This is the second article in a two-part series discussing what makes great powder and the reasons why it is found in the Cottonwood Canyons near Salt Lake City, Utah. Part 1 sets the stage and presents the facts for why Utah has some of the best powder skiing in the world. Part 2 is for the weather nerds and describes why the Cottonwood Canyons are the perfect setup for amazing snow conditions year-in and year-out.

For more learning about weather check out the National Weather Service’s online learning portal “The Jetstream“.

Big Cottonwood Canyon (Brighton and Solitude) and Little Cottonwood Canyon (Alta and Snowbird) resorts are world-renowned ski destinations and Utah is said to have the “Greatest Snow on Earth”.

At first this may seem odd and, frankly, a bold statement for a state probably better known for desert towers and slot canyons.

So let’s explore what it is about the weather that makes Utah powder so magical!

To understand what makes the Cottonwood Canyons a hot spot of snowfall, we need to start with the basics ingredients of what makes a snow storm (moisture, cold air, and energy). Once we have the background, then we will get into the local factors that enhance the snowfall across the Wasatch Mountains.

The Basics – 3 parts every potent snow storm must have.

Moisture is the amount of water vapor stored in the air mass. This is measured as precipitable water, shortened to PWAT, which is how much water can be condensed out of the air. This is reported as a depth of water, such as “PWAT values are between 0.5 and 0.6 inches”. Worth noting is that warm air can hold more moisture than cold air, so it is often the warm tropical air masses that have the big PWAT values greater than a few tenths of an inch.

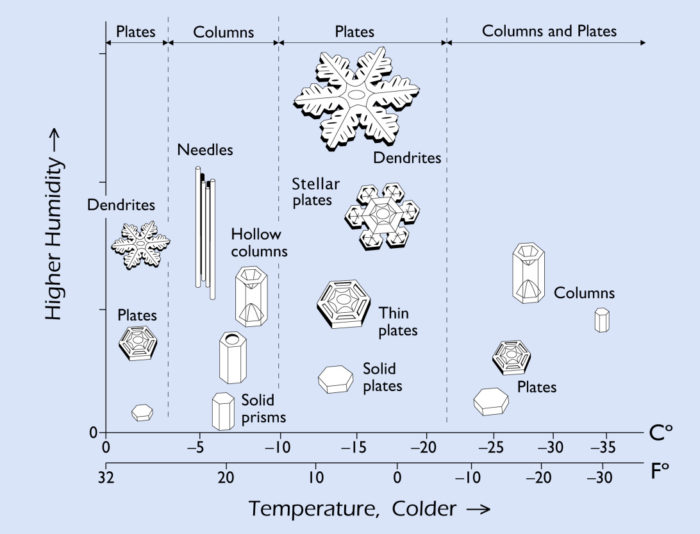

Cold air is a somewhat obvious ingredient in that you need to freeze the water vapor to get snow, but there is actually more to it than just “below 32 degrees”. The temperature and amount of water vapor dictate the type of snow crystal that forms. The type of snow crystal dictates how tightly the snowflakes pack together and ultimately how dense the powder ends up being. As discussed in Part 1, snow density is an important factor of great snow. As it turns out, it is the stellar dendrites which produce the super light snow also known as “cold smoke”.

And the last ingredient is Storm Energy. Energy provides the means to mix the cold dry air and the warm moist air together to make it all happen. The energy can come in as wind or convection (warm air rising up into colder air) which mixes all the ingredients together.

The Cottonwood Canyons Magic

So now that we know we need moisture, cold air, and energy to get any kind of a snowstorm, why do the Cottonwood Canyons get so much snow?

Orographic Enhancement. While having high elevation terrain certainly helps to collect snow, it is the change in elevation from the relatively low valleys to the high peaks over a short distance which really squeezes out the snowfall. When the relatively warm moist air at low altitudes slams into the sides of the peaks, it is forced up into the colder upper altitude air and the snow starts to fall. In fact, annual snowfall in the Wasatch increases roughly 100″ for each 1000′ of elevation gain.

