Figures 6 and 7). The group were longtime Pebble Creek skiers. They rode chair lifts up the mountain before legally entering the backcountry terrain outside the ski area boundary. The skiers traversed into the ‘Canal Street’ area north of the ski area boundary. They were familiar with the terrain and had skied there in the past. None of the party carried avalanche rescue gear. Two of the skiers were on the wind-drifted slope when one or both triggered a slab avalanche. Both were caught and carried down the steep slope through trees.

One skier was partially buried and was able to free himself from the debris. He and other members of his party then found their buried partner under about three feet of snow on the uphill side of a tree. They extricated the victim approximately 15-20 minutes after the avalanche released. CPR was initiated at the burial site by bystander medical professionals. Pebble Creek Ski Area staff was notified and quickly responded to the accident site. Despite valiant rescue and resuscitation efforts, the victim was unable to be revived.

Comments

All of the fatal avalanche accidents we investigate are tragic events. We do our best to describe each one to help both the people involved and the community as a whole to better understand them. We offer these comments in the hope that it will help people avoid future avalanche accidents. We do not intend to place blame on any of the involved parties or imply that any particular action or decision would have prevented this tragic event.

* Proximity to a ski area: Commonly called “sidecountry”, the terrain accessed by leaving a ski area is the backcountry, despite its proximity to in-bounds terrain. Recognize when you cross a ski area boundary, avalanche mitigation work is not performed and you are responsible for making snow stability decisions and performing your own rescue. Lift-served skiers who exit ski areas to play on surrounding slopes are often lulled into a false sense of security due to their comfort and familiarity with the nearby terrain. Although the steep slopes adjacent to ski areas are easily accessible, they typically pose a much greater risk of avalanches – especially immediately following significant storms – than slopes within ski areas.

* Consequences: The avalanche carried the skiers into a forested area, dramatically increasing the chances of striking a tree at high speeds and being injured or killed by trauma. If there’s a chance a given slope could slide, recreationists should consider the consequences of an avalanche before skiing or riding the slope.

* Rescue gear: When traveling in avalanche terrain, everyone should have essential avalanche rescue equipment: carry an avalanche transceiver (beacon), shovel, and probe and know how to use them.

* Safe travel techniques: All users are encouraged to attend an avalanche awareness class or more advanced training to learn safe travel techniques. Crossing steep slopes one at a time while the rest of your party watches from a safe area prevents multiple people from being involved in avalanches, increasing the chances of a successful rescue.

This report is a product of a cooperative effort between the USFS Utah Avalanche Center, USFS Sawtooth Avalanche Center, and Caribou-Targhee National Forest. The Pebble Creek Ski Area provided additional information and access to the accident site. This report was produced by Paige Pagnucco and Toby Weed of the Utah Avalanche Center (Logan Zone) who visited the site on March 16, 2020

What app are those slope angle pics from?