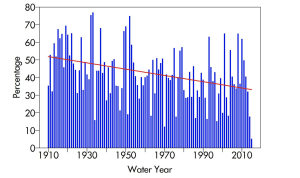

While the Eastern Seaboard has broken numerous records for water and precipitation over the past few years, the West has taken a much drier and warmer pattern. Since 2000, the Mountain West still sees a good year here and there—even a record snowy one. Yet, the trend for precipitation over the last 22 years has largely pointed downwards from the 140-year average. As of spring 2022, the Western US hit the record for the worst megadrought since 800 CE.

Considering a climate change-stricken future, skiers and boarders have to reckon with the idea of having less snowpack to work with. Not only will mountains likely receive less snow, but the snow they do receive might be wetter and warmer. Higher average winter temperatures can turn what would be snow into rain or sleet. Additionally, warmer high-elevation air temperatures can lessen the positive effects of orographic lift and lead to no precipitation at all.

The effects of this can reach much further than just skiers, though. Major agricultural areas might have to deal with less water throughout the year due to faster snowmelt. The San Joaquin Valley is already experiencing the brunt of these consequences. Even with a heavy snow year, higher spring temperatures will release the water too quickly for maximum retention. Reservoirs around the Sierras lose the water to run off before it can be used. This requires farms to draw from quickly depleting underground aquifers. Furthermore, rangelands throughout the Rockies are facing raging wildfires and crippling drought, severely impacting the cattle industry. Grasses show up earlier but are often killed by residual Spring frosts. Forage is weaker and thinner from a lack of water, leading many ranchers to supplement larger portions of their cattle with packaged feed.

Additionally, warmer temperatures and earlier spring snowmelt cause summer wildfires to start earlier and last for longer. Historically, spring snowmelt water lasted through mid to late summer. The melt held the worst fires at bay by retaining a higher moisture content in the soil while air temperatures warmed. Now, even with the highest precipitation years, fires can cause detriment to the ski industry, residential areas, and agricultural areas as early as June.

While a warming climate might suggest that atmospheric river events will transport more moisture per event, the consistency of water/snow supply around the West will suffer. While the general pattern suggests that the West will see drier summers from rising temperatures and lower relative humidities, climate scientists speculate that atmospheric river systems may actually increase in strength when they do happen. This may seem like good news, but the frequency and consistency that these storms happening will likely decrease. Dry soil doesn’t soak up water nearly as efficiently as moist soil, so much of the rain or snow that does precipitate will be lost to runoff.