Convection. In addition to the mountains physically forcing warm moist air up into colder air, convective cells can form further mixing the moisture and cold air. This so-called convective orographic enhancement is driven by buoyant instability where, much like a bubble underwater, a low altitude air mass becomes less dense and shoots up into the upper portions of the atmosphere. This really gets the mixing of moisture and cold air going, producing the high precipitation rates needed for those mega 24-hour storms. The Wastach seems to get a lot of these convective storms, meaning a lot of big storms.

Location, Location, Location. The broad high terrain of the Central Wasatch sticks out of the terrain like a big snow-ning rod. The mountains are exposed to storm flow from all different directions. What this means is that many different storm tracks impact the range and get the orographic enhancement going. The more often it snows, the more snow is going to fall.

Terrain Shape. If you look at the upper portions of the Cottonwood Canyons, especially from the northwest, there is a competent ridge that blocks flow. As the moist air flows over the range the only way out is up through the cold air. There is not a lot of moisture that can escape by flowing around the mountains. The northwest flow is particularly good for upper Little Cottonwood Canyon, which can sometimes get double the amount of snow as elsewhere in the range under these conditions.

Storm Patterns. Winter season atmospheric flows just happen to hit the Wasatch Range just right. It is often the case that storms hitting the Cottonwood Canyons often start off with warm moist air flowing in from the southwest followed by cold dry air coming from the north. This pattern for one gets brings lots of moisture and cold air to the same location, but also very frequently results in a “right side up” structure with warmer dense snow below cold dry snow on top. After the front (the boundary between the warm and cold air) passes over often the Cottonwoods are left in an unstable air mass with very low winds. The orographic effects keep the snow falling and the cold air temperatures produce classic dendrite snowflakes. The combination adds up to a super low-density topping of powder at the end of the storm.

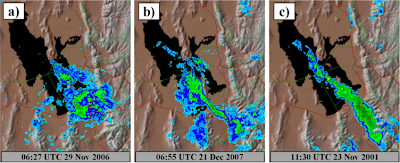

Lake Effect. Now I saved this factor for last, because there are some misconceptions about the fabled Great Salt Lake effect and how much of an influence it really is to Utah powder. First of all, lake effect mostly enhances snowfall by increasing lift and helping flow converge to create focused bands of heavy precipitation (not adding substantial amounts of heat and moisture like the Great Lakes effect in the upper midwest). So yes, the Great Salt Lake effect is real. Sometimes up to a foot of snow can fall in isolated locations in Salt Lake Valley due to lake effect. And if lake effect snow bands make it to the mountains and are orographically enhanced, those storms can pack a punch, dropping multiple feet of snow over a short period. But this weather anomaly does not contribute greatly to the overall total snow depth. University of Utah meteorologist Jim Steenburgh suggests that as little as 5% of the total annual snowfall in the Central Wasatch can be attributed to lake effect snow.

While every winter storm is made of three main ingredients (moisture, cold air, and energy) the Wasatch Mountains of Utah have a few extra factors that boost the snowfall totals. A large elevation change drives orographic and convective instability, further mixing the moisture with cold air. The mountains are arranged in such a way that storms coming from many different directions run into the highest peaks. Storm flow from the northwest is funneled and milked dry in the upper Cottonwood Canyons. Large scale storm patterns deliver both deep moisture and cold dry air and the storm evolution often leaves perfect dry powder as a last parting gift. And the nearby Great Salt Lake will occasionally help the skies open up and drop feet of snow on the mountains.

Sure, there are other places that have a few of these factors. But to have them all together in one place is pretty magical.

Honestly, I would have to say that it does make a strong case for the “Greatest Snow on Earth”!

For more technical information, weather musings, and powder snobbery check out Jim Steenburgh’s book “Secrets to the Greatest Snow on Earth: Weather, Climate Change, and Finding Deep Powder in Utah’s Wasatch Mountains and Around the World” and his blog Wasatch Weather Weenies. They are great sources of knowledge and also very amusing. Much of the author’s knowledge of weather and Wasatch phenomena was fortified by Jim’s works.